Simulation technology is more accessible than ever before, writes Laurence Marks, so it’s a shame that we humans continue applying it to use cases that focus so much on the pointless and the trivial

What’s happening in the world of simulation? In short: nothing much, but it’s been a long time coming.

I’ve been in the simulation business for a while, since the 1980s in fact. That’s the best part of 40 years, during which I’ve generally worked in the mid-market sector. There isn’t really a low end for simulation, and I’ve never been a part of the big industrial aero and auto worlds.

From this, you can neatly divide my career into two halves. During the first half, I spent all my time having to explain to people that they couldn’t have what they wanted, and certainly not at a price point that made any sense to them.

And what did they want? They wanted CFD of rotating components, integrated vibration and durability workflows, fluid structural interaction, rapid analysis of bolted connections, achievable optimisation technologies, models which considered the structure of the material in the overall representation of the part — I could go on.

But these things just weren’t possible, not unless people were tackling truly high-end problems and were equipped with high-end budgets to match.

Yet oddly, the second half of my career has been spent trying to get these same people to invest in these same simulation technologies — only now, those technologies are far more usable and affordable. They’re within reach.

You might imagine that, as a result, there should have been some golden era of simulation technology adoption, when people could suddenly have what they wanted and were prepared to pay for it. If there was, I don’t remember it.

There’s no better demonstration of where we are today than the abundance of pointless simulations that are regularly shown off across the internet. These, and the promotion of ‘new’ workflows that would actually seem to hail from the 1990s.

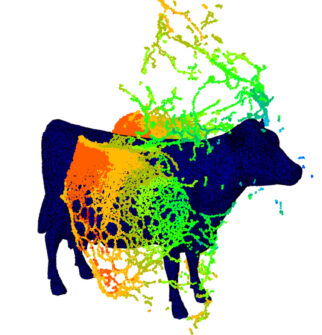

They are the equivalent of people who’ve just discovered ‘exciting new bands’ like Oasis and Blur. The world needs a lot of things, but fluid–structure interaction (FSI) simulations of cows falling over simply aren’t on the list.

Real work, valid use cases

What all this shows is that we’ve now got technology in abundance. It’s usable and it’s available at a price point where it is prone to waste (in other words, it doesn’t take a lot of costly compute power in relative terms).

But at the same time, it isn’t being used much for real work, because if it was, people would be busy actually selling, supporting and using it in proper, real-life industrial cases.

There would be no time for worthless bovine digital twins and nor should there be, in my opinion. Today, it’s arguable that for a lot of simulation work, cost isn’t a factor at all. I’ve got perfectly usable FEA and CFD systems that I downloaded cheaply from the internet. I’ve even got a pretty serious smoothedparticle hydrodynamics code that was a free download.

There are also systems out there like Altair OpenRadioss, a publicly available, open-source code base for non-linear problems, which is being worked on by a global community of researchers and developers. While I can say that I’m pleased I have this, I still can’t work out quite why they built it.

Twelve-core workstations and a decent GPU are achievable for many, allowing most tasks to be tackled in-house, and doing a respectable job of crunching the numbers without much of this having to head off into the cloud.

With Python now around, capable of stringing everything together into usable workflows, you’d expect every technical operation worth its name to be running extensive simulations wall-to-wall, night and day, chasing an ever-deeper understanding of the fundamental processes of their product’s make-up and function.

However, all the available evidence tells me that this isn’t happening.

Lack of vision?

I wish I knew why. For a long time, I ran a fantastic team of simulation engineers with extensive skills in composites, fracture and damage, FSI, biomechanics, CFD, production processes and much more. And what did they spend most of their time modelling? Machined, bolted and welded structures, mainly made of steel.

What we are up against here is not a failure of simulation itself, but more a lack of vision when it comes to applying it to engineering challenges

It strikes me that what we are up against here is not a failure of simulation itself, but more a lack of vision across the board when it comes to applying simulation to engineering challenges.

So now it must be, as it possibly always was, about the people. As I’ve made clear, the technology is out there, literally for the taking.

We need to lose the trivial stuff, to focus on real engineering simulations that will improve products, our understanding of how they work and of how they might be made better. Because if we don’t, nobody will – and that’s a scenario almost as depressing as those FSI cows.

This article first appeared in DEVELOP3D Magazine

DEVELOP3D is a publication dedicated to product design + development, from concept to manufacture and the technologies behind it all.

To receive the physical publication or digital issue free, as well as exclusive news and offers, subscribe to DEVELOP3D Magazine here