Rapid prototyping and 3D printing technology has had a huge impact on the manufacturing industry.

Manufacturers can build up end-use components and products layer-by-layer that rival those made with traditional mould and die manufacturing techniques.

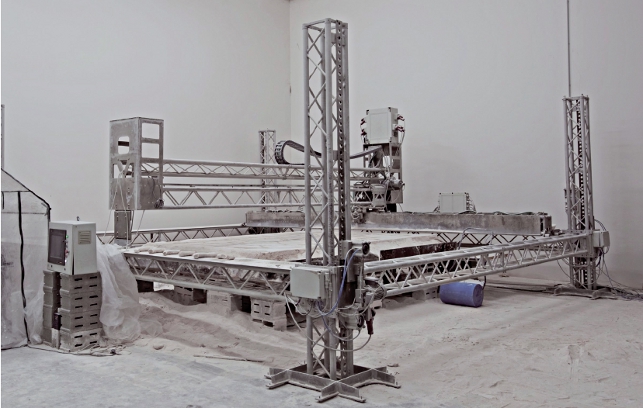

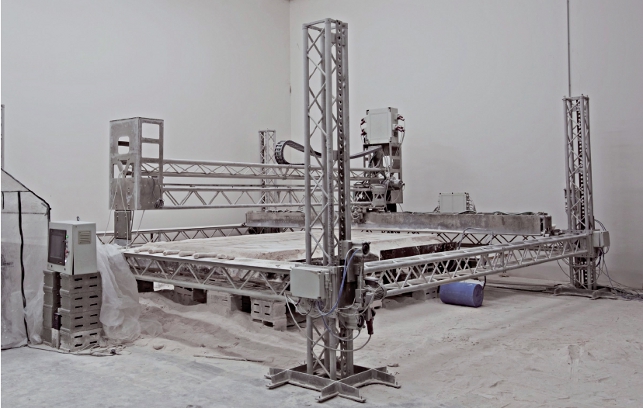

The D-Shape machine is a large aluminium gantry structure, which uses CAM software to drive a huge print head during the building process

Within the Architecture, Engineering and Construction (AEC) industry, however, such additive manufacturing processes are mostly limited to scale models of architectural designs, which are used to help visualise designs or to present 3D information in a form that everyone can understand.

One of the most popular technologies in this field is from Z Corp, a US company that uses technology borrowed from inkjet printers to literally ‘print’ a model in 3D. Using a combination of loose powder and binder, Z Corp’s machines can build a physical model, layer-by-layer, and in a matter of hours present a finished design in glorious 3D that architects and engineers can pick up, hold and interact with.

Dream ticket

But what if you could print an entire building this way? Put a machine on site and set it going to automatically construct an entire building? This is the dream of Italian born Enrico Dini of Monolite UK, who has already created D-Shape, the largest 3D printer in the world, capable of printing sandstone structures up to 6m x 6m in plan and with little to no human intervention.

The binder transforms any kind of sand into a marble-like material with a resistance and tranction much superior to Portland cement

His largest structure to date, the Radiolaria, is a 2m tall sculpture inspired by the architect Andrea Morgante, but Mr Dini has already started work on a full scale, 8.5m high version, and that is only just the beginning.

Without the need for formwork and traditional labour, Mr Dini believes the impact on the construction industry could be huge, in terms of reducing both time and cost. With the technology able to build complex architectural forms, just as easy as it can produce rectilinear structures, it could also have a major impact on the face of architecture.

Mr Dini’s dream began in 2004 and he immediately acknowledged that in order to ‘print’ 3D buildings he would need to design a brand new technology rather than adapting current 3D printing technologies, which are designed to print minute amounts of material.

The primary challenge was to find a binder that would be able to fuse a granular material, and would have sufficient structural strength for a ‘printed’ building. His first attempts focused on epoxy resins, but he came to the conclusion that they not only suffered from technical challenges, such as flammability and toxicity, but they were far too expensive.

Instead he started researching and developing a new binder, made from environmentally friendly materials, which would be combined with a sand/stone powder-based granular material to make an ‘artificial stone’, with similar physical properties to sedimentary limestone. From here he refined the material to reduce lithifaction over time and improve waterproofing.

Proving the strength of such a material is essential to its success and the artificial stone has been subjected to a range of traction, compression and bending tests. According to Mr Dini, the results have been extraordinary.

“The binder transforms any kind of sand into a marble-like material (i.e. a mineral with microcrystalline characteristics) with a resistance and traction much superior to Portland cement, so much so that there is no need to use iron to reinforce the structure,” he says. “This artificial marble is indistinguishable from real marble and chemically it is 100% environmentally friendly.”

Enrico Dini has also worked with Belgian rapid manufacture specialist, Materialise, to produce bespoke limited edition furniture such as this chaise longue

The printer

The D-Shape machine is a large aluminium gantry structure, which uses CAM software to drive a huge print head during the building process. Like traditional rapid prototyping machines, the powder (in this case sand) is laid down and then cured with a binder. Excess material acts as a support to the binded structure and at the end of the process this is removed and can be reused.

With a current build area measuring 6m x 6m, accuracy is very important and in order to raise the printer head precisely it requires an extremely rigid frame. Despite these structural requirements, the machine is light and according to Mr Dini can be easily transported, assembled and dismantled in a few hours by two workmen.

In order to achieve the kind of speed required to construct a building, the machine features 300 nozzles on a 6m print head. Moving across the print area it is capable of producing one 5mm layer every four to six minutes.

Of course, the volumes of material involved in the process are not trivial. On a 30m sq building it needs 150 litres of ‘sand’ for each layer, which, with a print rate of 30cm-40cm per day, is the equivalent of 15 tonnes of sand per day. Given additional funding Mr Dini believes he could build a machine to operate at 1m per day, which would mean building a two storey house in 15 days.

Scaling the technology so it can build even larger structures is not a technological barrier. Additional funding would make this possible and plans are also underway to increase the resolution and reduce layer thickness to add detail to the structure and reduce the need for hand finishing.

Cost is a major driving force behind the D-Shape technology. Structures currently come in at €1,000 per cubic metre, but the goal is to bring this down to €250 per cubic metre or less. According to Mr Dini, despite the higher cost of the binder compared to Portland cement, the realisation costs of D-Shape structures are 30%-50% lower than manual methods, which involve the production of formwork and labour.

The future

Mr Dini is continually looking to improve the printing process, not only enhancing the resolution of the system, but developing walls or shells with integrated building services and improved thermal properties and acoustic absorbance. For more organic structures, additional research is also being carried out into forming joints in a single process and the use of post tensioning reinforcement.

A major attraction of the technology is its ability to work with local materials. While in more traditional terms this means any type of sand, dust or gravel, the D-Shape technology is also being lined up to print a building out of Moon dust. Mr Dini has been appointed by the European Space Agency to undertake this research project and the D-Shape will initially print a concept based on a simulant of lunar soil with a view to building a structure on the Moon’s surface in 2020.

Back on Earth Mr Dini is a huge fan of Antoni Gaudi and many of his dreams centre on the Catalan architect’s work.

The organic forms prevalent in his designs are perfectly suited to the D-Shape technology. Within five years Mr Dini is confident that he will be able to build a portion of Gaudi’s Casa Batlo, with a structure ensuring strength, thermal, and mechanical properties.

His dream, however, would be to complete one of Gaudi’s unfinished buildings, the Church of Colònia Güell in Barcelona. For a man who has put his heart and soul into printing 3D buildings this would be the pinnacle of what looks certain to be a fascinating career.

www.d-shape.com

The Personality behind D-Shape

Like his father before him, Enrico Dini (pictured above) trained as civil engineer, but he chose to work with his brother in automation and robotics in the footwear, automotive and marble industries.

This offered him more of a challenge to solve problems as the majority of civil engineering projects in Pisa, Tuscany, his home region, involved fairly repetitive work. Here, he gained experience in offline programming CNC machines, which he has since applied to the idea of construction-scale rapid manufacturing.

The Radiolaria

Enrico Dini’s largest structure to date is the Radiolaria, a 2m tall structure inspired by the architect Andrea Morgante.

The structure was modelled in CAD, then stress analysis software was used to validate its integrity without having to add additional reinforcement. The next stage was to export to STL, the industry standard for rapid prototyping, and then import the file into D-Shape’s dedicated software ready for ‘printing’.

It took ten days to print the structure, which included a containing shell comprising the binded model and loose sand, which was carefully removed by hammer. Mr Dini admitted that he was afraid that the structure would collapse during this process, but to his relief it remained intact. It was then hand finished to add to its aesthetic appeal.

A full scale, 8.5m high version of the Radiolaria has been commissioned for installation in Pontedera Italy later this year.

This will be located on a roundabout and due to the scale Mr Dini admits that it will be impossible to print on site, so he is currently working out how to assemble piece by piece and at the same time maximise the number of components that can be printed in a single build.

Due to scale of this structure it will also require reinforcement as he cannot be confident that the strength of the stone material alone will be enough to support the structure.

Tech Specs

Build area

Current – 6m x 6m

Output printing resolution

Current – 2dpi-4dpi (target 12dpi-25dpi)

Layer Thickness

Current – 5mm-10mm (target 3mm)

Tensile strength

Current 35-55 kg/cmq (target 80-100 kg/cmq)

Printer process cost

Current €1,000 / cubic metre (target €250 / cubic metre)

The D-Shape advantages

• Automated construction

• No formwork

• Freedom of geometry

• Materials used are abundant

• Similar fire resistance to concrete and stone

• Material strength higher than concrete

• Low waste

• Environmentally benign and recyclable

Squeezing the tube

Enrico Dini is not the only one investigating the potential of large-scale additive manufacturing for producing full-scale building components. The Freeform Construction project (www.buildfreeform.com) at Loughborough University, led by Richard Buswell, has its own take on the technology.

Freeform Construction has investigated a number of additive processes, but the project has focused on using traditional construction materials such as gypsums and cement-based mortars. The technique is called concrete printing, but unlike traditional powder-based 3D printing processes it deposits a ‘liquid’ concrete – think squeezing a very big tube of grey toothpaste. The machine uses a gantry and can produce components in a build volume of up to 2m x 2.5m x 5m. The project has already delivered a one tonne reinforced concrete architectural piece.

Dr Buswell explains that the challenge has been to develop components that are not only aesthetically pleasing but can be tangibly used as part of the construction process. This not only means understanding the strengths, weaknesses and physical properties of each process, verified through compression and flexural testing, but the importance of precision in relation to fabrication.

“If we are going to produce real components in buildings that are likely to be components that will fit together, things like tolerance are very important,” he says.

This focus on precision has also resulted in research into manufacturing walls with voids that can accommodate building service requirements such as pipes and cables.

Sand and deliver – a new dimension in prototyping