Technology in the healthcare sector is changing. There’s a move towards mass customisation and this means bespoke medical parts for a huge range of applications including prosthetics, dentistry, and podiatry.

In some cases, this is being made possible by bringing design and manufacturing technology directly into the hands of laboratories and medical professionals. CAD/CAM specialist Delcam is fuelling this trend.

Having built its reputation on solutions at the ‘meaty’ end of the design and manufacturing process, the company has recently set up a dedicated Healthcare Division that has been formed specifically to deliver tailored CAD/CAM solutions to the healthcare industry. DEVELOP3D’s {encode=”al@x3dmedia.com” title=”Al Dean”} caught up with Chris Lawrie, the man responsible for marketing the new division, to discuss why Delcam thinks it can take on the medical market and what challenges lie ahead.

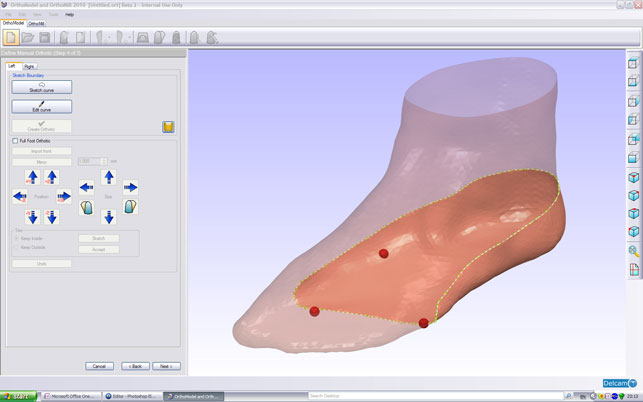

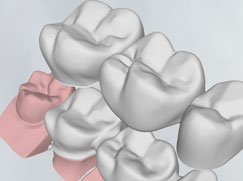

Modelling an orthotic around a scan of a foot inside Delcam Orthomodel

AL DEAN: Delcam has a reputation for dealing with the ‘business end’ of the design to manufacturing process, so how did the Healthcare division come about and why you think you’ve got the technology to solve a very different set of problems?

Chris Lawrie: The common denominator is complex freeform shapes – nothing is more complex and freeform than the organic human form – and we’ve always handled this well. There’s also the difference between mass customisation and mass production. In the medical sector, there are both, but as 3D scanners become cheaper and more accurate, the more the balance will change towards mass customisation.

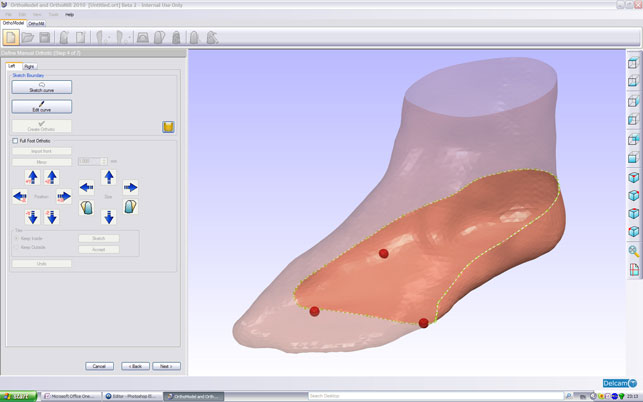

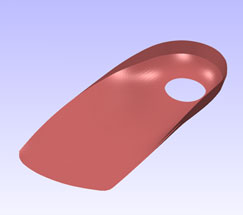

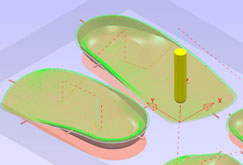

Orthotic insole designed with Delcam Orthomodel

Take a high precision dental scanner, where they want 10 microns of accuracy for fit. 15 years ago, these would have cost £80,000 upwards. Now they’re selling for £8,000 – because there’s now much greater volume. When combined with more readily available rapid prototyping and high-speed machining, we now have this point of convergence.

For example, I can capture your face in an instant with a scanner that’s £20,000. It’s highly accurate, it’s full colour and I can manufacture a facial prosthetic that’s accurate to within half a millimetre. This can be done for a foot, for a body brace, for a leg brace, for cranioplasty caps for skull deformities or dental work. It’s the combination of technologies that is the enabler.

AL DEAN: How do you take this range of technologies and turn them into products specifically for the medical market?

Chris Lawrie: Delcam are exploiting this opportunity by getting the dental and orthotics [to support musculoskeletal abnormalities] solutions done and we’ll soon have a maxillofacial [treatment of the hard and soft areas of the head, face, jaw, neck] software coming onto the market. All of these essentially do the same thing: Scan, rapid modelling and rapid manufacturing at the end – either with high-speed machining, high-speed routing, or rapid prototyping/manufacturing.

Modelling a bridge inside Delcam DentCAD 2010

We’ve developed three specialised Digital Laboratories. The Dental Digital Lab assists with the design and manufacture of dental restorations. OrthoModel and OrthoMill support the design and manufacture of orthotic insoles. Orthotics is the design and manufacture of devices that support or correct musculoskeletal deformities and abnormalities. This is a rapidly growing field, both for medical purposes (to assist with the natural imbalance of the human body and for diabetics). It’s also gaining interest in the consumer market, with the lead being taken by the sports industry.

FaceMaker assists with the design of maxillofacial implants. Maxillofacial refers to the treatment of the hard and soft areas of the head, face, jaw, neck. We’ll be expanding our solution set as we move forward.

AL DEAN: How does the concept of Digital Laboratories differ from a collection of technologies that a medical professional puts together themselves?

Chris Lawrie: The scanning and manufacturing technologies are available now and affordable but the problem has been that in the middle is a huge piece of software that the professional has to learn in its entirety, only to carry out three, four or five steps to get to an end result. One size fits all doesn’t work in medical. What we’ve done is to take the complexity out of the process and create very streamlined tools.

In the case of OrthoModel, it’s 20 buttons. When we showed it to the prosthetists for the first time, instead of them saying, “Is that all?” What they said was “Thank god we don’t have to go and learn a complete product. What you’ve given us is the tools, designed in consultation with professionals, to do the job.”

DentMill is a 3, 4 and 5 axis Dental CAM program for all types of dental manufacturing

AL DEAN: Are you targeting the laboratories with these solutions or are you looking to move them into the hands of the medical practitioner?

Chris Lawrie: What you typically find is that the practitioners outsource manufacture to a laboratory to make the parts. As a result, we’re focussed on selling these solutions to the laboratories to begin with. That said, in the future, we’ve got to make it even simpler because we want the practitioners; the prosthetist, the orthotist, the podiatrist, the dentist; to do the work. As a result, we’ve got to make it even simpler but equally keep it just as powerful beneath the hood.

The next wave of activity for us is to create cost-effective solutions to enable the practitioner to hit the laboratory with detailed design content, rather than just a vague request. Once again, the cost of the scanner technology is key. For the podiatrist to want to own it, it’s got to be a thousand pounds of capital outlay at the most.

So we’ve now got to get creative and provide solutions that are very cheap to invest in, in volume. Say we’ve currently got a thousand laboratories in the world for orthotics. There are probably half a million practitioners – that’s a huge shift in how price and acceptable complexity affect the solutions.

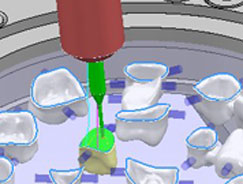

OrthoMill can output machining instructions to any milling machine

The key point about the solutions we’ve created is that we’ve got 40 years of CAD/CAM experience which can be run as engines and overlaid with a slimmer user interface. The user interfaces we’ve created for dental, for orthotics and for FaceMaker are all designed by professional practitioners, not by us – that’s absolutely essential. Rather than going out there and saying “This is how you will work,” we’ve built a solution that works in the practitioners’ and professionals’ language and uses the same workflow that they use day to day. Because we’re putting them into a paradigm shift, from a very manual process into a digital one, we have to use their language and maintain their existing expertise in the process.

AL DEAN: How challenging is it to adapt your digital solutions to match traditional and well established manual processes?

Chris Lawrie: It’s a huge challenge but it’s easily solved – by listening. We’ve formed a healthcare advisory board so we’ve now got healthcare professionals who are investing in Delcam at their own cost (in terms of time and effort). The people we have on board have a personal interest in Delcam getting it right, so they’re quite happy to give their time when we meet once a quarter to discuss a specific subject. When we’re looking at building a solution for creating diabetic soles for the insole market, we’re much better off talking to diabetic care specialists. It’s a challenge to get it right, but because we’ve got the right approach, taking our CAD/CAM knowledge, then seeking out the medical knowledge to match with it.

Delcam claims no prior CAM experience is required to operate its dental machining system, DentMill

AL DEAN: How does developing products for the medical market differ from traditional design and engineering?

Chris Lawrie: An interesting comparison is that in engineering, everyone is fighting for the crumbs so they protect their intellectual property and that stifles movement and sharing of information. For example, when a company has invested in the development of one product or process, they don’t want that information and knowledge to be used by their competition – so they’re very protective and understandably so. We’re creating a set of tools that enable the medical technician to create a product using their own skills and understanding. We’re not stifling them with a prescriptive process; we’re giving them the flexibility to put their intellectual property, their knowledge and expertise, to best use. Each has their own take on how it’s done. What we shouldn’t do is limit them to the process used by someone around the corner.

The challenge is to make sure that we’re flexible but not so broad that the solution is huge. Basically, it’s keeping it simple without removing individual interpretation. Because many of these are manual and knowledge-based processes, there are definite views about how things should be done. It’s trying to balance the simplicity of the process while maintaining some sort of flexibility. A lot of that comes down to listening to potential customers and people that are willing to give their time to ensure they get a product they actually want.

AL DEAN: How regionalised is the medical market? The engineering world is a global enterprise these days but how does the medical sector stack up in terms of national or more regional activity – is there much of a difference in customer interaction and recommendation?

Chris Lawrie: Absolutely. There’s a much more open attitude. If I took two podiatrists and put them in room and got them to talk about feet, they would not agree on how to treat you or me. There’s a huge academic prowess within the medical field. But those same two people would readily recommend ideas and technology to each other and because of two reasons. Firstly, that openness and secondly, it’s a much more regional business. In the UK certainly but, in the US, it’s even more fragmented, where there’s no national or even state level healthcare program.

As long as we give the user the ability to adapt their manual processes within the software, they’re happy to recommend the software/solution as a generic tool to another lab that’s 500miles away because they have a different customer base. They’re not giving away their knowledge by recommending our software, because they use their knowledge and understanding to make a different device or product and protect their own IP. What we’ve ended up with is this huge peer-to-peer viral marketing thing going on between the laboratories.

Half of the sales we’ve made in the orthotics industry have come from recommendations from existing customers. Something you would rarely see in the mainstream engineering market. In engineering you get brand awareness eventually through a volume of sales. What we’ve done is introduce a product to one orthotic laboratory two years ago and by word of mouth and viral marketing, we’re now recognised as being in the top three systems in the world.

The other thing is that our Digital Laboratory creates capacity by reducing the time required to manufacture the products. It was a cottage industry, with a lengthy and expensive process to cast a foot. Going to the digital route with scanning and CAD/CAM has created an explosion of capacity so they can move orthotics volumes up into the mass market.

Retailers are starting to take an interest because what was a ridiculously lengthy process of casting a foot didn’t belong in a store, whereas if you can walk into a store, put your foot on a scanner and have a bespoke product made very quickly at the same cost as mass production, then you’ve got a retail market – whether that’s comfort insoles, sporting insoles or some stage in the future, store front dental restorations. Who would have believed 20 years ago, you could make spectacles in an hour? Technology is the enabler and we [the industry] are at the dawn of a new era.

www.delcam.com

Chris Lawrie welcomes a new era in medical design and manufacture