Airpulse founder Phil Jones is looking to create audiophile sound quality without the audiophile price tag. He speaks to Stephen Holmes about the advances in simulation and testing that help to achieve this goal

When designing loudspeaker systems, Airpulse founder Phil Jones likes to work from the ground up, ensuring that all aspects of design and engineering fit the concept precisely.

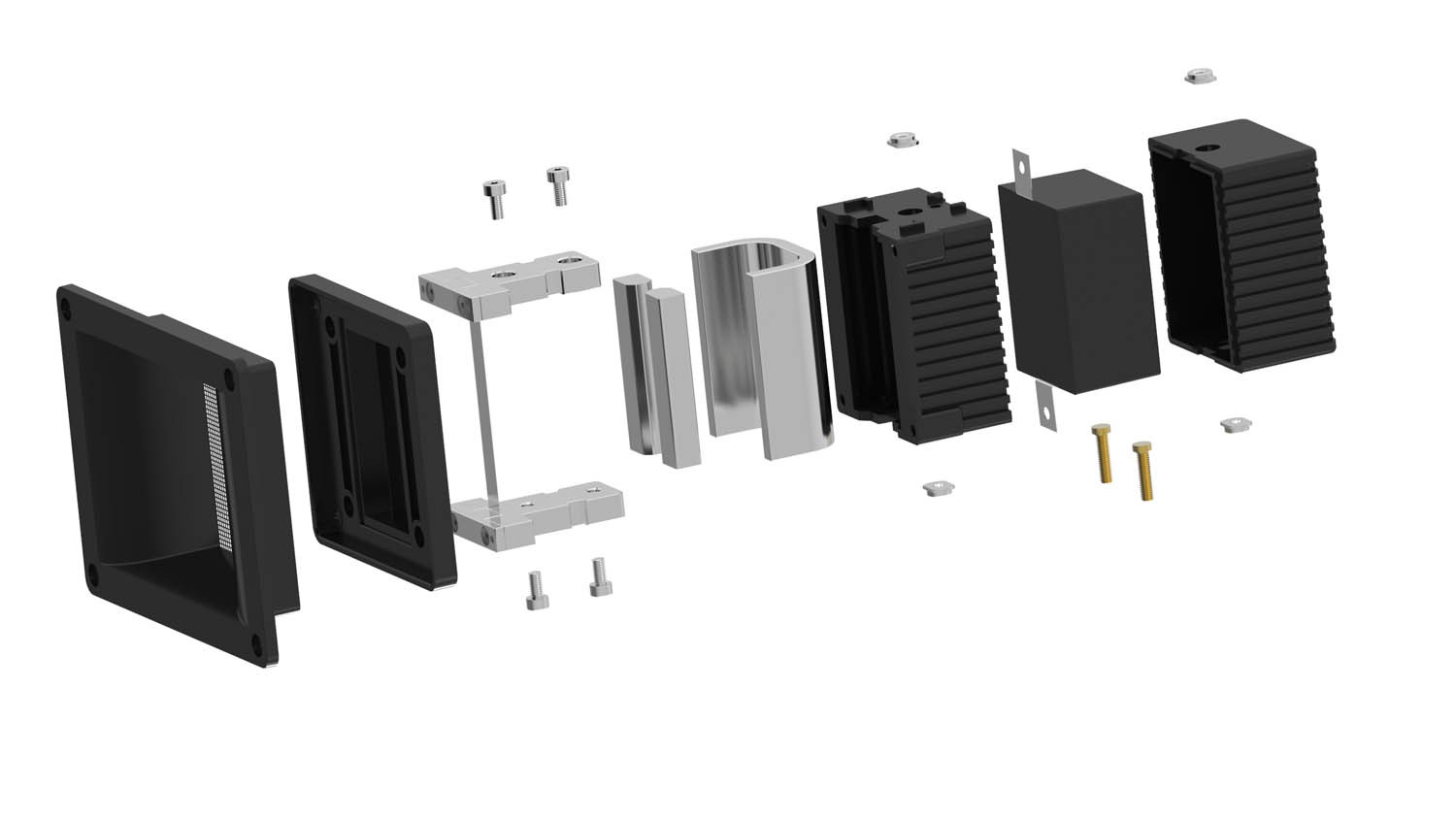

For example, with a home bookshelf speaker like the Airpulse A300, the experienced loudspeaker engineer works with his industrial design team to ensure the product looks just as good on that shelf as it sounds.

“Very often, industrial design does not follow the laws of acoustics, so it is very important that I lay down specifics for the ID team to work around,” Jones says from his US home. Typically, this involves using AutoCAD for mechanical drawings and Autodesk Inventor and Solidworks for 3D CAD work.

“From my 40 years of speaker design, it has become almost an instinct for me to create transducers. However, we also need to make many sophisticated electrical, mechanical and acoustic measurements, so I can see how good – or bad – my design actually is!”

Born and raised in London, UK, Jones initially aspired to become a famous bass player, yet discovered his real talent lay in designing loudspeakers. Having worked for numerous brands, he went on to found his own Airpulse label.

A partnership with Chinese audio manufacturer Edifier has meant more control over the end product for Jones, and all the benefits of access to the booming Chinese audio manufacturing industry.

Airpulse – New tech, old problems

Even with the latest technology, Jones explains, loudspeakers are far-from-perfect devices, since they are “not linear”. In theory, a cone speaker should move exactly with the motion of the voice-coil, like a piston. Yet due to the cone’s geometry, the elasticity of the material used and the suspension systems involved, it often reacts differently than expected.

“It can break up at fairly low frequencies, both concentrically and radially. This is stored-up energy, and it has nothing to do with the true electro-mechanical motion of the voice coil,” Jones explains.

A Doppler laser interferometer is used to scan the cone as it is subjected to an audio input, allowing engineers to look at it under any frequency in a 3D or 2D cross-section, helping to weed out imperfections.

The speaker requires extensive auditioning in a variety of rooms and playing different kinds of music. For this, Jones uses a free software, Room EQ Wizard from Room Acoustics Software. He describes this as an “awesome piece of kit”, which works well with a variety of hardware.

However, nobody has yet created software to test speaker vents for air turbulence, he adds. The air speed through the vent tube on a loudspeaker can reach up to 70 mph, and with air passing both in and out, the velocity can generate a lot of turbulence. This, says Jones, is heard as distortion, “kind of like a chuffing sound in the bass”.

To combat this in the Airpulse range, the vent tube design was 3D-printed for wind tunnel testing, allowing the designer to iterate on its initial oval design with a parabolic flare at both ends.

Physical testing to this day helps to hone the sound, and with 40 years of experience, Jones has an accurate ear for pleasing customers new and old.