As summer sees travellers return to the skies, aircraft makers are finding innovative ways to control in-cabin airflow. Stephen Holmes speaks to Pexco about how the company has engineered a creative solution to keep passengers breathing easy in their seats

Controlling airflow on passenger aircraft has never been more important. Yet long before Covid reared its head, designers and engineers were already working on improving the onboard experience for passengers.

Pexco Aerospace was one such company looking to improve air circulation in plane interiors — keeping air moving not just along walkways and around passengers’ heads, but right down to the HEPA filter collection points by their feet. However, as the company’s engineers researched this idea, they quickly discovered they were not alone. At product design consultancy Teague, others had already developed a concept that could be retrofitted to ‘gaspers’, the ceiling vents above passengers.

A partnership between Pexco and Teague soon followed, in which Pexco acquired the rights to Teague’s design. “We felt like [Teague] was trying to accomplish the same thing we were: we had patented the sidewall technologies and they had started the patent process of this AirShield technology. So we really felt like we had it pretty well covered,” says Pexco president of aerospace, Jon Page.

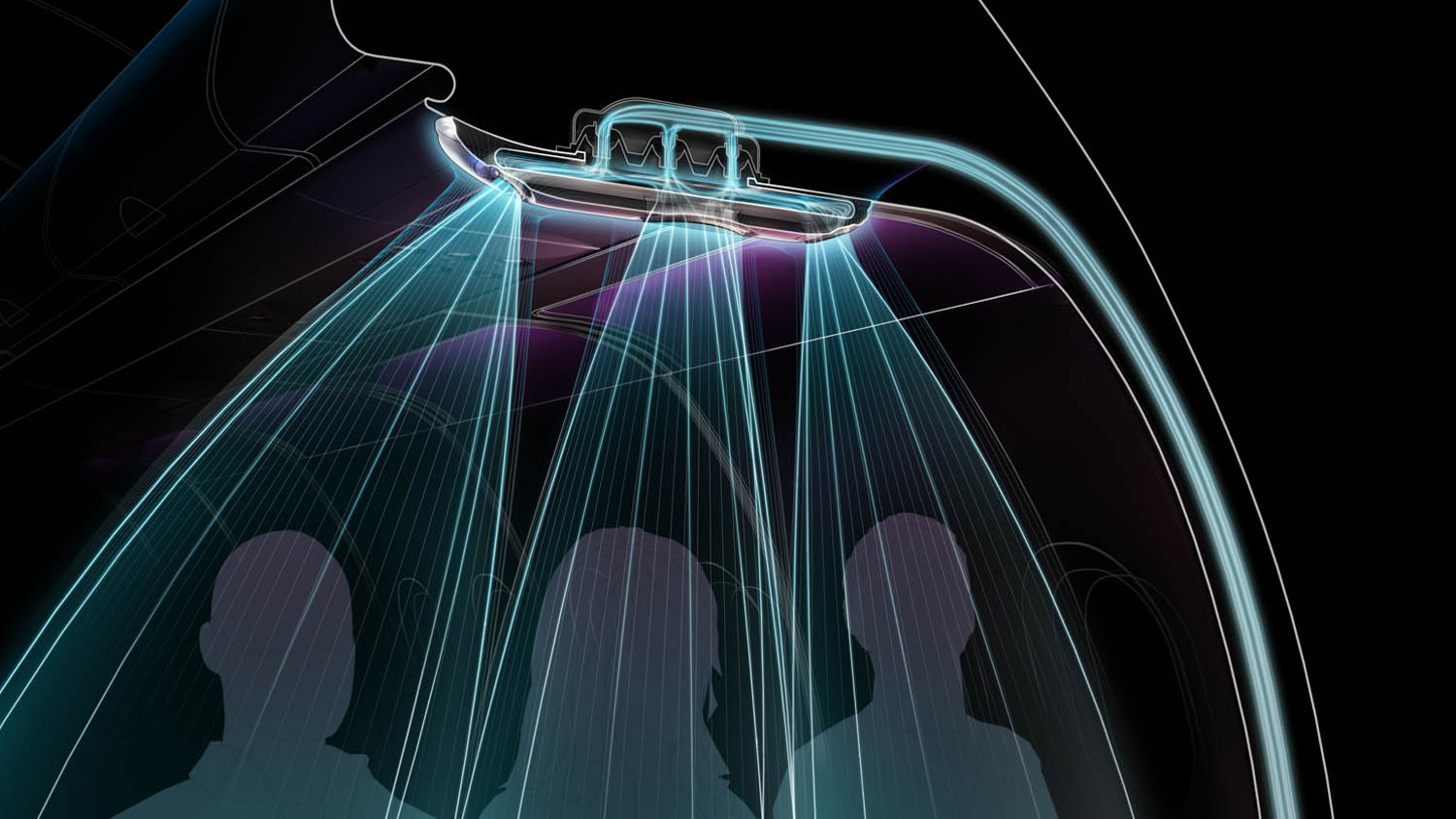

The AirShield design, installed over the top of existing air vents, repurposes purified air from the HEPA filtration systems, in order to create protective air barriers around and in between each passenger. Nozzle tips harness the Bernoulli principle, drawing in surrounding cabin air and doubling resulting airflow, while also reducing shared air particles between neighbouring passengers in an economy cabin by 76%.

The focus for the initial design was narrow body passenger aircraft, specifically the Boeing 737 and Airbus A320, says Page. There’s more of them around and more people flying on them, he reasons, especially as the industry bounces back from Covid.

Free flow of ideas

Initially, the team started by assessing CFD performance, building on what Teague had done using Ansys Fluent, adjusting the CAD designs in Solidworks, and then creating over 20 different versions that were then 3D printed for physical testing.

The ability to prototype so many iterations was a key factor in perfecting the design, especially given the size of part and the cost of its tooling, which would run to around $600,000 to cut.

Using its in-house 3DXTech Gearbox HT2 3D printer to produce single-piece FDM prototypes, the final design was then reengineered to make it easier to manufacture using injection moulding.

“We went through that whole process so that, when we engage with our toolmakers, we understand, ‘Can we get this undercut?’, and ‘Can we do all these things?’” explains Page. “When you get into mass production, we have to go to injection moulding.”

The innovation doesn’t end with the tooling. Pexco has a long history of polymers development, creating unique formulas to match every part’s niche requirements and enabling them to fully pass strenuous FAA testing.

“The requirements are a lot higher for fire protection, and it has to be lightweight, but also incredibly durable. So, it’s not like a standard type of plastic. It’s very specialised,” says Page. That’s why Pexco invests in technology and personnel to be able to produce its own highly customisable substrates for plastics, giving it market agility.

For AirShield, this means Pexco was able to add an anti-bacterial additive to the polymer — important, given its function and position in the cabin. “Because if [passengers] see it, they’re going to touch it!” laughs Page. “Even though they can’t really adjust it, they’re gonna see something new!”

Fantastic plastic

The supply chain challenges of recent years have seen Pexco move further into specialty polymer production, says Page.

“We’re seeing air people calling us daily asking us if we’ve got 200lb of this, or 800lb of this, or 1,000lb of this. And it’s been very interesting; we’ve ended up becoming like a distributor of plastics by accident because of supply chain challenges.”

This knowledge has stood Pexco in good light, both with customers who want the lightest possible product, and with testing authorities that need it to meet key safety standards.

“We know what makes it lightweight, but it also has to perform in the burn and the durability tests. We can make this AirShield bulletproof, but it would weigh six pounds and fall off the ceiling,” states Page.

The production AirShield will weigh under a pound, but is remarkably durable. “We’ve looked at a lot of different technologies for this in the future, to where maybe we can make it lighter by putting some recycled carbon fibre in and some other things, but right now, it’s about getting it certified and getting it on aeroplanes.”

Page remarks that aerospace is an extremely conservative industry – nobody wants to be the first until it has full FAA approval – but once AirShield achieves this (and at the time of writing, it was at the penultimate stage), then it is expected that take-up will be swift as carriers look to enhance the onboard experience and give improved air-quality assurances to passengers.

The use of AirShield, after all, is a powerful indicator that a carrier is doing everything it can to make journeys as safe as possible — a bit like the plastic barriers that separate staff and customers in a bank or supermarket.

“There’s a visual cue that this company is concerned with what’s going on,” says Page. And that will be a valuable reassurance for passengers, many of whom may be embarking on their first trip for some years.