7 inspiring historical female engineers to celebrate on National Women in Engineering Day

In celebration of it being National Women in Engineering Day we’ve come up with a list of 7 different female engineers that you should probably raise a drink to today.

Beginning in ancient Greece, our list thereon is predominantly British female engineers that vary their skills from Indian railroads to manufacturing methods, eclectic designs to computer programming hundreds of years before the computer was even invented.

Here are 7 for you to remember:

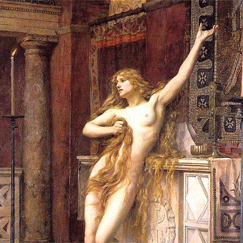

Hypatia – the Greek mother of mathematics

1 – Hypatia (370 – 415 AD)

The only non-Brit on our list, engineers don’t get much more dramatic than the Greek mother of mathematics and female founder of engineering, Hypatia; an Alexandrian Neoplatonist philosopher in Egypt, she was murdered by a mob of Christians.

Sadly her works were badly documented (most of which are partly attributed to her father, also a prominent mathematician), although she became head of the Platonist school at Alexandria in about 400 AD, lecturing on mathematics and philosophy.

Ada Lovelace – anticipated the development of computer software and calculations hundreds of years before a computer was built

2 – Ada Lovelace (10 December 1815 – 27 November 1852)

Often listed as the world’s first computer programer, Lovelace took an interest in mathematics and the analytical engine pioneered by Charles Babbage, well before the hardware was ever possible.

Lovelace wrote a scientific paper in 1843 that anticipated the development of computer software, artificial intelligence and computer music thinking/calculating machine. These notes contain what is considered the first computer program – an algorithm encoded for processing by a machine.

Verena Holmes – the first woman member elected to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers

3 – Verena Holmes (23 June 1889 – 20 February 1964)

A mechanical engineer and inventor, Holmes was the first woman member elected to the Institution of Mechanical Engineers (1924), and a founding member of the Women’s Engineering Society.

Holmes designed apparatus for treating patients with tuberculosis, a surgeon’s headlamp, a poppet valve for steam locomotives, and rotary valves for internal combustion engines, holding patents for 12 inventions for medical devices and engine components.

The Women’s Engineering Society continues to support the yearly Verena Holmes lecture, given at various venues across Britain to children aged 9 to 11 to encourage interest in engineering.

Sarah Guppy – patented the method of safe pilling of bridge foundations, used by Brunel, amongst others

4 – Sarah Guppy (1770 – 1852)

With more exciting ideas than you could shake a stick at, Guppy’s various designs varied from methods for preventing barnacles forming on boat hulls, to an all in one breakfast-making solution (makes a cup of tea, boils an egg and keeps your toast warm).

Her patented method for the safe pilling of foundations for bridges in 1811 was used by Thomas Telford when building his bridge over the Menai straits, and by Isambard Kingdom Brunel with the Clifton Suspension bridge. Guppy never charged for the use of these methods as she regarded the projects as being for the public benefit – adding a philanthropic bonus point to her name.

Alice Treadwell – helped manage the building of the mammoth Great India Peninsula Railway

5 – Alice Treadwell (1823 – ????)

When her husband Solomon popped his clogs a mere 15 days after landing onsite at his latest engineering project in India in 1859, Alice Treadwell decided to take over proceedings – building the mammoth Great India Peninsula Railway.

Across an area so tricky to build on, substantial engineering works were required including 2.25 miles of tunnelling and eight masonry viaducts. Treadwell appointed new engineers and oversaw construction through to the railway’s completion in 1863.

Eleanor Coade – oversaw the manufacturing of Lithodpyra stone, the building material of choice for Victorian London

6 – Eleanor Coade (3 June 1733 – 16 November 1821)

A manufacturing marvel, Coade’s factory was responsible for producing ‘artificial stone’ Lithodipyra (stone fired twice), a moulded, weather-resistant, ceramic stoneware that could produce multiple copies of a design.

Coade cultivated strong business relationships with respected architects and designers, seeing it used in prominent London statues and decorative features, resisting the corrosion of the City’s notoriously polluted air, made damaging by coal exhausts, formation of acid rain, and other industrial-age nastiness.

Sarah Losh – a rare commissioned architect and champion of local craftsmanship

7 – Sarah Losh (1785 – 29 March 1853)

At a time when Cumbria was packed with men dandying around, spouting romantic poetry about clouds and daffodils, Sarah Losh was hitting the books to learn about design and architecture.

As a result of becoming heir to her father’s estate Losh was well read and well educated, attending schools in Wreay, London, and Bath, and travelling to France, Italy, and Germany.

As well as maintaining the family industry, the results of her architectural learnings are to be seen in her home town of Wreay, which is scattered with buildings that she designed, influenced by her travels.