Like most children, Milo loves to play sport. His favourite game is football, but at one time, he had to spend a great deal of time watching from the sidelines.

Having cerebral palsy means Milo wears an anklefoot orthosis (or AFO), a brace designed to support the ankle and to hold the foot in the correct position.

Wearing a heavy, cumbersome AFO, it’s hardly surprising that he has struggled to stay active on the pitch for extended periods without getting tired – but today, that’s all changed.

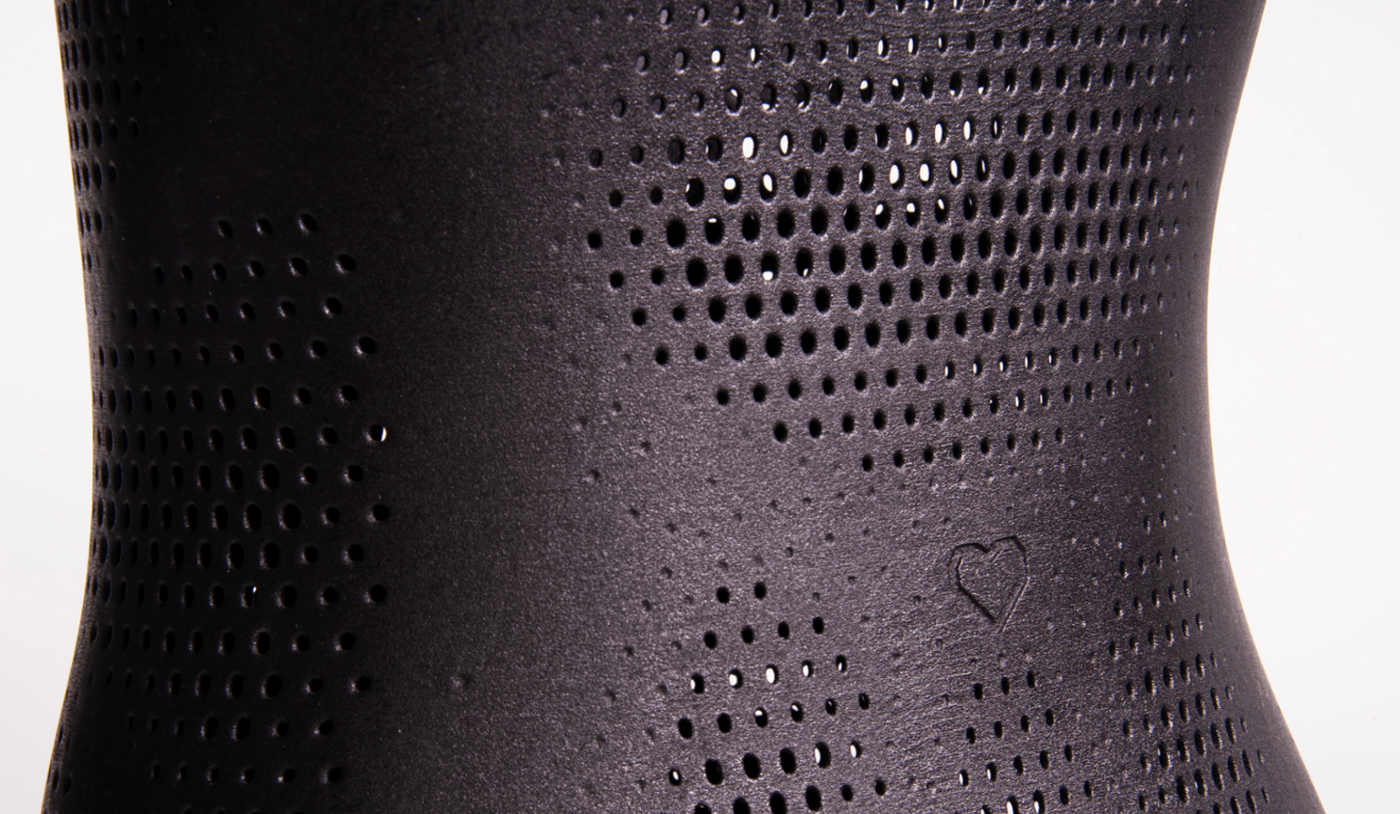

He has a new customised and 3D-printed AFO from London-based healthcare technology company Andiamo that is thinner, lighter and fits comfortably inside his football boot, giving him the freedom to keep playing as long as he likes.

Andiamo set out in 2014 to build a platform that utilises artificial intelligence (AI), 3D scanning, simulation and 3D printing to deliver custom-made orthoses to children with conditions such as cerebral palsy, spina bifida and scoliosis.

Using advanced technology enables the company to deliver orthoses with significantly improved functionality and at a lower cost, when compared to those built using more established processes.

While the technology is certainly exciting, for the team at Andiamo, it’s more about what that technology allows the company to deliver in terms of life-changing outcomes for patients and their families.

That’s the real driving force behind the company, says Andiamo co-founder Naveed Parvez, although even he concedes: “Sometimes we’re so focused on the shiny technical stuff, we miss the really important human stuff that these things have an impact on.”

Parvez speaks from personal experience. In 2003, following a difficult birth, his son Diamo was diagnosed with cerebral palsy.

This caused severe developmental delay and required Diamo to wear multiple orthoses to support his limbs and posture, and assist with basic functions. Creating these orthoses was extremely stressful for the little boy and his family.

“Diamo hated the process of having to be pinned down and wrapped in cold, wet plaster, which is an awful process for anybody, but even more so for a child who’s noncommunicative and doesn’t really understand what’s going on,” Parvez recalls.

“The plaster is then cut off and sent for fabrication, where the orthotic device is hand-manufactured based on the plaster mould. The whole process took a long time and we had an ongoing problem where Diamo would have outgrown it by the time it arrived back.”

3D printing potential

With his wife Samiya being Diamo’s full-time carer, Parvez resolved to find a better solution that would make life easier not only for Diamo, but also the whole family.

He began looking into the potential of 3D printing and its promise to deliver mass customisation. In 2012, however, Diamo passed away very suddenly.

“A year later, I happened to be at a technology conference where I saw someone 3D-scan an old steam train and then 3D-print metal replacement parts for it,” says Parvez.

“I realised that the technology had really moved on and surely now it would be possible to apply this in the medical world to 3D-print polymer orthotics for children.”

That same night, Naveed and Samiya registered their new company, with the aim of revolutionising the children’s orthotics industry.

They chose the name Andiamo, neatly combining their late son’s name with the Italian phrase for ‘Let’s go’.

Parvez admits that, at first, it was a crazy idea. Neither he nor Samiya had any experience of 3D printing a device – but their ambition went well beyond simply devising a technology solution to tackle a medical problem.

Their goal was to understand the whole environment of the patient and use this information to help them deliver a solution that not only fit the patient’s body and was comfortable to wear on a daily basis, but also improved their quality of life and that of their family members.

Following a successful crowdfunding campaign in 2014, the couple raised £60,000 to launch Andiamo in the UK.

But their aim was for it to be a global solution, so as well as hoping to partner with the NHS in the UK, they also wanted their solution to scale.

“In early 2015, we were introduced to Altair,” says Parvez. “By that point, we had spoken to loads of people, most of whom didn’t know how we would achieve it, but five minutes into the meeting, they got it.

They just immediately understood what we were trying to achieve and said, ‘Of course you can mass customise. Of course you can optimise every single device’.”

Martin Kemp, global practice leader at Altair, was an attendee at this initial meeting.

For him, the really interesting aspect of this project is how it combines a great deal of clinical information about the individual patient with additional information about what’s happening in the field, using it to inform the design process.

“Naveed’s initiative was to do some structured scientific learning around a very focused thing.

He wanted to take the guesswork out of the process to find proof and evidence of how the device will behave,” he says.

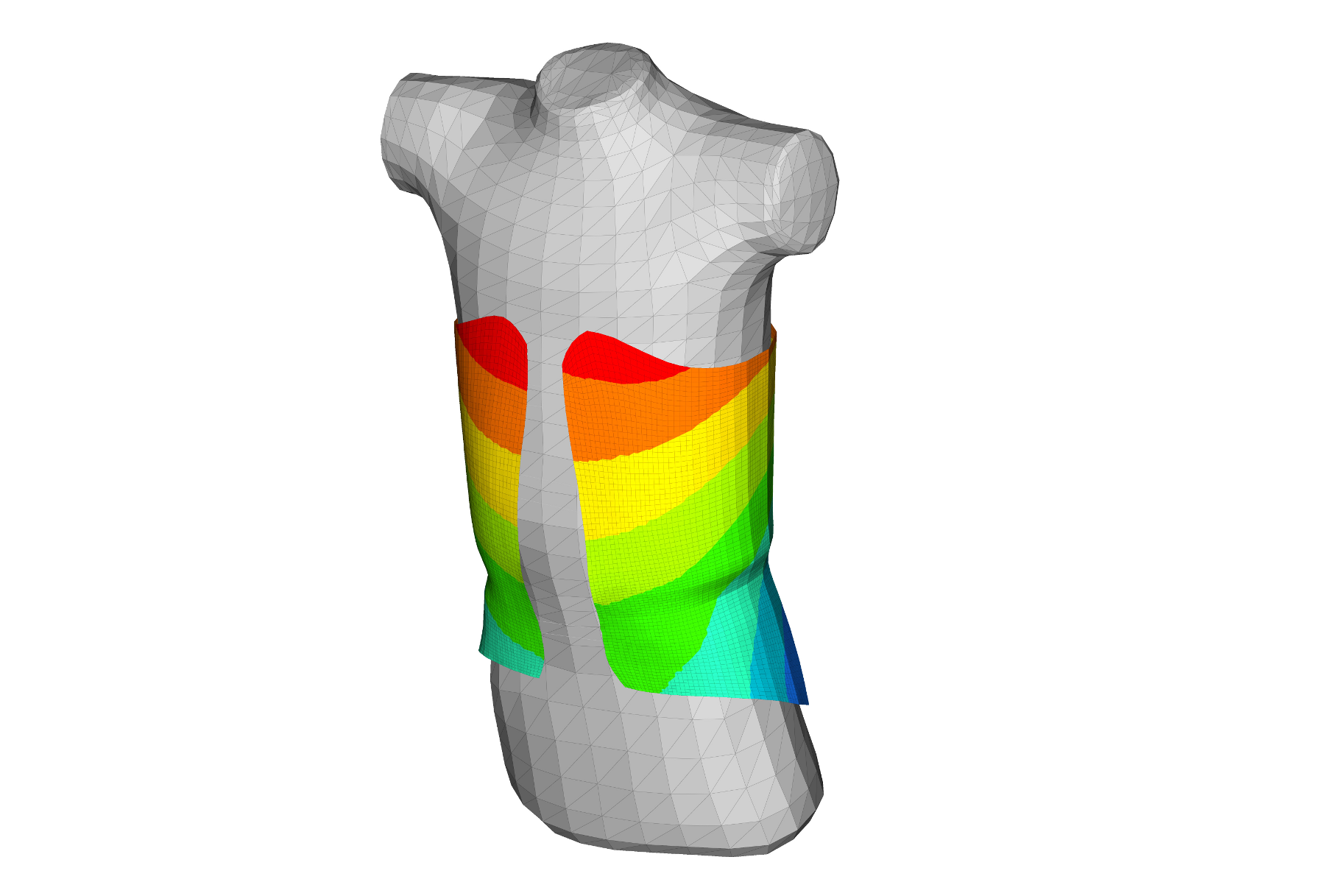

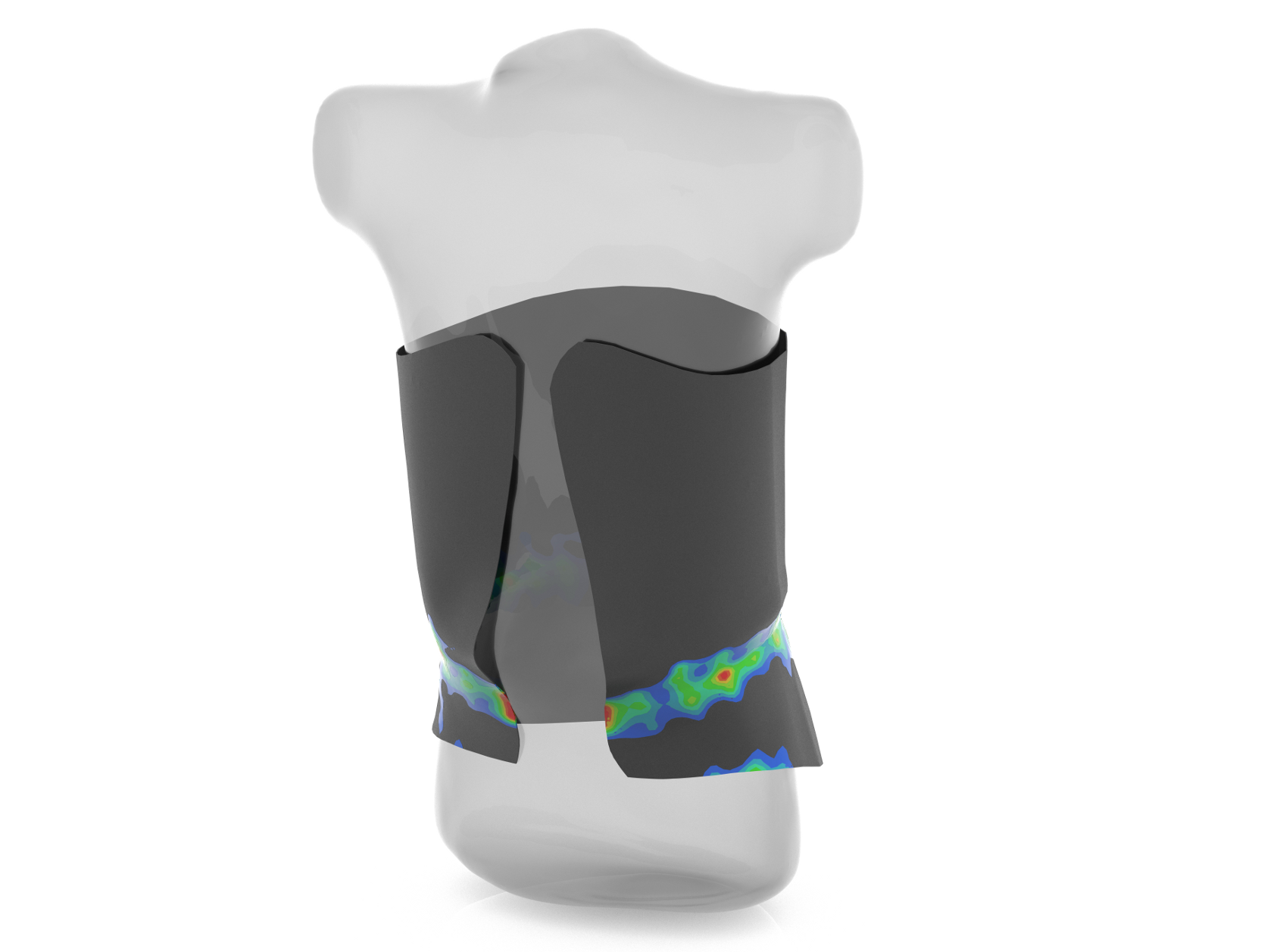

“By modelling the human body and then modelling the external structure of the orthosis, with all its stiffness and pre-tensioning, and then capturing the behaviour of the two together, [we would be able] to predictably prevent designs that aren’t performing well and that cause bruising and discomfort.”

Andiamo’s vision was to develop a software platform that rapidly standardises the patient’s information and turns it into a file that could be 3D-printed.

“The process can be divided into two parts. One is the generation of geometry, given the scanned data of the patient. And the other is the generation of an efficient structure to represent that geometry,” explains Kemp.

“So our first engagement with Andiamo was [focused on] the process of bridging that gap effectively to take the scanned data from the patient, together with Andiamo’s guidance and knowledge on translation of the patient’s prescription, to create some structural requirements.

So fairly quickly it becomes a structural design problem.” He adds: “The missing piece in that is how the human body interacts with the conceptual structure initially through to the final structure.

In the first instance, we worked on an ankle-foot orthosis and the problem there was defining some patient usage loads, converting an initial templatised geometry down into a parameterised structural model and putting those loads on the model and then deriving thickness distribution and reshape of that structure to fit the prescription for the patient.”

Optimising the design

In these early days of developing Andiamo’s process, there was also a lot of correlation work that needed to be performed to make sure what they were doing matched real-world data and, most importantly, that real-world measurements would equate to and correlate with personal experience.

“So when something’s uncomfortable, what is the metric to understand that and have we correlated that against some real-world measurements?

It’s how you define these ongoing monitoring exercises about how well the device is working out in the field. There was quite a lot of work involved in getting to that point,” says Kemp.

Once all that simulation is complete, the geometry is then optimised.

Here, Altair uses a range of optimisation technologies, including topology and free-sizing optimisation, which defines thickness distribution, in order to introduce strength where it is needed and so create an optimal design for 3D printing.

While it might seem as though it would take a long time to perform all these simulations, Andiamo has developed a process that takes just two hours from when the data enters the platform to when the 3D printed file emerges, and Parvez says that a real-time process is now on the horizon.

For the patient, the process begins with a 30- to 40-minute assessment with the clinician, where a prescription is filled out.

This includes the 3D scan data, which takes about five minutes, as well as, where applicable, any photos and videos.

This prescription then goes into this standardised platform where Andiamo’s engineers create a CAD model.

This file is then transferred into Altair HyperWorks, where Optistruct and Radioss are used to simulate and optimise the design to meet the necessary clinical requirements and patient needs.

Two hours later, the clinician signs off the design and the file is sent off for 3D printing. Andiamo uses a network of 3D printing bureaus and the technology predominantly used is EOS powder bed systems, which produce the orthosis in Nylon 12.

“At the moment, our average turnaround time from the beginning to end is 13 days and will be a week or less soon,” says Parvez.

“We know that in theory, using current technology, that turnaround time could go down even more. So, at the moment, it’s not the design that becomes the problem. It’s the physical manufacturing that causes a blockage.”

When the orthosis arrives back from the bureau, the patient comes in to have it fitted.

So confident is Andiamo in its process that it guarantees a 100% first-time fit, so there’s no need for another appointment until the child outgrows the device.

A beautiful failure

Of course, the journey for Andiamo hasn’t been completely smooth.

Developing this process and getting it up and running has come with challenges, particularly around the amount of material used in an orthosis.

As Parvez says, clinicians didn’t realise initially how much difference saving just a few grams could make.

“We want to make the device as light as possible, because every gram it’s heavier, it’s extra effort for the child. So we are dealing with quite fine tolerances between safety and really trying to enable them,” he says.

A particular incident illustrates this point well, which Parvez describes as a “beautiful failure”.

Football-loving Milo actually broke his original orthosis, due to a fault that could be attributed to just 13 grams of powder. That’s how narrow the margin is between success and failure.

As Parvez explains: “Milo was part of our initial trials, and when we investigated what happened, we realised that it wasn’t the FEA model that was the problem. The design was fine and the parameters that we put into it were correct.

The problem was the mental model of everybody involved in that decision.”

He continues: “We limited him. We assumed that he had a certain level and wouldn’t go above it, and at no point during that clinical assessment did we ask, ‘What if he exceeds our expectations?’ Of course, he did – by playing football.

That information then fed back into our simulation platform to make sure that those metrics are included as part of the process.”

Andiamo is also now working on embedding sensors into its devices, in order to better understand their use by the wearer and how the design performs in the real world.

“It’s early days, but what we believe it will do is start to point towards better devices, better design and better intervention as well,” says Parvez.

“Most people automatically assume that it’s when things go wrong that you need to intervene, [but] you need to intervene when things go right.

There are absolutely situations where someone over-achieves what you expected, like Milo, and you need to keep them on that upward trajectory and intervene earlier,” he continues.

“Right now, appointments are based on a ‘finger in the air’ estimate that helps with scheduling, but actually, there is a whole new model of healthcare out there that is possible when you combine all of this together.”

In October 2019, Andiamo opened its own R&D clinic in London where it sees patients. The ambition now is to work with the NHS and make this service accessible to everyone.

“We’ve just completed a two-year project with Barts Health NHS Trust on the feasibility of implementing this in the NHS. We are waiting for the peer review of that research, but early indications point to a very positive outcome,” says Parvez.

Andiamo may have lofty goals of revolutionising the orthotics industry around the world, but it’s understanding the impact this could have on families, based on first-hand experience, that provides all the motivation this husband and wife team needs to keep going.