With the pandemic seeing a rise in home working, Shure set about designing a microphone capable of focussing in on its user, while looking chic on their desktop. Stephen Holmes spoke to the product team of the Shure MV5C to learn how it was developed

Working from home has become more prevalent across all industries, creating new challenges – from being heard over the sound of a washing machine spin cycle, to setting up an attractive desk space in the home.

Shure is a legendary brand in the field of microphones, with over 96 years of experience – from professional stadium performance kit to office equipment staples – and decided to tackle the problems being faced by home workers head-on with its latest product, the MV5C.

The MV5C microphone was designed to be a simple audio solution specifically for laptops and home-office use, explains John Born, Shure associate director of global product management.

The MV5C microphone was designed to be a simple audio solution specifically for laptops and home-office use, explains John Born, Shure associate director of global product management.

“We updated our firmware and the digital signal processing to give user’s the best speech, clarity and isolation right when they plug it into their laptops,” he says.

The microphone doesn’t require any other connection or configuration and it is compatible with both Mac and Windows operating systems.

Many of its high-end features are software based – elements like Speech Enhancement Mode help to isolate user’s voice and prioritise it over unwanted background noise – however the physical product development is far from an afterthought.

The aesthetics of the microphone had to stand out from the competition, while being attractive to a wide range of home workers in varying professions. Much like you wouldn’t wear a gaming headset bedecked with flashing LEDs to a high level board meeting, the MV5C had to channel style and quality, without being too buttoned-up.

The design team wanted to bring elements of Shure’s heritage and classic designs into the modern age to a simple to use, powerful audio solution that has a huge impact on the daily users’ lives.

“When we develop a new product design, we go through an extremely rigorous process of industrial design and competitive landscape explorations. We also analyse trends in colours and in the market. Then we distil the exploration phase down into a few targeted product opportunities,” says Born.

Different material, weight and size studies help shape the first concepts, testing button placement along with other mechanical elements. “Once we came up with the final version, we create 3D designs to bring the first physical and functional models to life ⎯ we deploy a lot of 3D models throughout those processes. The use of 3D [renders] and models was extremely useful to find and deliver the best version of our MV5C.”

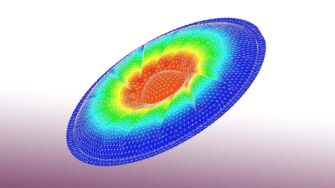

Rhino was used to create the design, allowing the design team to be flexible when deploying designs into different types of file structures. The mechanical engineering group also uses Siemens NX, which it uses to create a model for use with audio analysis tools.

“Within the acoustic lab and through these programs we make sure our microphone designs and elements will behave the way they are intended to,” explains Born. “We deploy countless hours of simulation work to ensure that these simulations and validations are constantly aligned.

“As the design gets more mature, we assure that it will pass several vibration tests, drop tests, moisture tests, or resistance tests without failure.”

By packing in as much virtual testing as possible, Shure is able to greatly reduce the length of the development process, “minimising the risk scope” early in a project.

Physical prototyping was also extremely important in validating acoustic and mechanical designs, with the design team deploying different processes and methods to make sure that acoustic discipline remained safe, no matter what was placed around the microphone – given the MV5C was likely to live on a cluttered office desk.

“Because we like to make good sounding products, we always need to find a constant balance between three disciplines: (prototyping) design, mechanics and acoustics,” says Born

3D printing has recently been used beyond prototyping purposes – being used within the production round. too. Shure explains that the move has given its engineering team more freedom to make structures that could never be made with traditional plastic tooling.

He adds that the biggest challenge they faced was resetting expectations in terms of timing when creating prototypes.

“Software rendering and 3D printing is so advanced today that sometimes you can look at something on the screen and print it right there. But the real working product doesn’t yet exist in the real world, and we need to manage expectations around that,” he says.

“What really changes the timeline is when prototyping becomes part of the production phase and in this way, you can make significant developments in terms of timing.

“When products can be 3D printed instead of tooled with plastic pieces, the whole reality and building process change, and we are getting very close to that.”

Recently, Shure has invested a significant amount of engineering resources into quality, testing and validation processes through its validation labs, embracing it to the point of even restructuring its headquarters.

“When we start a product, we need to ensure that it will meet the expectations and requirements of the customer and we make sure that it happens through the different tests,” says Born.

“When there aren’t tests, we develop them ourselves. This means that we could need new robots to test our headphones; buy new laser scanner to measure different parts, or even build a new vibration room to test how we ship packages.

“The great thing at Shure is that we don’t let a new test scare us away from always delivering the best product for our customer. Not only do we know exactly what we are building, but we also know how to test it, how to build it and how to develop it.”