In the world of motorsport, it’s not only the cars that have to be fast but the speed at which they are designed and developed too.

Nissan DeltaWing

High performance automotive engineering company RML Group, which regularly has four to five programmes on the go at any one time, knows exactly what it’s like to work under pressure.

Founded in 1984 in Wellingborough, Northamptonshire, RML specialises in delivering touring car, GT, sports prototype and rallying programmes in major motorsport series and championships for a number of partners including Nissan, Vauxhall and Chevrolet.

Each project has a different scope and longevity with some just being months and others, such as the multiple championship winning World Touring Car Championship (WTCC) programme, many years.

The company consists of around 120 people, which includes a small design and engineering team. “When you tell people what you do for a living, they naturally jump to the glamour of the racetrack, but for me that is near the end of the process.

The journey starts sometime before (although never long enough for designers!) with the layout of the car in CAD,” explains Daniel Mense, RML design engineer, who has been with the company for nine years.

“People are often surprised to hear the detail that we go into for touring cars, such as developing our own damper design to improve suspension geometry or that we design our own engines, like the WTCC world championship winning engine in the Chevrolet Cruze,” he adds.

Best of both

One of RML’s long term partners is Nissan.

Since 1990 they have worked together on various touring and automotive projects, with one of the most recent being the Nissan Juke-R ‘super crossover’ in 2011. “Nissan asked us to come up with a concept to show the sports side of the Juke.

We came up with the idea of mating a Juke crossover road car with a high performance GT-R sportscar, which on a base level share a lot of the same technology such as torque vectoring,” comments Michael Mallock, RML business development manager who is also an ex-race car driver and RML’s chief test driver.

Although the exterior and interior may look like a Juke, under the bonnet is a 3.8-litre twin-turbo V6 engine that allows the car to reach 60mph in 3.7 seconds and a top speed of 160 mph. “We started the project in about June 2011 and the first finished test vehicle was shown 22 weeks later. So, it was a very short time period,” says Mallock.

Following the concept’s success, a small production run followed with the first customer cars delivered in mid-2012.

It wasn’t long after this project that RML was again approached by Nissan for another motorsport project – the DeltaWing, a radical race car that was due to race at 2012 Le Mans 24 hours, an endurance race held every summer since 1923 near the town of Le Mans, France.

The brainchild of Ben Bowlby, a Briton living in California, the DeltaWing prototype was initially designed to be the new 2012 race car for IndyCar, an American-based auto racing sanctioning body that organises the IndyCar open wheel racing series, including the Indy 500.

The aim was to create a highly efficient car that would use half the fuel, half the engine power and half the tyre requirement than any current IndyCar.

Weighing half as much also meant it would have less drag enabling it to go as fast or faster on the course. As the name suggests, it has a delta wing shape, with a narrow 0.6 metres front track and 1.7 metres rear track. With no front or rear wings, downforce comes from the underbody.

It wasn’t selected by IndyCar, who opted for a conventional Dallara design instead, however, Bowlby then presented his concept to the Le Mans sanctioning body – Automobile Club de l’Quest (ACO).

In June 2011, approval was given for the DeltaWing to run from ‘Garage 56’ in the 2012 race, the spot in the pit lane reserved for technically exciting vehicles.

Although many partners contributed to its creation, including Michelin who produced the bespoke tyres, the DeltaWing still lacked manufacturer commitment for an engine.

In the eleventh hour Nissan stepped up to the plate, which together with RML developed an ultra efficient and extremely lightweight 300bhp 1.6-litre four-cylinder turbocharged engine.

Although the brief to RML was initially just for the creation of the engine, as the project progressed it ended up running the whole project on behalf of Nissan working alongside Bowlby and his team, who were embedded within RML.

“It was the third quarter of 2011 that we kicked off the project for the engine design and by end of February 2012 the first engine was in the car. It was an extremely tight time period,” comments Mallock.

Challenges ahead

The testing period itself was also very tight as traditionally an experimental car such as this would be tested for at least 12 months, not just three. “From when the DeltaWing first hit the track on its very first test day, it was less than 100 days until the start of Le Mans,” adds Mallock.

This challenge was further compounded by the aim of making all the parts and components as lightweight as possible. Whereas the normal weight for an Le Mans Prototype (LMP) car is nearly 900kg, the DeltaWing had to weigh in at under 500kg in order to keep it within the limits that had been set for the performance parameters.

As with all RML’s projects, the design team jumped straight into CAD. For the past five years it has been using NX from Siemens PLM for CAD/CAE/CAM and product lifecycle management with support from Team Engineering, a Siemens reseller in the UK.

“Everything is done in CAD these days. With the increase in the reliability of the technology over the past few years, it has just sped up the process on these sorts of projects especially where weight is the key point.

With CAD you can get very accurate estimates of the mass of individual components, which helps when you are designing racing cars to be as lightweight as possible.”

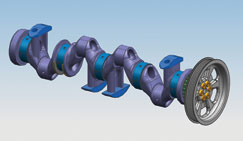

“One key area we focussed on in the design of the DeltaWing was the crankshaft, which is traditionally a heavy, solid lump. We put a significant amount of time and effort into making that as light as possible. We drilled a lot of holes through it and had counterweights in odd places – not the sort of thing you would traditionally see on a crankshaft but it looks pretty cool,” says Mallock.

The DeltaWing was also tested in the virtual world using FEA and other analysis tools to make sure that the stresses and vibrations all worked despite the extremely lightweight nature of the design.

Although RML’s design engineers relied heavily on virtual testing, further into the development process some of the smaller components were rapid prototyped such as the brake cooling ducts.

Evolving design

The design didn’t stop once the car hit the test track as there were minor tweaks to individual components right up until the start of Le Mans.

“The gearbox was the component that caused us the most issue and that was purely a factor of trying to hit the weight targets. But we got there in the end just before the race. It was all very tight,” says Mallock.

It was no doubt a stressful project to be involved in, but as Mallock says, being so exciting they could put up with the stress. “It was a fantastic project to be involved in and to be a part of something that was so pioneering and innovative.”

This view was not shared by everyone. Before this striking, black Batmobile-esque vehicle rolled onto the Le Mans starting grid, it was greeted with controversy with critics questioning how well it would steer and whether it would even turn corners. But this design was sending ripples out far wider than just the motorsport world.

“When we did the launch event in London, that night the DeltaWing was on BBC News Round. That’s the only time I’ve seen a race car on News Round,” says Mallock.

“Then the next day when we were out in the US and the DeltaWing was turning its first laps in public, we arrived at the hotel and saw the previous day’s London launch on Network News. That was when I knew it was really going to gather momentum outside of traditional motorsport press.”

Arrival at Le Mans

As a marketing tool for Nissan, the DeltaWing was a huge success when it reached Le Mans especially combined with the Nissan Juke with Ministry of Sound (see below), which also toured around the Le Mans race circuit.

In fact, Mallock reckons the DeltaWing probably received three times the amount of press coverage during the competition than the winning Audi did.

So, it was unfortunate that after all that hard work the DeltaWing didn’t actually finish Le Mans. It retired in the sixth hour after 75 laps after it was hit by one of the Toyota LMP1 cars.

Le Mans marked the end of Nissan and RML’s involvement with the DeltaWing but it has since gone on to race in Petit Le Mans, the American Le Mans Series, where it came fifth overall.

Back at RML as one automotive programme finishes, another begins and there are more than enough projects on the go to keep the design team busy especially with the company defending its world championship title in the 2013 WTCC with the ultra successful RML designed and built Chevrolet Cruzes.

“People outside the industry are often surprised to hear that working in Formula 1 is not the end goal for every design engineer,” says Mense. “The pinnacle of motorsport is certainly of interest technically, but it simply cannot compete with the variety and level of involvement that I get from working at RML. When that car wins a race I really feel justified in calling it ‘my car’.”

Music to your ears

As well as the Nissan DeltaWing, the limited Nissan Juke with Ministry of Sound also debuted at Le Mans 24 Hours in 2012.

Nissan’s brief to RML was to incorporate a fully self contained sound system, similar to what you’d find at an outdoor Ministry of Sound event, within a standard Juke.

“When the driver stops the car and presses the button, the boot opens and a huge speaker comes out the back. It is all completely automated, the mechanisms of which we designed in CAD,” says Michael Mallock, RML’s business development manager.

During the race weekend, these Jukes would tour around the race circuit, passing many of the 250,000 spectators, and would often lead to impromptu parties. “The Jukes would pull into one of the camp-sites looking just like a normal car and the boot would open, the sound system would come out and we’d have parties on the campsite. It was brilliant,” smiles Mallock.

“What we do with Nissan is very different to what other OEMs do on the motorsport side — they are all very secretive and focussed on winning and have lots of security guards outside their hospitality. Whereas Nissan is a very accessible brand and tries to involve everyone, which it certainly did at Le Mans last year.”

Radical racing from design room to Le Mans starting grid in record time

Default