Kalkhoff’s efforts to accelerate physical prototyping for its bicycle frame looked to have hit a rut, until Materialise got them back on track. Stephen Holmes reports on how the company 3D printed an aluminium prototype in record time

With over 100 years of experience, Kalkhoff knows how to build a bike that goes the distance. But even the German manufacturer is impressed with the speed at which its latest e-bike moved from concept to physical prototype testing.

It can take years to ready a bike for production, with product development for any new Kalkhoff product always a balancing act. Designers need to maintain the unique geometry now synonymous with the visual identity of Kalkhoff e-bikes, while also considering functional ability and the necessary components for the design.

The company strives for its bikes to be comfortable, agile and reliable, giving every customer a smooth and enjoyable riding experience. To achieve this, the company tests each bike’s frame well beyond the industry standard.

Usually, a bike frame must pass loads of up to 150 kg. In comparison, Kalkhoff’s frames are pushed to tolerate loads of around 170 kg. “Our business prides itself on providing our customers with the opportunity to cycle freely without limitations,” says Kalkhoff industrial designer Rik Maes. “Cycling should reflect our company motto: ‘Kalkhoff moves you everywhere,’” he says.

For prototyping to begin, rideable models must be first produced – an expensive and time-consuming process that requires tooling to be cut, and which cannot be undertaken with plastic form models.

With this obstacle in mind, Kalkhoff contacted its polymer additive manufacturing supplier Materialise, to discuss a potential solution through metals 3D printing.

Metal heads

With Materialise’s Metal Competence Center (MCC) for 3D printing located in Bremen, close to Kalkhoff’s headquarters in Cloppenburg, the teams met to begin optimising the bike’s design for additive manufacturing in aluminium.

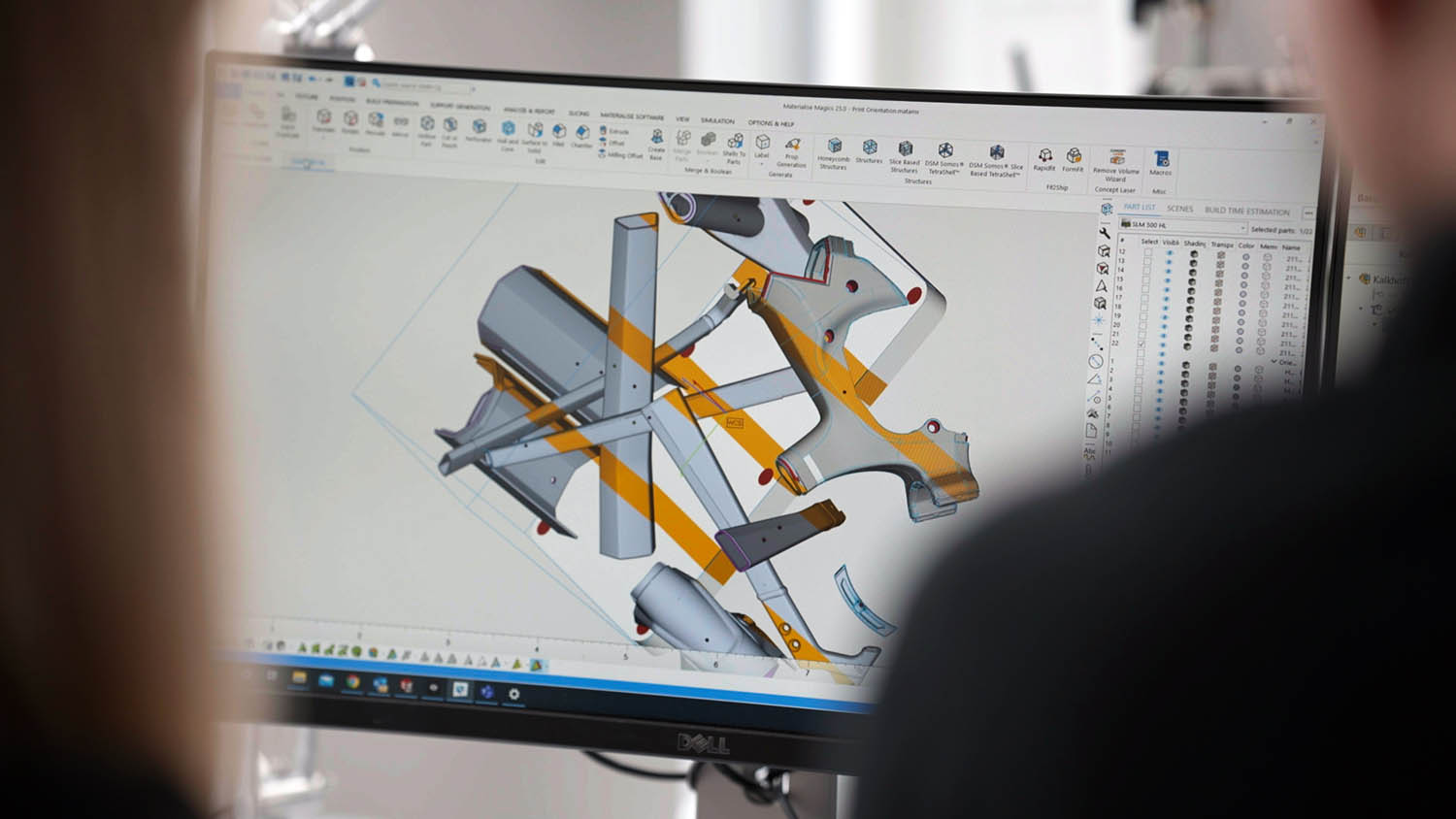

With the maximum part size for Materialise’s SLS 3D printers set at 500 x 280 x 315mm, building the full frame as a single piece was not an option, so the first step was to convert the 3D CAD model of the bike into printable sections.

The optimal segmentation of the design was determined in Materialise Magics, positioning the cuts on the frame to consider existing loads to avoid peak stress in the welded joints and ensuring that an entire bicycle frame would fit into the 3D printer’s build chamber.

Optimising the build strategy also helped to reduce machine time and post processing efforts. Once the joining segments were defined, the end segments were redesigned in CAD to create a better welded surface once printed.

Welding and testing was performed by Seefried, a company specialising in small series welding and located near the MCC. ACTech, a Materialise-owned specialist in metallurgy and low volume production took care of heattreating the welded frame, performing this task via two processes — solution annealing and artificial ageing.

While components were being printed, the simulation for the welding and heat treatment of the frame was run simultaneously using the 3D CAD data, helping streamline the process even further.

“Situations like this and moments such as after the annealing stage that require real-time measurements of the frame with millimetre-accurate geometry are not possible without close cooperation and the expertise of all those involved,” explains Michael Röhner, product manager metal 3D Printing at ACTech.

Expectations surpassed

Typically, the complete development of a bike takes between two and two-and-a-half years. By using metal 3D printing and the expert know-how at Materialise, the whole prototype frame was delivered in six weeks from start to finish — an overall saving of three months in the development phase.

“Metal 3D printing has surpassed our expectations,” states Maes. “We can make changes at short notice, because no tools or moulds were specifically needed to be built for this model. In the development phase or the ‘engineering design freeze,’ we will have mobile design prototypes where we can test all the selected parts. This has never been possible!”

Additionally, producing the frames with local partners meant Kalkhoff could save time, get the test results faster and feed any changes back into the design without worrying about long transportation waits from Asian suppliers.

“That’s a good thing for us, as we’re first to market with innovative bikes for our customers!” concludes Maes.

Once testing is complete, the test bikes go on to fulfil other purposes. For example, new designs are available for showcasing at marketing events and for test rides long before the production models reach the market. The process also acts as an exploratory step towards more sustainable future production methods that will help shape the next century of Kalkhoff’s designs.