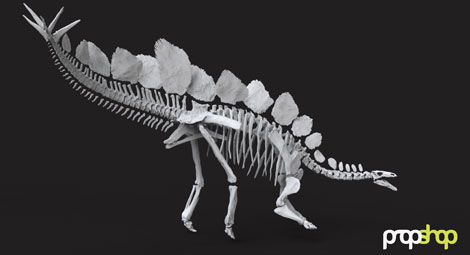

Sophie the Stegosaurus, working it for the cameras

The Stegosaurus – six metres and several tonnes of belching, farting lizard meat – last roamed the earth 155 million years ago, which is why we’re very happy to see one finally making it to London.

With a worldwide scarcity of well-preserved skeletons, London’s Natural History Museum, in a private donor assisted coup, somehow managed to purchase a Stegosaurus discovered in 2005, in Wyoming, USA.

Nicknamed Sophie, the skeleton is on display at the museum, but it also gives museum staff a chance to do more research into the big girl – starting with getting the entire thing laser scanned.

Its 5.6 by 2.9 metre frame was 3D scanned by Propshop, creating a 3D digital template of the entire skeleton that allows the Natural History Museum’s team to run some key-question simulations about how Sophie managed to live all those years ago.

Propshop also 3D printed specific pieces of the skeleton from the scan data, producing parts that could be handled close-up by researchers and safeguarding against possible future loss or damage of the original.

“Stegosaurus fossil finds are rare,” says Professor Paul Barrett, the museum’s lead dinosaur researcher (probably unaware that my 7-year-old self is deeply envious of his job).

“Having the world’s most complete example here for research means we can begin to uncover the secrets behind the evolution and behaviour of this intriguing dinosaur species.”

The skeleton was scanned using Lidar technology, and the data gathered from the noncontact handheld high-res laser scanner, then digitally manipulated to create a highly accurate 3D CAD model.

“We 3D printed the skull, the radial plates and tail bones using one of voxeljet’s larger printers, the VX1000, and then fabricated and finished the parts using traditional modelling craftsmanship.” explains James Enright, Propshop’s managing director of Voxeljet UK.

As well as being unsure as to the function of the Stegosaurus’s plates, or knowing exactly how it moved, palaeontologists have long been flummoxed as to how a dinosaur weighing in the region of 2,000Kg and possessing, says Professor Barrett, such ‘feeble looking teeth’ could have managed to sustain itself.

Using Propshop’s digital and real-world models, the museum will be able assess the strength and bone density of different parts of the skeleton, work out how they both fitted together and moved in relation to various functions – chewing, for example – and so begin to gain a much better idea of the Stegosaurus’s diet, it’s size, and whether indeed its plates were less a means of defence and more a giant self-cooling system.