Break your ideas down, recommends Jonathan Rowley of Digits2Widgets, because a bit of design thinking can go a long way to getting better results from today’s 3D printers

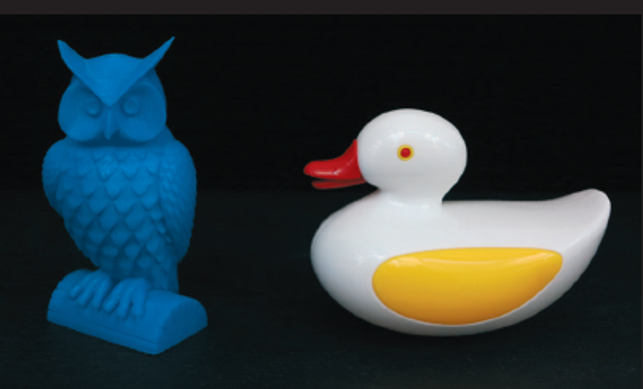

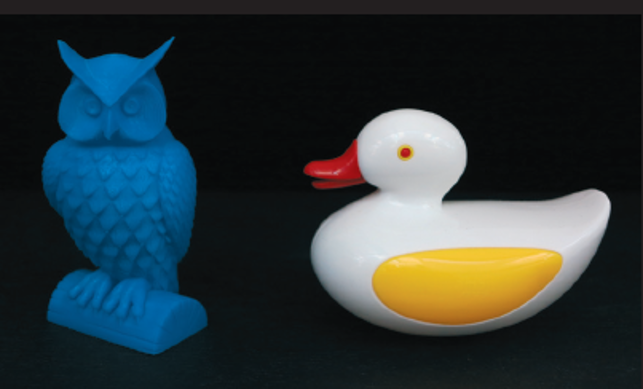

The Makerbot Owl and Ryland’s Bath Duck for Ambi Toys

Sales of desktop 3D printers have been driven by the claim that they will democratise the design and production of objects, all in one go. Anyone who has worked with them, however, quickly understands that the reality is a little different.

The limitation of nearly all 3D printers is that you are confined to working with single materials. If you want to produce anything more than a single-material, single-colour object, a great deal more work is required.

To this end, clients working with our industrial 3D printers often have to produce their objects as numerous separate components that are assembled later as a completed ‘whole’.

They might, for example, run up against limitations in terms of the size of the build chamber on a 3D printer, which dictates the size of objects that can be produced.

In order to produce larger objects, these objects need to be designed as a collection of parts that can be assembled once printed.

And in the world of industrial 3D printing, breaking down objects into components can also make design and production more affordable. If your object contains a lot of free space, then you’re effectively paying, in time and money, for a 3D printer to ‘make’ you nothing more than fresh air.

In order to avoid this situation, it makes great sense to design the space out of an object, again by creating multiple parts that can be assembled later.

Finally, the same rule applies if you want your finished object to be multi-coloured: break it down.

Here, you should identify upfront which parts will be coloured differently and design them as separate elements, so that they can be printed and decorated (with no fiddly and imperfect masking required) before they’re finally brought together as a beautiful finished object.

Designing for desktop

These principles apply equally to the world of desktop 3D printing, if users of such machines are serious about making their output more sophisticated.

By way of an example, let’s compare two similar plastic toys, one 3D printed and the other assembled from injection-moulded parts.

Representing desktop 3D printing, the famous Makerbot Owl has been used to showcase the company’s hardware for many years now. As a point of comparison, consider Patrick Ryland’s Bath Duck for Ambi Toys — it’s a classic, simple, injection-moulded bath toy.

The Makerbot Owl is simply an owl shape, produced in a single colour. It does nothing. The shape itself may be nicely modelled, but as an object produced as a single 3D print, it’s a pretty crude one and ultimately rather uninspiring as a toy.

The Bath Duck, by contrast, is a very simple yet refined object, made up of just three colours — but it floats and its beak opens and closes. Children are mesmerised by it and it retails at just £5.99.

A bit of design thinking

The point here is that the kind of design thinking that has been applied to the Bath Duck could just as successfully be applied to the Makerbot Owl in order to make it a much richer object.

For a start, the log on which the owl stands could be separated in CAD and have some holes introduced to accept the talons of the owl. The log could then be printed in its own filament colour.

Then, the owl’s talons could be separately designed in order to attach to both the log and to the main body of the owl and printed in another, differently coloured filament.

The wings, too, could perhaps be separated and designed to fit back into the body once they too had been printed in a different colour. The same process could be applied to the owl’s eyes, its ear tufts, its breast feathers — you get the idea.

And in order to animate the beak, you would need to design both upper and lower parts.

The upper part of the beak would be designed to fix directly into the owl’s head, and the lower part designed to have a small internal pivot axle. The head could then be split in half and internal receiving lugs designed in position to receive the lower beak pivot.

The two halves of the owl’s head, meanwhile, would be designed to fit back together once they’d been printed in the same colour and then the whole head/beak combo could be assembled with an animated beak.

More effort, better results

Without question, it takes a good deal more time and effort to follow this approach — but it could be well worth the extra push, in terms of the sophistication and joy delivered by the finished object.

In fact, the process might not be as quite as laborious as I’ve made it sound here, since the longer the print job, the more vulnerable it is to build failure. In other words, numerous, smaller parts might make for a less error-prone build.

In fact, you might find that you’re able to produce these multiple, smaller components almost as quickly as you could produce a single, far less inspiring object.

Of course, it goes without saying that you’ll need additional CAD and design skills — but what better motivation could there be to develop your skills in these areas further?

The example I’ve given here is in no way proposed as an alternative to the production manufacture of injection-moulded bath toys.

It’s simply intended to illustrate how the application of design thinking can take objects made on a desktop 3D printer beyond the realm of simply shape-making, enabling you to deliver more elegant objects — ones that transcend the technology environment in which they were produced.

As desktop 3D printer usage takes off, and its user base extends from design companies producing quick visual prototypes at one end of the spectrum, to members of the public producing objects for their own purposes at the other, it seems to me that this design thinking approach is one that could make for better results right across the board.

Jonathan Rowley is design director at Digits2Widgets, a Camden, London-based 3D printing studio. A qualified architect, Rowley endeavours to help clients get the very best from the 3D printing technologies available today.

Break your ideas down to get better results from desktop 3D printers, recommends Jonathan Rowley

Default