Whitedot creates a small range of focussed freeride skis for skiing on piste, in powder and for backcountry exploration

Ask a skier what he or she loves about skiing and they’ll probably wax lyrical about the feeling of freedom in being in the big outdoors, the grandeur of the mountains, the sensation of carving into fresh powder, the exhilaration of burning down a slope and then, of course, the Après ski and hot tub soak at the end of it all.

“One of my favourite times to ski is when it’s absolutely dumping with snow and you can’t see your hand in front of your face. There is nobody else around and you are just skiing for yourself. It is really addictive,” describes Paul Jamieson, co-director and head of product design at UK ski manufacturer Whitedot.

“Blind ski conditions – I hear you,” interrupts his colleague Adam Gorrill with a smile, “but as the company ambassador I’d also like to highlight that we do positively promote safe skiing.

“We produce the tools that allow our customers to ski safely. They know their skis are going to perform and they can just get out there and seek out their desired freedom and enjoy the environment they are in.”

A UK manufacturer of skis might seem incongruous when the two things you need for skiing are snow and mountains, which the UK (bar Scotland) has very little of. However, as Gorrill points out, although he and Jamieson are British, and the company’s distribution hub is in Leeds, the idea for Whitedot was actually drummed up in 2007 in the French Alps, where they were both working at the time.

“Company founder Andrew Phyn, who was a distributor for skis, had always loved developing products from when he was a young lad in New Zealand and so he started designing skis. For three years Andrew just prototyped and tested his theory for the products and then in 2010 he brought together the five of us as company directors and we launched Whitedot commercially,” explains Gorrill.

Whitedot has two constructions for its skis — traditional and the Carbonlite series. In the latter, a blend of flax and carbon fibre replaces the fibre-glass layers resulting in a ski that is 25 per cent lighter and less susceptible to degradation

Whitedot – Starting point

Before 2010, Phyn was actually consulting with Jamieson, who has a vast knowledge of the ski industry having lived and breathed it every winter for the past 20 years. Starting out as a competitive skier in his teens, Jamieson became an instructor at ski resorts, moving on to fixing skis and then even had a hand in creating them.

“I have been involved with a number of ski companies over the years bringing products to market and although I’ve understudied ski designers before I never took on the role myself until Whitedot,” describes Jamieson.

“I think it’s one of those things that if you have a real passion for it then you spend the time learning and gaining knowledge. And skis are really interesting – they can get quite geeky and technical.”

But, unlike say a car that incorporates thousands of parts, how technical can a product that essentially consists of just one part be? Very, says Jamieson, and the reason being is that the variables are endless.

Arguably, the two most common words in any ski designer’s vocabulary are camber and rocker.

“When laid flat on the ground, if a ski touches the surface at the tip and tail with a gap in the middle, that is called camber. Essentially, the ski looks like a bow and when it is pressed in the middle it rebounds.

“You can also do the opposite. So the middle of the ski will touch the surface with the tip and tail rising up. This is called rocker,” he explains.

With increased camber there is a longer effective edge, which allows for more precision when carving turns as well as a more stable and controlled ride. Whilst, with increased rocker there is essentially zero effective edge but it does allow for great floatation in deep powder conditions.

As Jamieson says, there are countless variations between these two as well as other considerations such as the shape of the ski, its width, length, sidecut, edge angles, stiffness, materials, weight and so on. These are all determined by the type of skier and what the ski is being used for.

When Whitedot officially launched the team decided to focus on a small range of extremely high quality freeride skis that can handle everything from groomed slopes and fresh powder through to backcountry exploration.

All Whitedot skis are manufactured as a pair. This ensures that, having been exposed to the same conditions and processes within the factory, they will perform the same

On a mission

As with most products, the design process of a ski kicks off with market research. As well as consulting those in the ski industry, Whitedot also work with a team of professional skiers that ski all around the world.

“These guys will help me come up with a mission statement to nail down where we are going with a new product. A lot of the variables will be knocked off if you have a really good mission statement,” explains Jamieson.

This then leads onto the sketching side of things and here Jamieson will spend a fair amount of time creating line drawings. “I guess I work in a fairly old fashioned way with pen and paper. I also do quite a lot of photography work. For instance, in a new powder ski that is currently in development, I spent a lot of time looking at surfboards.

“Surfing is another passion of mine and I find that there is a lot of parallels with surfing. With this bigger ski, you’re effectively surfing it through really soft snow.”

Once the line drawing is complete and the dimensions finalised, it will be given to Whitedot’s Europe-based factory, which specialises in snow sports. Its engineers will then create the 3D CAD model in SolidWorks.

For Jamieson this handing over marks the most challenging aspect of the entire design process. “Designing skis is a constant challenge but for me personally the thing I find most difficult is signing off the design.

“You are constantly reevaluating and second guessing yourself because it might look fantastic on paper but ultimately you just don’t know until you get that first prototype mould onto the snow,” he confesses.

Even though the CAD model is being created by the factory, Jamieson is still very much involved. In fact, he will travel there and sit with the engineer for the majority of the time he does this. This ensures that the design intent is kept but equally that the product can be manufactured as it is or whether the design may need some tweaking.

“I am slowly learning the intricacies of CAD though I tend to leave this to the engineers at the factory because they have such detailed knowledge of their processes and need the information in specific ways. I have a great working relationship with them. We all know how each other works so it’s actually a pretty efficient process,” he says.

Austrian pro-skier Eva Walkner has achieved multiple podium places using her Whitedot skis including first place in both the 2015 and 2016 Freeride World Tour

Popular poplar

All of Whitedot’s skis feature a core that is CNC milled from both Poplar and Ash, which are vertically laminated and bonded together.

“Poplar remains an industry standard due to its durability and elasticity while Ash, as a hard wood, strategically placed under the bindings (for retention) gives unparalleled pop and strength,” describes Gorrill.

The core is sandwiched inside other materials and this depends on the construction method used, of which Whitedot has two.

A standard fibreglass construction and a lightweight construction for its Carbonlite models, which harnesses carbon fibre and flax.

“Flax is essentially linen and we started layering it within our construction in 2012 for its incredible dampening properties,” describes Gorrill.

The R.118 Ragnarok Carbonlite was designed for lightweight, all-access skiing

Designing the dots

In parallel to Jamieson working on the product design, Gorrill will be creating the graphic design as well as the brand messaging.

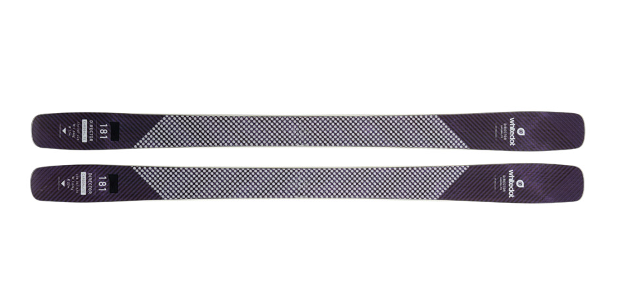

Each ski has its own distinct colour with Whitedot’s signature dotted wallpaper pattern on the top sheet, either in white or black depending on the type of construction.

“Our ethos has always been as simple as possible and I am a big ambassador of getting rid of clutter and information on products and using the space around to showcase the product’s highlights,” says Gorrill.

“The pattern also emphasises the ski’s shape, camber profile and its intended use.”

Whitedot encourages skiers to use their skis and ‘find their freedom’, but of course being responsible and safe whilst doing it

Put to the test

With the CAD model complete, the moulds will be commissioned. The factory will produce a few prototype skis, which will be handed out to Whitedot’s professional team of skiers who will put them through their paces on the slopes and then provide feedback.

As well as these professionals, Jamieson will take a pair for himself and test them too. “It’s the best bit of the design process,” he smiles.

It’s also crucial because, as he says, the designs might look perfect on the computer screen but may be far from perfect in the snow.

He cites an example in which a ski went through a fairly comprehensive design process but when it was put to the test on the pistes, it didn’t work.

“In the end, it was just an issue with the mounting points,” reveals Gorrill. “The bindings, which we thought had to be mounted at a certain place, needed to be 60mm back and as soon as we put it there the ski came alive.

“We had sacked it off in all fairness, but Paul was very persistent, spending six very uncomfortable weeks wearing them to figure out what the problem was.”

Jamieson adds, “You’ve got to work out where you’ve gone wrong to move forwards. I was pretty confident with that particular model and it was just a case of spending time reviewing and reevaluating the design.”

Director whitedot skis

Whitedot – Environnmentally aware

Once thoroughly tested and resulting changes made to the CAD file, the factory will commence manufacture. Realising that its product can’t be termed as eco-friendly due to the resins, fibres and metals that it is constructed out of, Whitedot does try, as Gorrill puts it, “to do our bit for the environment wherever possible.”

The wood is sourced from sustainable forests less than 30 miles from the factory, any wood off-cuts from the milling process is used to heat the factory and the excess fibre-glass is trimmed and passed on to a local concrete facility for up-cycling.

Unlike other ski manufacturing processes, Whitedot skis are also produced as a pair.

As well as each pair being CNC milled from the same Poplar and Ash laminated core, which ensures that they will perform and flex in the same way, they will then undergo the rest of the process together.

Once manufactured, the skis are sold through the website or via retailers. And spending all winter in the mountains themselves, Jamieson and Gorrill do enjoy spotting Whitedot skis being used on- and off-piste.

“I have totally chased people down the mountain before and collared them at the chair lift,” confesses Jamieson. “I don’t tell them that I designed their skis but just comment that I have a pair as well and do they enjoy them. It’s always a really cool conversation to have.”