When you consider the development cycle that Autodesk’s Fusion 360 offering has been through, it’s quite remarkable.

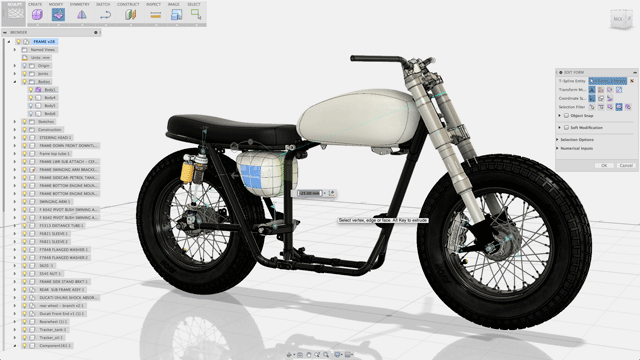

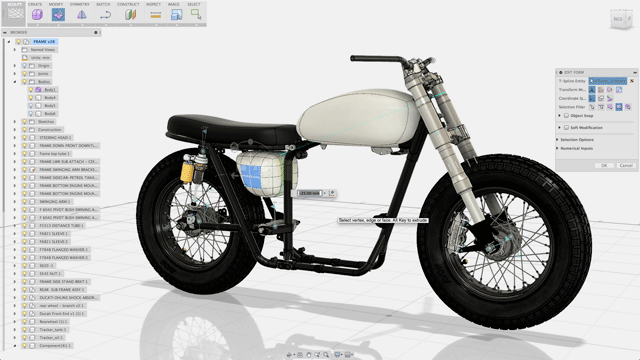

The tweaked interface now combines solid and t-splines modelling into a single toolbar

It began as a technology preview on Autodesk Labs, offering Autodesk’s take on the direct modelling movement. Partly an experiment to see how its community of users would use such tools, and partly a reaction against the (at least then) new moves from SpaceClaim and Siemens in that direction. It was delivered as a traditional software system — download, install, go.

Then somewhere along the line, things changed. Fusion became part of Autodesk’s cloud-based plans and the future of the system became the core of the company’s 360 initiative.

This saw a combination of cloud-enabled software that uses the cloud to do what it does best — centralise data, enable project collaboration and, in a few cases, improve computation capability.

Launching two years ago, Fusion 360 has become one of the most interesting systems to watch develop. It’s been done very publicly, rather than with beta software behind closed doors and NDAs.

It’s also moved on rapidly from offering direct modelling for solids to bringing together t-splines technology for organic and complex form design. Recently, it has moved on even further with history and parametric based modelling as well as CAM and now 2D drawing-based documentation.

What has also become apparent to us at DEVELOP3D is that while cloud-based services get over some of the issues associated with large scale deployment of traditional software updates, in that the application auto-updates and streams the latest release as it becomes available, it does raise a problem that has yet to be addressed.

This problem centres on the fact that, because there’s no large install and update time line, users don’t keep up to date with the progress made.

Although the software updates every couple of months, the user quickly settles into the habit of using it as they always have, without looking into new additions.

It’s a prevalent problem in all software, but the cloud delivery model exacerbates it greatly. So, with this review we’ll step through where things are at for Fusion 360 and look at what’s been added to the system that may have been missed in the intervening months.

Fusion 360 – Cloud delivery + Local

At its core level, Fusion 360 is all about the cloud and using the power of centralised data management and computation to enable teams to work together. The reality is that the system isn’t a pure cloud, browser based system.

As with all such systems, there’s a local install, but not in the traditional sense. Rather, when the user logs-in to the system, the local client is streamed and installed on their machine. Then, whenever updates are rolled out, the same happens again, meaning that it’s always up to date.

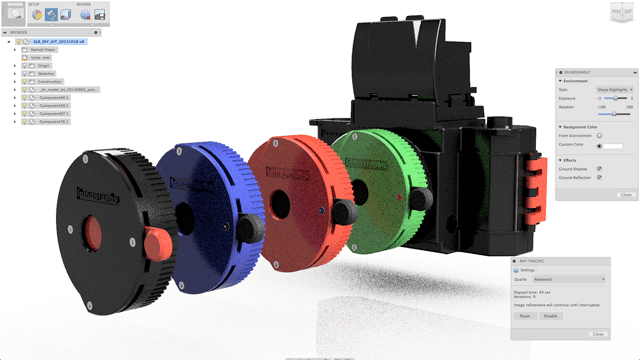

Fusion 360 now has a Rendering mode, an improved material library, and options for lighting environment combined with progressive ray tracing

The cloud benefits of Fusion is that all the data is kept on the cloud. This extends out from design related data created in Fusion to other project documentation — whether that’s MSDSs, project requirements, standards etc.

While for those working in the same location, on the same workstation, day in and day out, adding the weight of web-based storage might seem a little counter productive, but it doesn’t take much to realise the potential.

As soon as the user switches to another machine (be that a Windows PC or a Mac), all the data is there and, after a quick download, so is the software.

Even when bouncing between, perhaps, the workshop or shopfloor and the design office, or working off-site at a customer or in the field, this can be powerful. And once you’ve got used to it, it seems natural.

The introduction of intelligent handling of loss of internet connectivity also makes this more usable. While there’s no hard switch to enter offline mode, recent data can still be accessed and new data created from scratch. The system then simply resynchronises it to the project when its back online.

Fusion 360 – Direct editing

Fusion started off as an experiment in direct modelling and what it has become is something much more than that. While many of these tools are not making their way into the desktop Inventor system, the tools in Fusion are growing and maturing.

They cover most of the bases you’d expect. Push and pulling geometry, whether from scratch built geometry (using a mix of direct edits and sketching) or with third party, dumb geometry. It’ll read in data from most of the leading systems out there or use one of the usual routes, including STEP or IGES.

The Projects tab has been completely reworked and is much clearer

There are some interesting things that happen when native geometry is imported that are worth noting. For example, if a SolidWorks part has threads defined, the system gives the option to hard model them in, according to their specification. This is something that even SolidWorks can’t do natively.

Alongside the solid direct edits, Fusion also includes a ‘patch’ environment. This serves a couple of purposes. The first is that while it allows for the creation of surface geometry from scratch, it also enables the user to work with less than perfect data to repair, remodel and prep geometry for reuse.

If there’s anything missing from Fusion’s direct edit capabilities, it’s some of the tools that can be found in other systems, such as CoCreate and SpaceClaim. These tools enable users to rip geometry off one part of a model and reapply it elsewhere. While it’s not a big issue, it’s that kind of task that makes direct editing really sing in terms of usefulness.

Fusion 360 – T-splines and scuplt

Alongside the direct editing and match environments, Fusion has, for sometime, been gaining more and more power in terms of the definition of complex shapes.

This is powered by technology acquired when Autodesk bought out the t-splines organisation a few years back.

It’s a slightly different take on sub divisional modelling, which we won’t go into here, in that it allows users to direct with geometry in a very fluid and freeform manner to create organic and complex forms.

It’s best thought of as applying the same ease of use concept found in direct editing to the surfacing process — eschewing all the requirements of curves and surfaces in favour of pushing and pulling.

Curvature continuity is maintained where needed and it allows the user a great deal of control over how and where the geometry is edited, whether on a global scale to the whole set or using edges, vertices or face sets at a more local level.

Solving the direct edit paradox

So, up until the last big update, Fusion was centred on the two things we’ve discussed: direct editing and t-splines based organic form design. The paradox is that while both of these are incredibly useful tools, they do have one big issue in that if you progress a model too far, you can very quickly become stuck.

Taking the example of t-splines, a form can be modelled with as much detail and control as you want but the chances are you’ll then need to convert that form to a solid or surface model and take it through the engineering and detailing process.

The issue with Fusion was that once you converted your lovely t-splines model to a B-rep model, you essentially locked it down from any further tweaks, edits or changes. The same is true of many direct editing operations.

While for small, demo parts, it’s simple to change values, push and pull faces — the fact is that once more detail is added in, it becomes more difficult to go back and edit earlier created forms.

Taking an electronics housing project — design the form in t-splines, then convert it to a solid and shell it. At this point, you could probably step back, edit the source, reconvert and reshell it. But once mounting bosses, assembly features and such have been added in, you’re pretty much stuffed.

This is the reason that direct editing of geometry, while nice to have, can’t really cut the mustard on its own.

History + parametrics

Perhaps the biggest change since its launch is that the last few releases have seen Fusion’s approach to history-based modelling start to be introduced and fine tuned.

Experienced users of existing tools (Inventor, SolidWorks et al), will find that Fusion works a little differently. The basics are the same, with each activity performed on the model being componentised and listed in a history, but presentation differs in that the ‘list’ is horizontal across the bottom of the screen.

It also differs slightly in how it’s used. What Autodesk has done is split out the part and assembly portion, which is traditionally on the left of the user interface. The history of the development of those parts and sub assemblies is then located across the bottom.

Interestingly, there is a full set of tools that relate to this history. The model can be rolled back, specific points in the past edited and the model then updated.

It can also just be turned off — something I found rather handy when tracking history and realising that you don’t actually need it.

The last few releases also saw the introduction of parametric modelling, so that equations and logic can start to be introduced into models. Of course, these are also powerful when combined with the history tracking.

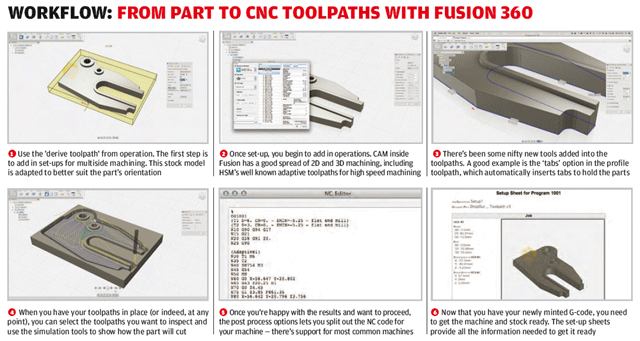

CAM for fusion 360

In the most recent update, Autodesk has, in addition to the modelling tools, started to bring its CAM 360 initiative into the Fusion platform. This has been beta tested as a separate 360 deliverable for some time and sees greater integration between the modelling and NC toolpath generation.

Essentially, you can use the modelling tools to create a part or extract it from an existing assembly and use the Derive NC toolpath from part operation to kick off the CAM programming workflow. This will create a new project item and the process can begin.

While we won’t go into too many details here, to get you up to speed, CAM for Fusion 360 now includes both 2D and 3D machining and has a pretty extensive set of operations from the HSMWorks stable, which Autodesk acquired a few years ago.

The set-up is created in terms of stock models, retract and safe heights. The user then works through the process of creating the individual operations, taking references from the model, adapting parameters and options where needed.

It has a good set of simulation tools, enabling users to see the resultant machined part, gauge material removal and see where operations need to be tweaked. Interestingly, if edits are made to the originating part, the system will update the toolpaths with a few clicks assuming no massive topology changes.

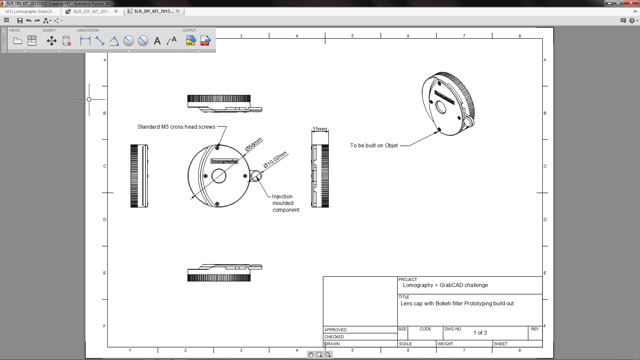

Fusion’s drawing creation tools are now in tech preview mode

Of course, if the part has had to be split out separately from the assembly, then it’s not quite as straightforward.

Sketching

The last item we’re going to cover in terms of updates is that Autodesk has also started to introduce drawing tools into the Fusion platform alongside the modelling and CAM functionality.

While the tools are rudimentary at the moment (it’s a preview), it shows that the company is looking to bring some of knowledge in documentation of design into Fusion.

The current preview of the tools allows users to lay out orthogonal views of a part and an iso metric view.

Dimensions (basics, linear, angular, radial and diameter etc.) as well as basic leaders and text can be added in. These can be output as DWG files or PDFs. As you’d expect, these are linked back to the originating data, so any updates will reflect in the drawings.

It’s also worth noting that these are, at present, only available on the Windows platform with Mac support to come in a later update.

Conclusion

The big question that many are asking is whether Fusion is ready for production use. The answer is, as you might imagine, it depends on your requirements and workflow.

Fusion is finding a home amongst small, typically start up companies, that don’t have the need to fully document design and engineering tasks. Such companies are looking to explore ideas and develop concepts beyond pure industrial design, and the toolset is developing to reflect that.

Will it replace traditional software? Again, it depends. At present, the tool set is powerful but it’s not going to replace all the bells and whistles of a traditional, workhorse CAD system.

There are also a lot of kinks that need to be worked out to make the system more efficient — the lack of ability to program CAM toolpaths off a part within an assembly, for instance. Also, at present, the user wouldn’t be able, to create a full set of engineering drawings to document the production of a part or set of parts.

If the user wants to layout quick views of a part or assembly, perhaps to assist with prototype build or to help with ordering parts, then it should do the job but, you’re not going to get a full GD&T drawing out of this thing yet.

The CAM tools are also developing nicely and while we’ve not yet cut metal with them, we will be soon and will keep you up to date with how it goes.

In terms of its cloud-based nature — the benefits of portable software, more flexible licensing and having centralised data, are huge once you start using it.

That’s of course, negated if the organisation doesn’t allow its use or the user doesn’t feel comfortable storing data in the cloud.

If you’ve not explored Autodesk Fusion lately, now is a good time as it’s developing nicely.

//www.youtube.com/embed/pozZzX0A-uM

| Product | Fusion360 |

|---|---|

| Company name | Autodesk |

| Price | $40 per month / $300 per annum |