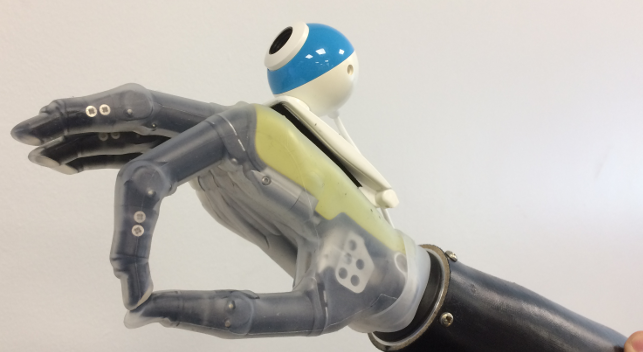

Ben Ryan and his son Sol, who is wearing the customised 3D printed hydraulic prosthetic which Ryan developed specifically for him

Helping hand

Ben Ryan is the inventor of Ambionics – a fully-functioning 3D printed hydraulic prosthetic – which he specifically created for his two-year-old son, Sol. However, a year ago he would not have referred to himself as an inventor let alone a designer or engineer or even someone familiar with the product development process. However, circumstances necessitated that he did and he embarked on a huge learning curve.

When Sol was born in March 2015, complications resulted in the amputation of his lower left arm. As a psychology teacher at the time, Ryan carried out research and discovered that children not fitted with a functional hand until after they’re two years old tend to reject prosthetics. This was an issue as Sol would have to wait for three years for a myoelectric prosthetic from the NHS. So Ryan decided to act.

“This time last year I had never used CAD and knew nothing of manufacturing techniques. Like everyone else I had heard about 3D scanning and 3D printing but that was about it. It was early July 2016 when I first downloaded Autodesk Fusion 360 and began to play around with the workflows.

“My approach at that time was to use an Xbox 360 Kinect scanner to create STL files of Sol’s NHS socket. I was chopping these up in Fusion, adding hydraulics and moving parts but I couldn’t get it to work.”

In December he reached out to Autodesk and was put in touch with Paul Sohi, a product designer at Autodesk in London.

“Paul showed me a really neat workflow for modelling sockets from a scan of the arm – a mere hour of his time led to a step change in what I was able to do – life changing really. I modified Paul’s workflow and was subsequently able to 3D print hydraulic actuators on a Stratasys Connex 3D printer that were perfectly modelled to the contours of Sol’s arm.”

Ambionics embarked on its first crowdfunding campaign earlier this year, the funding of which has enabled it to start a beta trial in which 20 passive arms were given away to babies and infants.

In the meantime, Ryan is back in the prototyping hot seat. “My brother and I are prototyping the manual and power assisted hydraulic arms ahead of the patent deadline.

We had a major breakthrough recently. Thanks to the new polymer from Stratasys – Agilus30 – we now have the first working double acting hydraulic bellow for bench testing with a 5psi micro pump and sensors.

This will be for when Sol is a little older. I’m hoping it will lead to a greater readiness for Sol to use something like the Luke Hand, which is undoubtedly the coolest project around.”

A team at Newcastle University have developed an ‘intuitive’ hand that can react without thinking

Hand that sees

Prosthetic limbs which will allow the wearer to reach for objects automatically are currently in development and soon to be trialled.

Led by biomedical engineers at Newcastle University and funded by the Engineering and Physical Sciences Research Council, the bionic hand is fitted with a camera which instantaneously takes a picture of the object in front of it, assesses its shape and size and triggers a series of movements in the hand.

Dr Kianoush Nazarpour, a senior lecturer in Biomedical Engineering at Newcastle University, explains: “Prosthetic limbs have changed very little in the past 100 years – the design is much better and the materials are lighter weight and more durable but they still work in the same way. Using computer vision, we have developed a bionic hand which can respond automatically.

“Responsiveness has been one of the main barriers to artificial limbs. For many amputees the reference point is their healthy arm or leg so prosthetics seem slow and cumbersome in comparison.”

A number of amputees have already trialled this ‘hands with eyes’ and now the Newcastle University team are working with Newcastle upon Tyne Hospitals NHS Foundation Trust to offer it to patients at Newcastle’s Freeman Hospital.

MYO is a university degree project that features customisable covers to enable users to express their individuality

Personal touch

When an amputee is fixed with a myoelectric prosthetic they control this artificial limb with the electrical signals generated naturally by their own muscles. However, extortionate costs mean these prosthetics cannot be supplied through the NHS.

Isobel Billau, a product design engineering student at Brunel University London, decided to tackle this issue in her final year project. Using minimal components would not only ease assembly and cut weight but would also reduce cost.

Fortuitously, a former graduate Ben Armstrong had already been addressing this in his MYO project and Billau decided to further his work.

“Ben left the project in quite a theoretical stage – he had the mechanism of the elbow moving but never received the components and had it tested. I have changed some of the components to reduce the prosthetic by about 50 per cent,” she explains.

Billau designed her components in SolidWorks and then 3D printed them on the university’s in-house Stratasys Dimension Elite printer using ABS. She then used laser cutting for the customisable covers.

Billau and her fellow design engineering students will be showcasing their final year projects at Made in Brunel from 15 – 18 June in London.

A look at three very different prosthetic arm projects

Default