A myriad of factors are considered at the start of a design process. Tanya Weaver grapples with just how big a consideration sustainability is and whether that encompasses designing products built to last

I’ve always been slightly in awe of product designers and how they are able to ‘magic’ a product into life. I think it’s pretty amazing that they can create something out of quite literally nothing – just an idea that becomes a sketch, then a model in CAD, a prototype to finally a finished product.

It must give such a sense of satisfaction to see one of your products on a shelf or in use and think to yourself ‘I did that’.

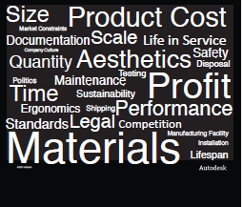

But, of course, bringing a product to life is no mean feat. Before pen is even put to sketchpad there are myriads of issues that have to be considered. This was really driven home to me by a slide that was shown during a recent Autodesk media briefing, which dealt with the new partnership between Autodesk and Granta Design.

As I’m sure you’re aware from reading last issue’s Sustainability Supplement, Autodesk Inventor 2012 users will now be able to access Granta’s extensive materials database through the Eco Materials Adviser.

At the briefing Sarah Krasley, product manager for sustainability in Autodesk’s Manufacturing Division, and representatives from Granta explained how this new tool will enable designers and engineers to make more sustainable design decisions at the earliest stages of the product development process.

During Krasley’s presentation she showed an interesting slide (right) from a 2006 Autodesk study that looked at the various issues that a product designer has to consider at the start of the design process.

“It is just amazing the amount of information that designers are weighing up and pitting against each other when designing a new product,” said Krasley.

With the word ‘material’ being one of the biggest in the slide, it clearly demonstrated to Krasley that a tool to help designers choose the best and most sustainable material at the front end of the process would be of great benefit.

However, although the word ‘sustainability’ is quite small, I’m sure that over the five years since the study was done it has become a bigger consideration.

This got me thinking that although tools like the Eco Materials Adviser and others geared towards sustainable design, like Lifecycle Assessment and light-weighting, are all well and good, surely another take on sustainability is actually designing products that are built to last. Rather than just designing a product that can be easily disassembled at end of life, design it so that its lifespan is longer to prevent its disassembled parts landing in the tip just two years down the road.

This is easier said than done of course especially when you consider the practice of Planned Obsolescence. Essentially this means purposely designing a product that will break down after a period of time.

The fountain of all knowledge, Wikipedia, states that ‘planned obsolescence or built-in obsolescence in industrial design is a policy of deliberately planning or designing a product with a limited useful life, so it will become obsolete or non-functional after a certain period.’ How unsustainable is that?

Of course, this also occurs in the software world. How often do software companies drop support for older versions of their software in order to pressurise users into purchasing new products or upgrading to the latest version?

In my opinion, if manufacturers are outwardly claiming on their Corporate Social Responsibility reports that they are committed to being more sustainable, then maybe they should stop producing products

with built-in obsolescence in the first place.

In Krasley’s presentation she also showed a great photo of 600,000 clam shell mobile phones that had reached their end of life. That is the amount retired in the US on a daily basis. More shocking is that this figure is from 2008. With the onslaught of new smart phones in the last couple of years, I dread to think what that figure would be now.

Vitsoe claims to design and manufacture against obsolence. Its motto is ‘living better, with less, that lasts longer’. Image if more complaints adopted that motto!

I’m not claiming innocence in all this. I too want a new mobile phone when my contract runs out after 18 months and I’ve also been known to frequent IKEA, a massive culprit in my opinion of built-in obsolescence. Its furniture is cheap and functional – the interior of my first house was like stepping into an IKEA catalogue. But I don’t particularly care for the products as I don’t attach any real value to them.

If they fall apart after a few years, I’m not too bothered. On the other side of the scale is furniture manufacturer Vitsoe, which claims to design and manufacture against obsolescence. Its motto is ‘living better, with less, that lasts longer’. Imagine if more companies adopted that motto!

But at the end of the day, if manufacturers sell more products more often they make a bigger profit. But in our more eco aware world, perhaps the word ‘longevity’ or ‘durability’ should make an appearance on this slide and be one of the considerations in the concept phase too.

Can a company design a product that endures, using less?