The BTCC races are exciting and action packed. Here a WSR Racing car takes a corner on two wheels

While Formula One might be seen as the pinnacle of motorsport it’s arguably not as exciting as other forms of motor racing. The British Touring Car Championship (BTCC) for instance which pits souped up versions of two litre road cars against each other. “A lot of people like touring cars because it’s action-packed and there’s a lot of overtaking,” smiles Drew Macdonald, senior engineer at West Surrey Racing (WSR).

The 2016 season was indeed action packed as WSR, which runs a BMW 125i M sport, was on track to retain the Drivers’ trophy until the very last race at Brands Hatch when it was just pipped to the post (or podium, rather) by the Honda Racing team. It did, however, receive both the Manufacturer’/Constructors’ and Teams’ trophy.

Founded in 1981 WSR started out in Formula 3 before moving to BTCC in 1996, which it has had much success with – evident by all the 100 or more trophies on display in its reception area that then spill over to a shelf lining the wall of the workshop.

The BTCC holds ten race meetings a year at circuits across England and Scotland from the first weekend in April to the last weekend of October. The 2016 season, the 59th edition of the BTCC, saw eleven manufacturers represented by 32 drivers (each team is allowed up to three cars per race).

A WSR Racing team photo taken at Brands Hatch in 2016 with the three cars and their drivers

Strict rules

Although the cars that compete in the BTCC are essentially highly modified versions of family cars, they do have to conform to the specification and classification for production based race cars as set out by the FIA (the FIA or Fédération Internationale de l’Automobileis the governing body of motor sport) and the championship organisers TOCA.

The aim of the classification is to allow more manufacturers to race by reducing the design, build and running costs of the cars and engines.

As a result, some areas are fixed such as the weight, dimensions and frame of the car along with various parts, such as the wishbone, roll cage, front and rear suspension and most of the transmission. But then with the ‘free’ areas it’s up to the various teams as to how they design them.

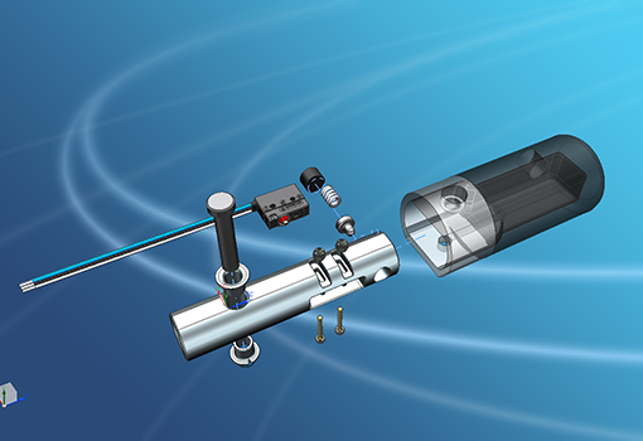

“The bodywork and everything in the chassis including the pilot’s seat, the tank, the ducting and the way in which parts are mounted is free as is the gearshift, steering column and the engine,” explains Macdonald.

There is a championship engine but WSR choose to run its own BMW engine, which starts out as a naturally aspirated roadcar engine and is then modified into a bespoke turbo charged race engine.

Macdonald and his team then design all the ancillaries for the engine and intercooler including all the pipework and ducting.

“In motorsport, aerodynamics is paramount – trying to get the most downforce for the least drag. The engine development is a key area and designing the best ductwork and cooling can make a big difference to the performance.”

Of course, just as aerodynamics is key in racing so is weight and a key consideration during the design phase is to create parts and components that are as lightweight as possible so that the ballast can be put in specific locations to bring the car up to the minimum weight limit.

In addition to this ballast the championship works on a success ballast system. This means that the leading teams are assigned success ballasts to act as a handicap, which has to go in a set position meaning that the team’s own ballast must be relocated.

“The ballast is to try and equalise the driver/car performance and make the racing closer and more exciting.

The ballast goes from 75kg for first down to 9kg for tenth position. If you are outside the top 10 then you don’t carry an additional ballast,” describes Macdonald.

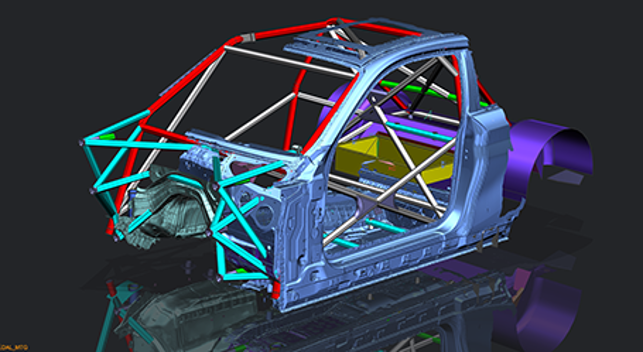

A Siemens NX CAD file of the chassis and roll cage

Scanning the body shell

The process of turning a road car into a racing car starts with getting a body shell of the BMW 1 Series.

“The body shell literally gets plucked off the production line, a bodyin-white with nothing fitted to it. We then send it off to a supplier to get all the primer off and to remove the acoustic foam, which takes a lot of the weight out,” he explains.

BMW don’t supply any CAD data so in order to get the information into its Siemens NX CAD tool, WSR cut the shell apart and scan in the shapes with a laser scanner.

This point cloud data is then brought into NX where it gets rendered into a surface. Only now can the design and development of the roll cage and all the many parts and components begin.

“There are lots of tiny brackets and bushes that have to get welded into the car to mount controls, battery mountings, harness mountings, seat belt mountings etc. It’s a huge CAD file with eight major assemblies including the chassis, roll cage, cockpit layout, transmission, engine, bodywork, front suspension and rear suspension as well as numerous smaller assemblies,” says Macdonald.

But this whole process isn’t done each season as shells are only replaced every five years or so and the above took place in winter 2012. Each winter since the design team have been working on the design of new parts in order to improve the performance of the car.

“In each winter since we look at the areas of the car that we think we can improve – bodywork, ductwork, pipework for air and water etc.,” says Macdonald.

But there are rules as to how much can be changed and each change has to be approved by TOCA. “It’s to stop the BTCC being like F1 where teams turn up with something different each race and therefore gain an advantage over the competitors and also exceed the budgets allocated.”

WSR’s recent investment in a new AMD graphics card helps to speed up the process of loading and manipulating complex assemblies

Hardware update

In the design office, the engineers have been benefitting from an update to their workstations. However, they did benefit from a new AMD FirePro W7100 professional graphics card with 8GB of GDDR5 memory, which was installed on Macdonald’s desktop computer.

Loading and manipulating large assemblies does really challenge graphical processing and with the new card Macdonald could see a noticeable difference in performance. “I like being able to keep all parts turned on but in translucent mode so that I can see right through the assembly, then I switch certain parts to solid when I am working with them. This was possible previously but it was very clunky. Now there is no waiting around,” he says.

WSR also invested in new event workstations, which also include the AMD FirePro W7100 graphics cards, for the data engineers to use on the trackside during race weekends.

“It used to take several seconds to download critical data from the wheels and damping but now we get high resolution results instantly and so we have extra time to make key adjustments. Such fine tuning can often make all the difference for the qualifying session and the race itself,” says Macdonald.

Dick Bennetts (WSR team principal) noting down laptimes at Brands Hatch

Winters are busy

Winter is a busy time for the WSR design and engineering team and for the 2016 season quite a few changes were made to the cars.

The first was a facelift to the bodywork, which was in line with the changes BMW made to its 1 Series that year.

For the 2016 season the FIA also introduced higher standards for the seat. This meant that WSR had to purchase new seats from its seat manufacturer Cobra, which also supplied the CAD data as WSR needs to bring it into its own assembly as the seat is bolted to the roll cage.

“It presents a bit of an engineering nightmare because each of our three drivers prefer different positions and angles for their seat and they are also different heights. So we had to come up with a way of making sure that the seat bracket accommodated all the different positions the drivers wanted and also ensure that the bracket that went onto the seat tube stayed roughly in the same place all the time. Then, once the seat brackets had been approved by our drivers, they then have to be homologated by the FIA,” he explains.

The last major change for the 2016 season was to the suspension. The BTCC has controlled suspension, which essentially means that its one of the features of the car that is fixed and is provided to all the teams.

Engineering company RML group was awarded a contract last year to provide the upgrade kit, which includes changes to the power steering, suspension and subframes.

In order to fit this full upgrade kit to its cars,WSR had to redesign certain aspects to make it fit.

“RML provide us with the NX CAD data and although we aren’t allowed to modify the components, we use the CAD to understand suspension better and the various options available for suspension geometry and to package our parts around theirs,” says Macdonald.

Rob Collard winning at Croft, Yorkshire, in 2016

As for this winter, Macdonald and his team are currently hard at work designing new parts for the 2017 season including more bodywork and cooling updates.

The aim is to have the cars ready for mid-February, which doesn’t leave them that much time for development. And having more time is one of the biggest challenges when working in this type of environment.

“You could spend all winter on one component if you wanted to. In F1 that is why they have so many designers working on the car because the longer you can spend the better the component will be.

“I have been doing design for 18 years and the longer you can spend designing a part – a. you can guarantee it will be right first time and b. you’ll come up with a better solution because with limited time you can draw something and it’ll do the job but it may not be the best way to do the job. So, it’s about getting the balance of fit for purpose, performance and the time it takes to get the part produced,” comments Macdonald.

With very little machinery in the workshop, the production of most of WSR’s parts is outsourced to suppliers such as Buckingham-based Freeform Technology, which assists in the production of the tooling and the manufacture of composite parts.

Then, once the parts arrive back into the workshop, they need to be fitted to the cars and tested before they get onto the race track.

Of course, WSR is aiming for more trophies in the 2017 season and Macdonald and the team are hard at work ensuring that the cars will be on track to reach this. “The reason why I have been an engineer in motorsport for so long is that it appeals to my competitive nature,” he grins.

West Surrey Racing takes BMW from the road to the race track

Default