Brooks Running, which celebrated its centenary last year, is a Seattle-based company that designs and markets running-specific performance footwear

Whether they plan to pound the pavement, road or trail, what every runner looks for in a running shoe is, above all, fit and comfort.

The look of the shoe plays a part too, of course, but Seattle-based sports apparel company Brooks Running is on a mission to help its customers ‘Run Happy’, so any shoe that led to friction, pain or injury – however aesthetically pleasing – would be a complete non-starter.

“We focus more on the functional standpoint, so everything that I do needs to fall through that filter. Functionality comes first, and then the aesthetic wraps around that,” explains Indra Gunasekara, senior footwear designer at the company.

The design process at Brooks Running begins with designers sketching their ideas in 2D – and it wasn’t so many years ago that their designs would stay in 2D for the duration of the product development process.

The lightweight Glycerin 13 is one of the latest technical running shoes to be launched by Brooks Running

But then in January 2011, Nick Martushev joined the company as design engineer and digital product creation manager, with a long track record in tooling and 3D design technologies. 3D, he says, was relatively new to the footwear industry when he started his career at Adidas some 17 years ago, but has made big progress since.

Still, he explains, the footwear design process continues to kick off in a pretty traditional way, with a physical, 3D representation of the human foot, known as a ‘last’:

“It is very difficult to design around this shape in 2D, because of the inherent asymmetrical and organic nature of it. It makes it virtually impossible to visualise the end product using this method,” says Martushev.

“In the past, footwear designers would create scale drawings that would then be faxed to the mould shop vendors in Asia. These scale drawings would then be used as templates for model shop workers, who would carve the designs into wood.”

This method had some problems, he adds: designs became subject to the modelmaker’s individual interpretation and many failed to grasp the designer’s concept, causing delays and affecting overall aesthetics.

“We’ve come a long way since then, with the advent of CAD/CAM, 3D modelling software and additive manufacturing. It’s really made our lives easier.”

At Adidas, the CAD tool chosen for 3D design was Rhino, which Martushev brought with him when he joined Brooks Running. In fact, he’s been a certified Rhino instructor for the past eight years.

“Rhino has its strength in surface modelling and was vital to the transition from 2D to 3D in our industry, due to its designer-friendly user interface and its no-nonsense approach to creating complex NURBS surfaces. That’s why I chose to continue to use Rhino as part of Brooks’ tooling design and engineering process. It just works,” he says.

“At that time, Rhino also didn’t have a lot of the restrictions that most other 3D software had with the boolean and parametric methods. It really gave us the freedom to build all the intricacies and freeform, organic surfaces that athletic footwear inherently has.”

3D visualisation on the starting blocks

Although Rhino is more than sufficient on the 3D modelling side, Brooks Running’s colour design team were still using 2D tools, particularly Adobe Illustrator, in their ideation process.

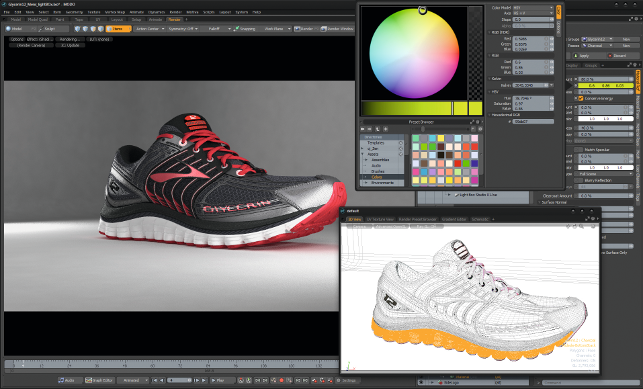

A MODO screen shot showing the Brooks Glycerin 12

Martushev felt that a 3D visualisation tool would help them, as material finishes are more realistically represented in 3D than they are in a flat 2D image. It would also allow them to experiment with ideas and create more iterations, by enabling them to select from a variety of finishes and colours.

“We are a premium footwear brand and a lot of the premium quality found in our footwear is in the materials, textiles, colours and sheens. We really wanted a way to dial in those aspects, from a virtual perspective, prior to us getting any completed physical samples back from our manufacturing partner,” he explains.

Not set on any particular 3D visualisation and rendering tool, Martushev took the advice of a freelance designer, who praised the powers of MODO from software developer The Foundry for its ease of use over other visualisation tools.

“He mentioned MODO and I had actually never heard of it. So, I beta-tested it for a little while and I really grew to love it. The user interface was a lot different to what I was used to, but it was intuitive and the learning curve was pretty quick. I also really loved the built-in rendering engine for its quality and speed, not to mention that it imports native Rhino files,” he says.

“It also definitely helped that the price was more affordable. We were looking at this software as a tool to be utilised by most of the design and engineering team for the long run so, from a financial standpoint, it just made sense.”

Introducing MODO

Martushev’s initial proposal to use MODO was met with hesitation by some members of the design team.

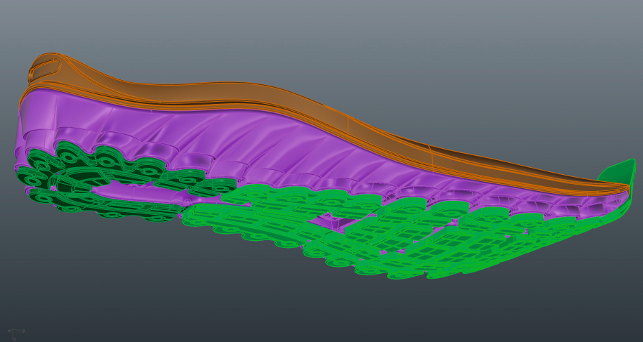

A Rhino screen shot showing the tooling or sole component of the Brooks Glycerin 13

They were put off by stories they had heard about the intricacies of learning 3D software, so he set about making the software as easy as possible for them to use as part of their footwear design process.

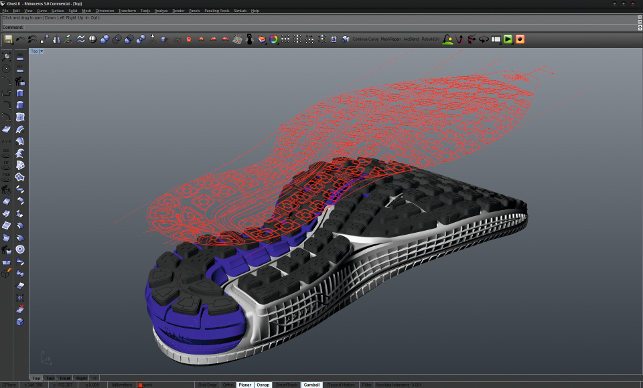

Essentially, a shoe is divided into two parts: first, the ‘sole’ or tooling component; and second, the ‘upper’ or textile component. On the tooling side, once the designers have completed their blueprint, which is essentially a mechanical drawing to scale, their design for a sole is sent off to the team based at Brooks’ manufacturing partner in Asia, where a surface model is constructed in Rhino.

This 3D file is sent back to the design team for review, but since the sole is where much of Brooks’ running technology can be found, this file may go through multiple iterations to get to exactly what designers want. As part of this process, 3D printing will be used to create prototypes for design and engineering investigation.

“Simultaneously, the designers have also been working on the shell pattern of the upper. I’ll then take that flattened pattern and apply it to the last using Modo’s UV tools,” Martushev explains.

Importing the Rhino-based sole files and combining them with the uppers, modelled in MODO, Martushev has devised a way of creating a template scene in MODO that houses the complete virtual shoe, so that designers can simply jump in and start applying materials and colours.

“For me as a designer, I am not too concerned with learning and knowing how to use the programme itself, I just want to use it to accomplish what I need to do,” says Gunasekara.

For further simplification, Martushev prepares files so that the design team has only to focus on two areas: the rendering viewport and the shader tree.

“They love the fact that they can just go into the render window, click on one of the overlays of our shoes and that material automatically highlights in the shader tree. They don’t have to go and look for it and they can manipulate the colour and the surface finish right there,” he says.

That came as a pleasant surprise to many of the more sceptical members of the design team, he adds: “They were colouring footwear within the first day of training.”

A Rhino screen shot showing the underneath of the sole component of the Brooks Ghost 8

Gunasekara, who has been designing Brooks Running shoes for the past 15 years, enjoys how MODO allows him to get creative, inspiring new ideas by enabling him to play with different colours, materials and finishes.

“Certainly when you look at a shoe, there is a lot of form language that exists and sometimes I use MODO to steer me in a certain direction or get an emotion around the product that I’d like to create,” he says.

“Also, instead of just exploring one option, MODO gives me the opportunity to explore, say, three options. That can be a huge resource.”

Many advantages

The biggest advantage of using MODO is its fast Nexus rendering engine, according to Martushev.

The instantaneous feedback it provides is very beneficial for designers investigating different colour combinations and surface finishes. “They don’t really want to be hindered by software and that’s why they really like MODO’s quick feedback,” he says.

The design process begins with the designers sketching their ideas in 2D

Another benefit is the user-friendly interface, which is easy to learn even for those unfamiliar with 3D software.

“Historically 3D software has always been difficult to use. You had to be a rocket scientist to figure out the user interfaces,” he jokes.

“But I think MODO has done a great job with revising their user interface to really accommodate the designer’s needs.”

MODO also saves time. From Gunasekara’s point of view, designers don’t have to spend as much time ordering samples of materials. They can often make a judgement based on the materials they see on the screen.

“I think one of the most important things as a designer is getting to a place where you are confident and comfortable in what you are delivering to the technical runner. Using MODO aids you in bringing that to reality faster,” he says.

Across the company, Brooks Running estimates that it has slashed around 30 per cent off its sample requirements by creating virtual footwear in 3D. Says Martushev: “We won’t completely eliminate the need for physical samples, because the sense of touch cannot be replicated, but in the interim, we can provide multiple colour and material options via 3D to the design team and other stakeholders, as opposed to wasting company resources to build physical samples that we may choose not to go to market with.”

In other words, the company wouldn’t make decisions solely based on the 3D visualisations, as they still want to have a physical sample to hold, look at and sign off. “But the few examples that we have done, we have actually compared a physical sample to our final rendered image and really most people couldn’t tell the difference,” Martushev says.

Navigating the final laps

Not every Brooks Running designer is using MODO yet, Gunasekara admits, but he expects more will use it in future.

Nick Martushev, digital product creation manager at Brooks Running

“If you know and have an understanding of what it takes to build a great technical running shoe, you can utilise MODO to take you three or four steps deeper, which really is an amazing thing,” he says.

“I’m excited to see what 3D can do for the designer – to explore things that they can’t necessarily come up with by themselves.”

Martushev, meanwhile, sees other uses for MODO at Brooks Running. It could be used as a marketing tool, for example, to display to customers interactive, 3D models of running shoes on the company’s own website or those of retailers.

“What we found within the industry is that a lot of runners are doing research online now prior to purchasing their shoes, so any additional tool that they can use to help make that decision easier would benefit both the consumer and the retailer,” he observes.

Ultimately, Brooks Running wants to ensure that the materials, colours and finishes it uses in its shoes are worthy competitors for the fit and comfort that already enable its customers to ‘Run Happy’. MODO is helping the company get the mix right.

Brooks Running creates a running shoe that competes on every level

Default