This year marks the twentieth anniversary of the Nissan Design Europe studio, a facility hidden in plain sight in the heart of London. As the studio team celebrated the launch of the Nissan 20-23 concept car, Stephen Holmes paid a visit and discovered more going on at this location than passers-by would ever suspect

It is two decades now since Japanese automaker Nissan opened a dedicated London design studio, housed inside an old train shed that played an important role a century earlier in the modernisation of the city’s transport network.

The Nissan Design Europe (NDE) site is a short walk north of the London Paddington rail station and lies on the footpath of another Victorian London engineering marvel, the Grand Union Canal. Every day, joggers, office workers and tourists pass by, and most of them don’t have any idea of what goes on inside this Grade II-listed, low-rise concrete structure.

Once through its sliding glass doors and zen-like garden reception, the space opens up like something from a James Bond movie. Light, open areas occupy three levels, often overlooking one another and teeming with scale models, display walls and full-size clay prototypes.

With its better access to natural light, the top floor is occupied by the interiors team. The mid-level, meanwhile, is assigned to exterior designers. The lower floor – the former rail repair bay that runs in a loop through the building – is devoted to physical prototyping and clay modelling.

Today, huge graphics of a new concept car, the 20-23, are emblazoned on digital screens and wall art surrounding the design team’s desks. An all-new vision for urban electric transport, the 20-23 began life as a fun project intended to reinvigorate the design team, explains Nissan Design Europe vice president Matthew Weaver, fresh back from picking up the car’s first award in Paris the night before. “Nothing too serious, it’s just for fun – for us,” is how he characterises the initial thinking behind the project.

“This was definitely just our ‘therapy’ present to ourselves,” he continues. “But it’s interesting seeing the traction within the company. It’s funny: to make people enthusiastic, it’s a lot easier when you put something like that in front of them, and that was the purpose of it: to get people reacting. At the moment in the company, there’s quite a lot of noise around it. So most of the studying of this as a commercial viability still has to be done.”

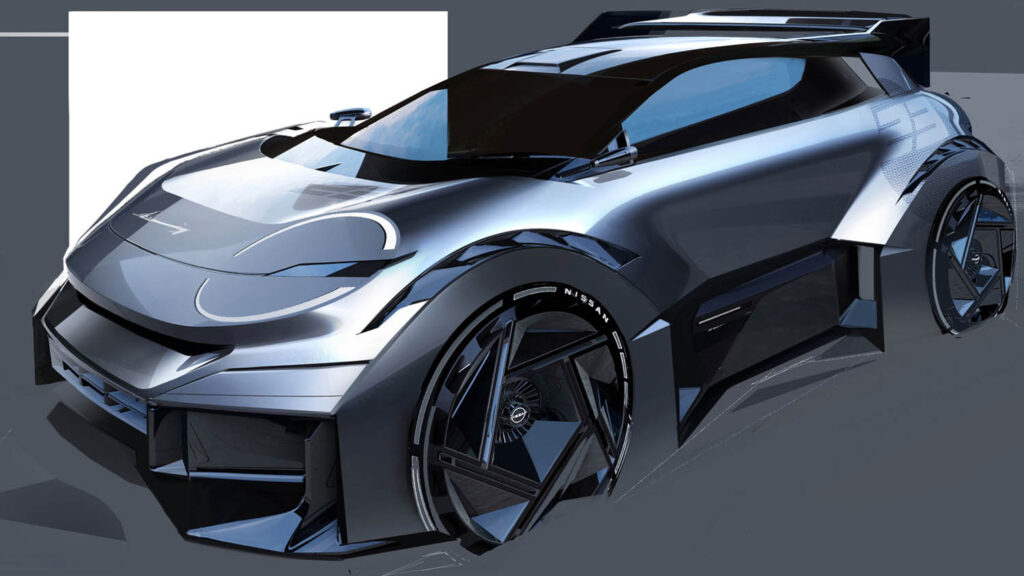

It’s easy to see why the Nissan 20-23 concept car has attracted so much interest. As a package, it appeals to multiple demographics. It’s squat, chunky, sporty, yet not overly aggressive, with softer lines and clever light placement that gives it a friendly face.

“What would you like to see driving around the city?” That was the brief presented to the team of designers, with the focus firmly on electrification and teasing out what the ‘new desirable’ might look like in an EV for urban driving.

“Ironically, the footprint didn’t start by growing. It started by reducing in size, because of nimbleness, even though it’s pretty wide,” says Weaver. That set the proportions, he says, and the games-mad team also took some inspiration from gaming. From there, the aesthetics started coming together. But as it was developing as a 1:1 clay model, older team members began congregating around it, he says, talking about World Rally Championship cars. It was a meeting of minds and ideas from different generations, it seems.

Says Weaver: “The car’s easygoing, with the priorities on different things rather than, you know, the ‘old formula’. But we wanted to appeal to and, if you like, convert the petrolhead.”

Swift development

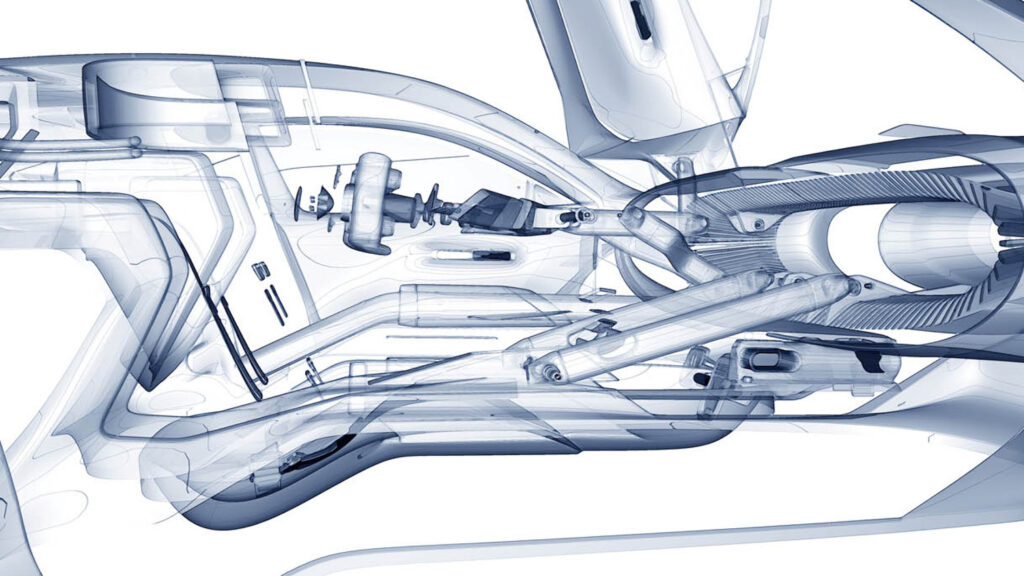

The process of developing the 20-23 was swift, with the whole team offering up ideas, and eschewing pen and paper sketching in order to jump straight into digital tools. The proposal was refined in Autodesk Alias, using the Wacom Cintiq Pro displays on every desk. Even the earliest 3D models benefited from swift connection to Autodesk VRED, giving enhanced render quality and direct integration for virtual reality.

“It’s got full collaboration built into it, so it’s like an allencompassing tool for visualisation and design review,” says Mike Jupp, manager for design realisation & technology at NDE. “So you can do the quick design, imaging for your high end marketing stuff, the VR and your collaboration.”

The team narrows down its ideas, with one key designer focusing on either interior or exterior, before Jupp’s realisation team approaches the design, working digitally and in clay.

Weaver suggests that the studio is unique in its balance and blend of both digital tools and clay modelling, circulating iterations through clay back into the digital realm via 3D scan data, and then adding any changes back to the clay.

“That’s the hybrid way. We do full digital or full clay sometimes, depending on form or who’s actually available, because we’ve got some great craftsmen down there [working on clay]. We’ve got some great minds up here as well [in digital surfacing]. And actually, the output is quite interesting – it’s quite different.”

Weaver says that an experienced eye can often spot a design that’s more influenced by digital versus a clay model. Both mediums offer benefits: shapes and surface treatments can work better in digital, while sculptural elements or tricky volumes can be better balanced in the physical realm.

There are strong points to both. VRED is invaluable when it comes to showing the car in different contexts: environment, lighting, colour. Clay provides a different means of fine-tuning highlights. The lower floor workspace, with its three plates for positioning claymodels and its open plan visibility to all design team members as they move through the building, acts as a constant reminder of where a project is in its development and how far is left to go.

Nissan models including the Qashqai and Juke – designs that spawned new market segments – were modelled here on the plates of the NDE, with the studio’s influence touching on global designs like the Patrol, GT-R and the electric Ariya.

In the early days of the NDE, a clay model would be wheeled onto an aeroplane and flown to Tokyo for review at head office. These days, in terms of sustainability, it’s a lot better for that process to take place as a virtual reality (VR) call, says Weaver. And it takes up a lot less time, too. Today, in the time it would previously have taken to accompany a clay model on a round trip to Tokyo, he points out, “we’ve already done three or four iterations digitally and shared it.”

The journey from sketch to production line is speeding up thanks to technology, but what has also improved is the ability to work closer with colleagues in engineering or marketing, wherever they are in the world. “

[In VR] they can see immediately what the car is. Whereas actually showing them an undressed clay model doesn’t serve the same purpose. So already it helps the minds further down the process understand what the product is, let alone speeding things up.”

Impact of new tools

“Any technology is still a tool to do the job, but things are definitely changing,” says Weaver, who has led NDE for three years as its vice president. Prior to that, he was design director, and before that, he spent ten years in Japan as a design project lead on the global design team.

“The thing we’re already noticing in particular is AI, for example. It’s easy for things to converge – iterations of iterations – but actually, when we look at how we design cars, we’re trying to diverge. So, it’s fine if AI gives you stuff that we don’t even know yet. That’s a great bonus,” he says.

Nissan is already making plans to run broader trials of AI software like Vizcom, which turns sketches into concept renderings in seconds and can be reiterated by the designer. #“We don’t mind how ideas come along. The way that they’re generated, it’s kind of strange, because the discipline of sketching is such a fine art, but sketching takes so long to master. Now it’s quicker.”

Weaver is intrigued by the idea of AI one day producing car surface language as a pure aerodynamic form, as opposed to CFD simulation analyses offering up results, helping designers to ‘look for the cracks’ and dig deeper into their design work.

“That’s where you get little breakthrough moments, as you know – form and function. Something that really works. A eureka moment.”

He explains an accidental example that was found on the C-pillar of the Nissan R35 GT-R, where a styling element generated a vortex that had an unexpectedly positive effect on the rear wing. “So, not only does the style feature, it became functionally aerodynamic. You kind of have lucky moments like that.”

With the 20-23 being an EV, the importance of aerodynamics can’t be overstated. When engine cooling is no longer a necessity, various scoops and vents look to make the form as invisible to air as possible. The three-door, hatchback body style features extreme aerodynamic addenda front and rear, with deep skirts to direct the airflow away from the front of the car, through apertures to cool the brakes and out through vents just behind the front wheels.

“We’re learning so much about aero,” says Weaver. “It was always a bit of a dark art. You’d think that as a car designer you’d know everything, but we’re actually still learning, and interestingly, the aero guys are learning about exterior design, because what they’re saying has a massive impact on the proportions.”

The evolution of car design has come a long way. In the past, stylists would ‘car dance’ around a model, pronouncing their inspirations. Today, the Nissan team works closely with colleagues in the company’s head office in Tokyo, Japan; its R&D engineering team in Bedford, UK; and with global production lines. In short, designers now take a keen interest in build, cost of part, cost of tools, production line quality assurance – all the things that help develop a better end product.

Good sense of direction

In the winding corridors of the NDE, it’s easy to lose your sense of direction. Small staircases at sharp angles lead to dimly lit design areas or down to the lower floor where the realisation team works on physical models. A sizable milling machine for rough passes sits idle, but recently used, while its plate has been wheeled over to a spot underneath strip lighting for the first stages of manual sculpting.

Around the bend stands a GOM ATOS 5 3D scanner, recently brought in as an update to the Triple Scan variant that NDE previously used. “The quality is better, it’s quicker” says Jupp, adding that speed is its purpose: to quickly get point cloud data from clay back into digital, so a surface model can be digitised, even if just for some quick visuals.

If that is taking physical into the digital, then the Nviz compact driving simulator set up next to it supports the process in reverse, putting the wearer of a Varjo XR-3 HMD into a physical seat to review interior designs. “We always found that doing it the old way, with a VR headset and trying to get somebody in the seat in the correct position every time, was hit and miss. This system takes all that out of the way because you punch in all of the package information for that interior,” says Jupp.

“Nviz put it together for us. They develop their own Python plug-in for VRED, so it talks to all of the actuators and the controllers on the back, and it’s all moved within VR to match VRED to what’s going on physically.”

While the team is not necessarily interested in precision when it comes to the ergonomics involved, the designer in the driving seat still assumes the proper driving position with all viewpoints, touchpoints and instruments in the right place. A colleague, meanwhile, can jump into the passenger seat, to get that particular perspective and to collaborate.

Moving further around the bend of the building is an Aladdin’s cave of prototyping and machining. A Stratasys Fortus, a Stratasys J750 and a Formlabs Form 3 are used for quickly 3D printing parts that are either added to 1:1 scale models or used as scaled-down versions for internal reviews. A display cabinet in the public-facing window at the main entrance is regularly updated with a perfect scale model, as a declaration of what actually happens in the building.

A woodshop with a 5-axis Belloti mill takes up a generous amount of floor space in what Weaver suggests must be one of the world’s most expensive workshops in real estate terms. “We’re quite unique, socially,” he says. Directly across the canal, on desirable Warwick Avenue, an apartment with a similar square footage would cost its buyer millions of pounds.

Most automotive design studios are located next to R&D centres, often on huge out-of-town complexes or campuses. The NDE building, by contrast, nestles among the new office towers of Paddington Basin and the leafy pathways, ducks and canal barges of Little Venice. It’s very much part of urban London.

Staff have the option to drive to work, but there’s also ample public transport and of course the chance to get out after work and socialise with colleagues.

“Influences are coming in, problems are solved around a table with a beer or something. It all goes into the melting pot,” says Weaver.

With the idea of what a car represents as a product, and opinions about the positive impact of cars being debated, these viewpoints and chance sparks of creativity among the design team can be hugely influential.

Weaver notes that Nissan, in common with almost all automakers, is doing a lot of work around sustainability and zero emissions, but the goal is to keep the positive connotations of cars – the freedom, the self-expression – and take away the negative ones.

“I think it’s just morphing,” he says of the public perception of cars, before referencing a perfect scale model of a Nissan Figaro sat in a glass case. The car only saw a single year of production in Japan, based on a Nissan Micra platform, but built a lasting cult following with several thousand imported into the UK.

“The Figaro was all about that: approachable, a car that is not threatening in any way. It’s like a pet, a friend, something like that. Almost for people who don’t like cars,” he says.

“So I’m really interested in that topic. Nissan, of all companies, plays with that quite well because of the Japanese image. So, the Kei cars that we’ve got, the Pike cars – the S-Cargo and Figaro were those. They kind of pushed the boundaries of moving cars towards that of a character or pet,” explains Weaver. “I think it’s a super cool kind of area for automotive.”

With its short wheel-base, smiling eyes and city smarts, the 20-23 is a vision of mass-appeal, modern-city driving and an exciting launchpad for the next two decades of creative work at Nissan Design Europe.