Software-as-a-service is nothing new, but renting your tools can throw up some interesting challenges. Al Dean wonders where this trend is taking us and how we might tackle those challenges in future

Subscriptions to software: it’s one of those difficult subjects. And that’s because, as in so many other areas of modern life, there are such stark contrasts in opinion, so little nuance. You’re either for it or against it. No middle ground.

At DEVELOP3D, all of our software is provided as a subscription service, typically through monthly fees or annual payments, depending on the type of license and number of seats needed.

We have subscriptions to Microsoft 365, Adobe Creative Cloud, Dropbox, Pipedrive, Apollo for CRM and sales prospecting, plus a few other services dotted around for transcriptions from voice recording (Otter), video hosting and whatnot.

All of these services help our small company run. We make use of most of them daily and rarely come up against any issues – other than annual price hikes or changes in the packaging/bundling of services. We’ve planned ahead and, if we’re honest, have been lucky thus far.

That said, what happens when a software-as- a-service (SaaS) provider moves the goalposts? This throws up some interesting challenges, especially with large enterprise licenses and for those managing corporate software budgets.

Yes, price hikes are something that we’re all accustomed to and even see as inevitable. Just because something cost £25 a month six years ago, doesn’t mean it’s going to stay that price forever.

But then there’s the moving of functional goalposts. An example where this might be considered a good thing is seen with Autodesk’s Fusion 360. Once upon a time, it had two tiers. Then that was reduced to one tier only, which brought a whole set of functionality (such as some pretty damn advanced CAM functionality) into the standard price subscription.

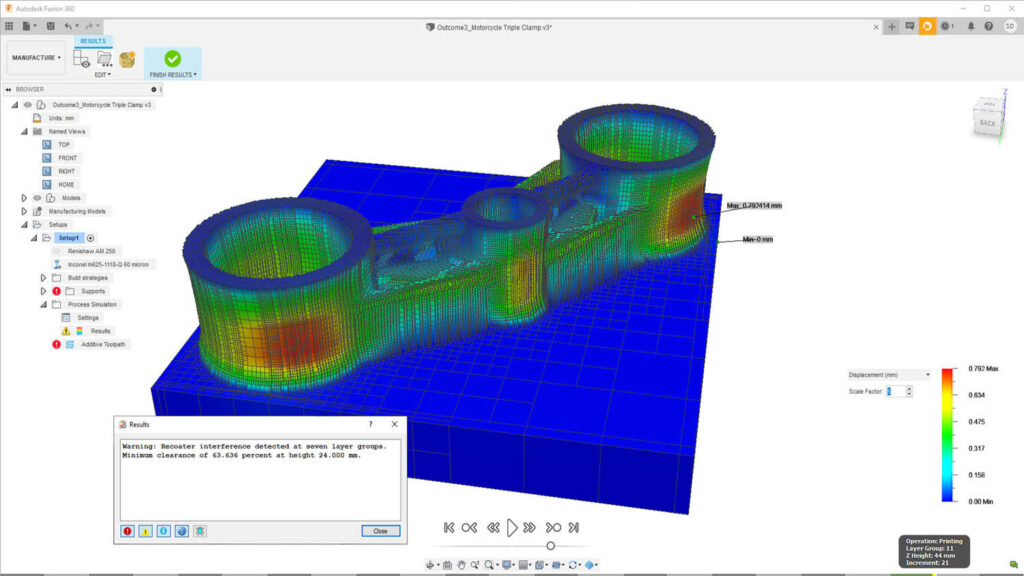

Autodesk has subsequently added a new approach, offering ‘extensions’ that provide specific capabilities for advanced machining, additive preparation, simulation and more. In other words, it’s an upper tier. An upper tier by different name and means, but an upper tier nonetheless.

At the same time, it makes sense. The number of folks who need on-machine inspection in their CAM system is limited, as are the number needing simulation tools for powder-bed fusion additive manufacturing.

Then there’s the removal of capabilities, combined with the introduction of subscriptions. This is something that really ticks me off.

A recent example is Cricut, supplier of some pretty nifty desktop CNC cutting machines. In March, the company announced that it is introducing a subscription fee for its cloud-based Design Space application. Essentially, if you want to cut anything on a Cricut machine, you need to upload to this app, carry out preprocessing and sheet layout, and then send it to the machine to cut. What the company was intent on doing was limiting users to 20 uploads per month. That, to my mind, is insane.

One week you might purchase a piece of hardware; then the following week see restrictions placed on how much you can use it. Irrespective of the vendor’s justifications, it’s plain wrong.

Of course, existing customers were outraged, quite rightly. And Cricut soon backed down, posting an open letter from CEO Ashish Arora that stressed the company’s core value of community.

The Cricut team had listened to the feedback and taken it on board. (And no surprise there, given that much of that feedback indicated that customers were inclined to abandon their Cricut machines and shop with competitors instead. That sort of talk pretty much always makes a CEO sit up and take notice.)

Ultimately, software-as-a-service subscription-based licencing isn’t new, but it is becoming more prevalent. For the customer, there are benefits and there are drawbacks. There is no right or wrong. What really matters is value. And value is inextricably linked to affordability, as well as defining a potential escape route.

Does the system provide the value you seek, in terms of support or the functionality provided? Does that functionality increase in robustness, quality and capability over time, to your benefit as a user?

We also need to consider that the intellectual property (IP) embodied by, say, a Photoshop file, an InDesign document or a cut vinyl shape may not be of particularly high value. It might very quickly be moved to an alternative platform.

But when it comes to 3D design tools, that’s simply not the case. There is huge value tied up in the data we create, both the hours spent on it, but more importantly, from an IP standpoint.

The rise of subscription-based design and engineering systems doesn’t really change much in the use case or how it’s financed. But what it does change is the need to formulate an robust exit strategy – and once that data is out there in the cloud, what then? That is where the real shift lies, and that’s where our real focus – even concern – should be as customers.