At Hornby Hobbies, close attention to engineering details and a top-down approach to design help the company’s designers bring to market toys and collectibles that have enormous appeal for young and old alike

For many people, pandemic-related lockdowns have been an opportunity to spend more time on the hobbies they enjoy, to return to hobbies remembered fondly from childhood, or to take up new hobbies entirely.

That’s been good news for Hornby Hobbies, the British-based maker of toys and collectibles, which has seen a big jump in sales over the past year or so. As Hornby chief executive Lyndon Davies recently told the BBC: “When there are problems in the world, people do turn inwards, they do look for things of comfort, and in a hobby, they find comfort.”

The Hornby name may most commonly be associated with the iconic model railway brand, but the company is also home to other well-known products, including Airfix scale model kits and the Scalextric line of track-based slot car racing sets. Across the entire portfolio, there’s a big drive now to capitalise on the recent sales surge and to keep broadening the appeal of its products to address the widest possible audience, says Hornby Hobbies’ head of strategic delivery, Jamie Buchanan.

New product investment continues to grow, he says, and the company, which celebrated its centenary in 2020, is developing significantly more new releases and ranges each year. At the same time, it is increasingly looking to incorporate digital technologies into what might otherwise be seen as fairly traditional toys.

For example, this combination of the physical with the digital has seen Bluetooth circuit and accessory controllers developed for Hornby trains, so that customers can control their model trains and railway layouts from their smartphones. Similarly, Scalextric Sparkplug, launched in 2020, is a wireless app-controlled system for controlling cars on the track from Android and iOS devices.

“Technology has been a driving force in all sorts of purchases for kids for some years now, with your iPads and your smart devices and so on – but for many parents and grandparents, aunties and uncles, there’s a frustration and concern that too much of kids’ time is sat in front of screens and that traditional forms of play and the benefits these bring are getting neglected as a result,” Buchanan observes.

“While everyone appreciates that screens are not going to go away, we think that Hornby is in a great position to combine traditional and modern play in ways that have cross-generational appeal.”

The company’s efforts are already starting to pay off, he adds. “What we’re starting to see – as we hoped we would – is that older family members and kids are coming together to enjoy these products, because the kids have an affinity with the digital aspects and the adults enjoy the traditional nature of the products themselves. You get a really nice synergy there.”

Authentic experiences

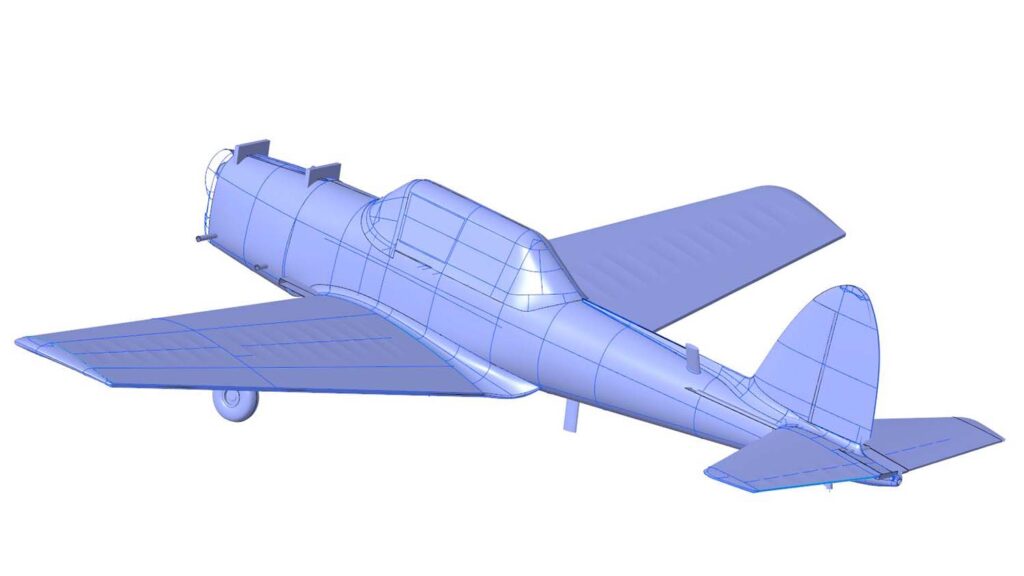

Product accuracy is a big deal for eagle-eyed and clued-up Hornby enthusiasts. They expect absolute authenticity, whether they’re looking to race the Scalextric version of the 2007 Vodafone McLaren Mercedes driven by Lewis Hamilton in his debut Formula 1 season, or build a 1:48 scale model of the de Havilland Chipmunk T.10 pilot training aircraft, using the kit released this summer.

So before product designers get to work in PTC Creo, the company’s CAD system of choice, a considerable amount of detective work has to happen first. This involves full-time researchers poring over original manufacturer drawings, tracking down images in photographic archives, visiting museums that have a particular aircraft or locomotive on display, and speaking with historians and other experts.

We’re starting to see older family members and kids coming together to enjoy these products Jamie Buchanan, Hornby Hobbies

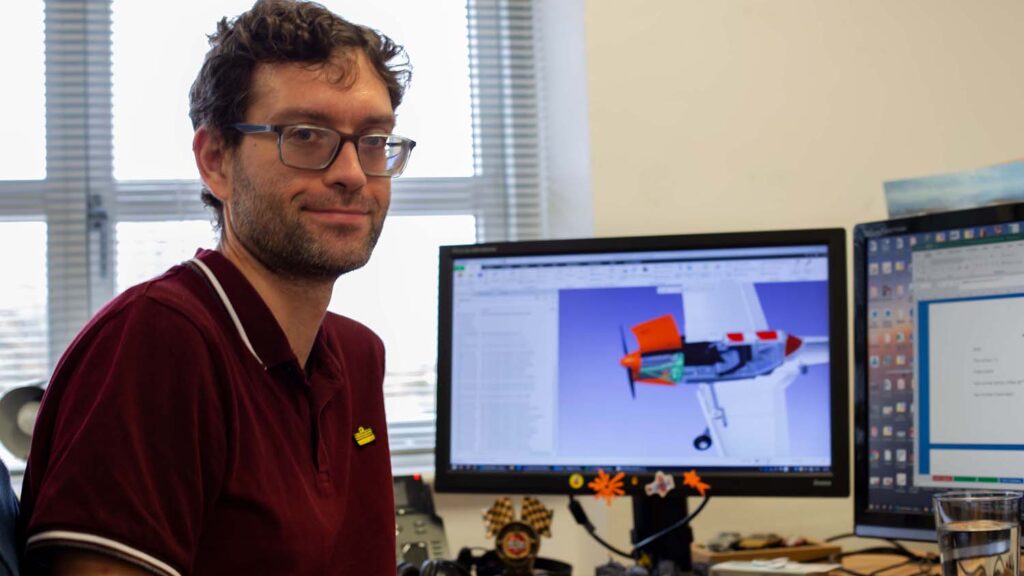

Since 2015, 3D scanning has become an increasingly important part of the mix, says Matt Whiting, design manager on the Airfix team. “3D scanning is a great way for us to capture the external – and to a limited extent, internal – shapes and features of the subject matter, so we’re coming to rely on it more and more.” While Hornby has typically relied on third-party experts to carry out this work, he says, it is increasingly bringing this capability in-house.

All along the way, the researchers are on hand to assist the product designers in their work, because it can be a real minefield to accurately replicate vehicles that are in many cases historical artefacts in 3D CAD, says Whiting. “We have to be 100% sure we know what we’re looking at and 100% confident of what we need to create in Creo, so we don’t transfer into our design mistakes that were made in the restoration or repair of a real-life vehicle, for example, or the misinterpretation of a drawing.”

Hornby Hobbies – Top-down design

While acute attention to engineering detail is what brings final products to life for customers, the way designers work on any product across the Hornby Hobbies portfolio is roughly the same, says Jamie Buchanan. In short, whether they’re developing products for Airfix, Scalextric, Hornby, or any other company brand, the company’s product designers generally follow the top-down methodology supported by Creo. The company has used PTC’s technology since 1994 and has been supported throughout by Cambridge-based Root Solutions, PTC’s longest standing Platinum Partner in the UK.

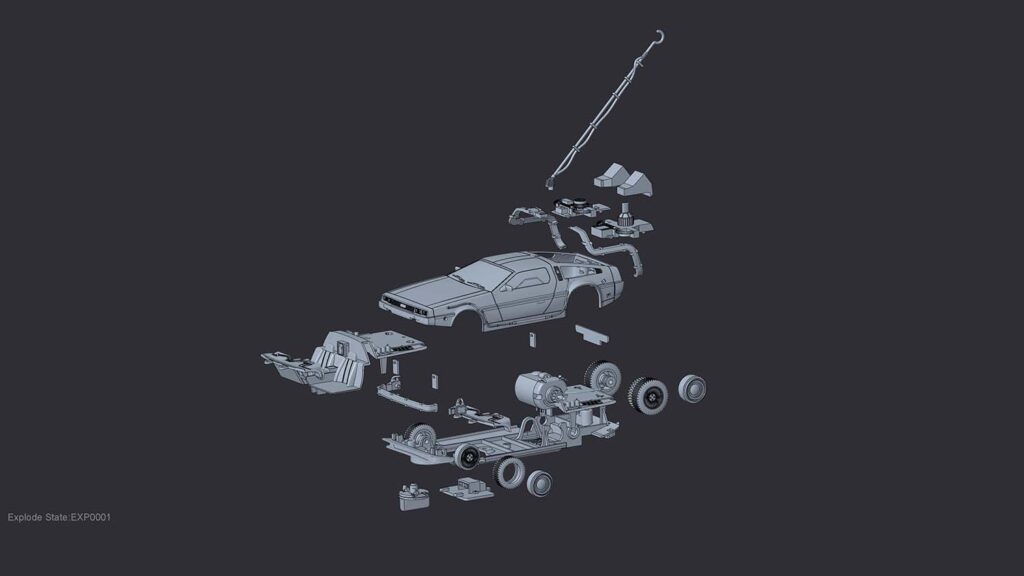

This adherence to top-down design is interesting, given the considerable difference between, say, a Scalextric car that is manufactured and arrives with the customer ready to race and an Airfix model that the customer will potentially spend many happy hours assembling themselves. But the top-down methodology, says Buchanan, works well in terms of reflecting the vast number of products in the company’s portfolio, respecting the similarities (and differences) that exist between them, and supporting the complex interdependencies between their individual components.

As Whiting explains: “All of the geometry that we need to develop that refers to more than one part will be developed into a skeleton model. And then that’s referenced down into the individual part file, so that if we change something in the top-level model, that change filters down into the child models.”

This is important, because products are regularly rested (in other words, temporarily withdrawn from the market) and then re-released, and it’s vital that designers new to a particular product are able to understand the design intent and history behind it.

“So, with Airfix, one of our most popular subjects is the Supermarine Spitfire, a 1940s British fighter plane. It’s incredibly popular and, as a result, we’ve probably released a new Spitfire kit every year for about the last 10 years,” Whiting explains. “And all of our Spitfire kits go back to one skeleton model, which I developed in Creo a number of years ago. I based it on the original Supermarine lofting drawings and converted all of the offset tables into a set of Creo surfaces that replicate the incredibly evocative shape of the Spitfire. So that base, that skeleton model, has been scaled up and scaled down, with bits chopped off and bits added on to it for different products – but the basic surfaces have gone into probably 10 to 15 different products, which a really nice way of achieving accuracy and getting better value for money out of the work that we do.”

With offset tables and point cloud meshes imported into Creo, he and his colleagues get to work on scaling it down, manipulating it and generally assembling a suitable data set to use for a product.

“From there, we can then reskin it. For a lot of our work, because of the shapes of the objects we focus on – sports cars, aircraft, ships – we rely quite heavily on the ISDX module within Creo, which allows us to robustly capture 3D shapes to develop them into a skeleton model.”

Here, he’s referring to the Creo Interactive Surface Design Extension (ISDX), which gives the team tools that help them manipulate curves and surfaces to achieve the sleek aesthetics of the iconic vehicles they’re recreating.

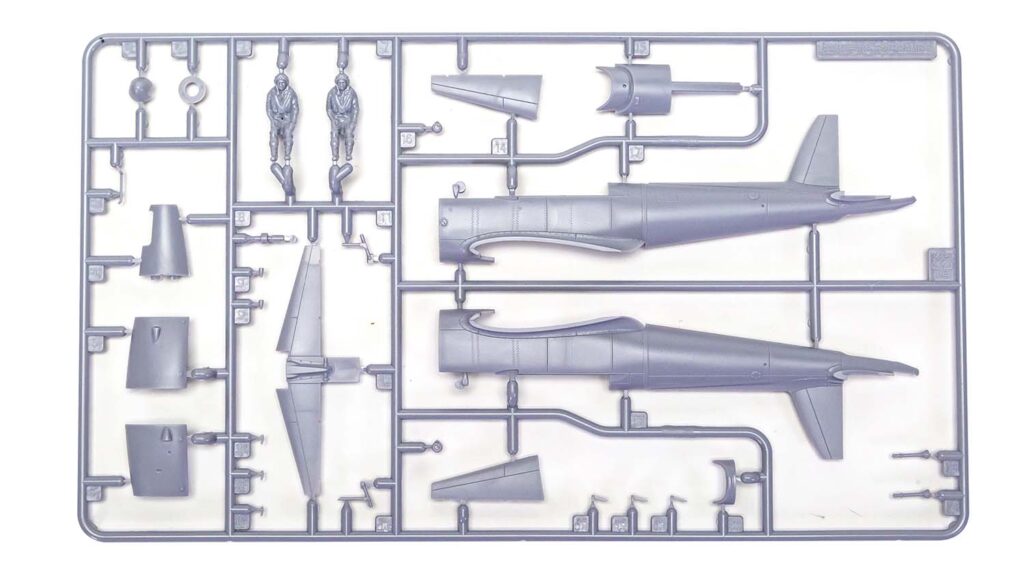

In the case of Airfix, parts are designed to be injection moulded and presented to the customer as a collection of snap-out parts arranged on a runner. The job of deciding how individual parts are arranged on that runner falls to specialist third-party toolmakers, says Whiting, but his team put in a great deal of upfront design-for-manufacture work before these specialists design the moulds.

“Even as we’re creating the base models, we’re breaking down the geometry, we’ve always got a plan of how the parts are going to work together, so that as we build our surfaces, we can make sure that the curves represent the draft angles of the final parts,” he says.

“So all of the data that we send out to the toolmakers has always been through a check-in process to make sure that draft angles are suitable, there are no undercuts, there are no overly thin edges, consistent wall thickness, and areas to place ejector pins. All of that is up to us, so that we can control the output from third-party toolmakers and manufacturers.”

The design process for Scalextric is pretty similar, with the major difference that parts are designed for third-party manufacturers to build and assemble before they reach the customer, says Oscar Thornton, senior product designer on the Scalextric team. Data is brought into Creo from similar sources – from original manufacturers, and sometimes CAD files in the case of newer cars, along with scans. “We use this as a base, something to trace over, essentially, and then we develop our skeleton model and follow the same process from there,” he says.

“But in addition to the fact that our end product is built and assembled and painted by a manufacturer, it’s also different from the point of view that it gets handled by the customer a great deal, thrown around a track, so it has to be designed to be able to withstand some rough treatment, survive a few knocks and so on.”

That’s particularly true for the Micro Scalextric system, an introductory product for younger children that’s designed to be simple for them to put together and start using with a smaller handheld controller. The cars in this range are a bit more stylised, and share a standard chassis which is used as a reference point and skeleton for every vehicle in the range. But while Micro Scalextric cars are generally pretty simple, other Scalextric cars might have as many as 20 to 30 different components, and these also follow a top-down design from a skeleton, too.

Hornby Hobbies – Making the most of 3D data

Another thing that different brands under the Hornby Hobbies umbrella have in common is the mission to get the greatest possible use from the 3D data created in Creo by product design teams, says Jamie Buchanan.

The 3D printing of product design files as prototypes is one of the most important areas in which this happens, he says. In the case of Airfix, parts are 3D printed to doublecheck that these can be assembled by the end customer in the way the product designer intended. A conflict here could prompt a design change, perhaps by splitting the components in a different way. In the case of Scalextric, it’s more often about the performance of a car – for example, checking that extravagant tail fins don’t destabilise the car when it’s running round the track.

Says Whiting: “We tend to do all the STL conversion here, which means we can control how many vertices are in the STL. That’s something we like to do ourselves, in order to get the very best conversion, by finetuning all the settings in Creo. As a consequence, although most 3D printing is done for us by outside companies, we get very high-resolution parts and high-quality output.”

Data from Creo is also used in marketing, says Buchanan. “If you look on our website, many of the representations of products are directly derived from that data. The same applies to box-front imagery for Airfix. It’s basically our 3D data in the form of renders, produced by our render guys.”

A great deal of 3D data is also taken into 2D via Adobe Illustrator to create product artwork. “This artwork is issued for all brands except Airfix to our manufacturing partners. So along with the 3D CAD data that they use to make the tooling and the mouldings, we also give them some 2D files that contain a lot of reference data regarding how we would like the end model to look and how we want it decorated,” he says. For Airfix, meanwhile, 3D data is converted into rich, stage-by-stage, illustrated instructions using PTC Arbortext Isodraw.

“Alongside Root Solutions, we’re just starting to look at how we could use our CAD data on our websites, so that customers can get a really good feel for a product and be able to spin it around and so on, before they buy,” adds Buchanan.

“That’s particularly important for Airfix, because what you get as a customer is a bunch of sprues in a polythene bag. By using the CAD data that Matt and his team create, the purchasing experience could be so much richer.”

He has little doubt that new uses for 3D CAD data will emerge in future, as the company continues to expand its product line and broaden its appeal for younger generations of hobbyists. “This data is the result of a huge amount of skilled and painstaking work by our expert product designers. It has real value for us as a company and for generations of hobbyists. Why wouldn’t we want to make the most of it?”