General Fusion is aiming to deliver commercial fusion energy generation within the next decade and multiphysics simulation is proving key in the race to unlock fast and safe iterations of its reactor design

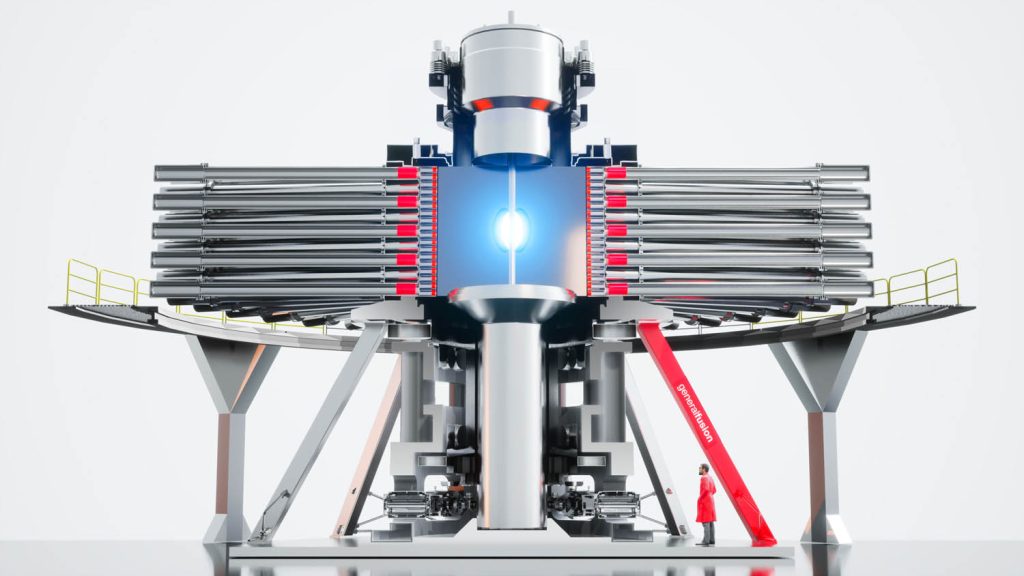

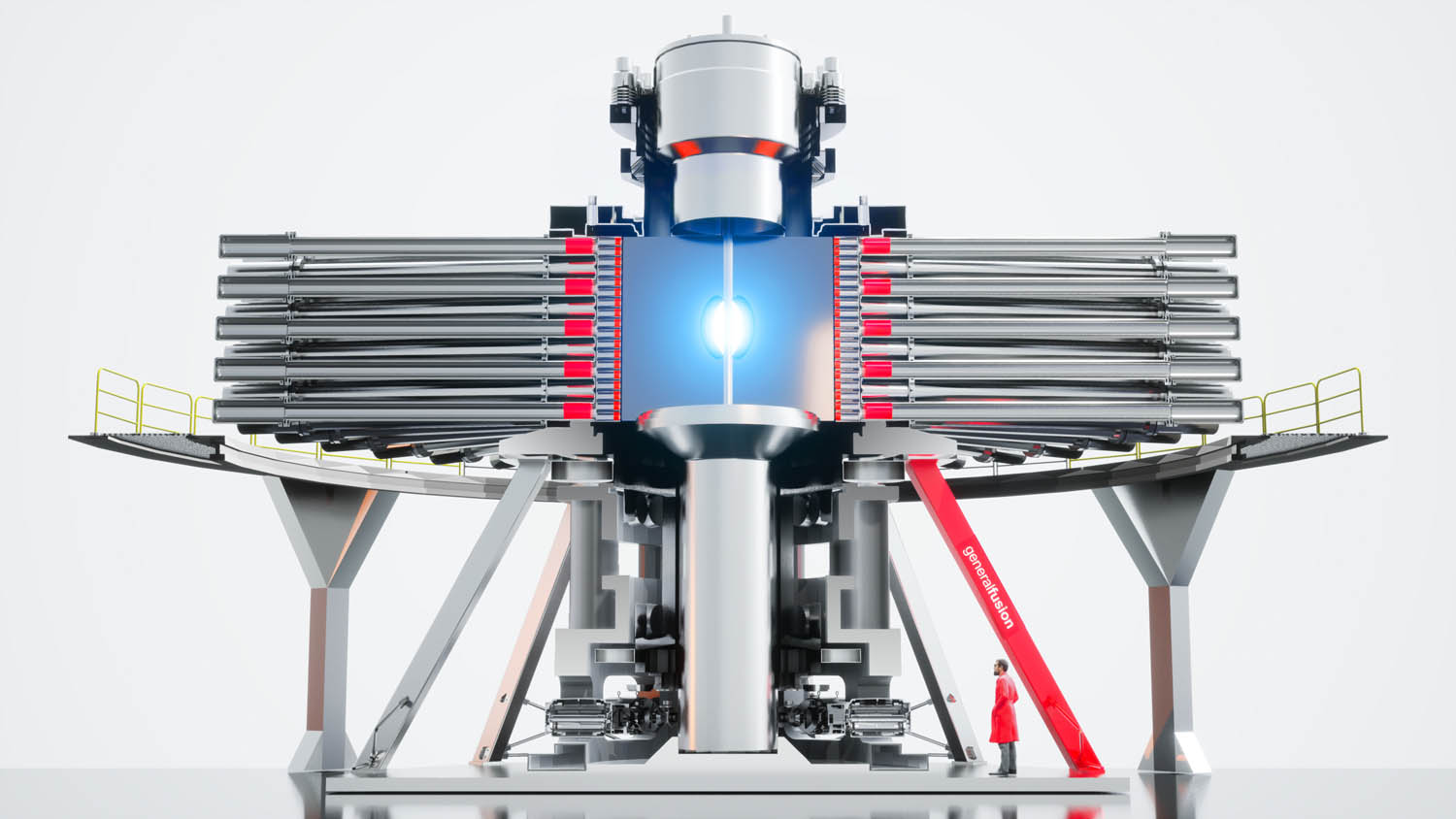

On its journey to deliver a fusion reactor capable of powering commercial energy grids, General Fusion’s Lawson Machine 26 (LM26) represents an important milestone. LM26 has been developed to de-risk the company’s planned introduction of a machine based on its Magnetized Target Fusion (MTF) technology. This works by compressing a magnetised plasma with a liquid metal liner to achieve the high temperatures and pressures needed for fusion. General Fusion, founded in 2002 by physicist Dr. Michel Laberge, plans to commercialise this technology by the early- to mid-2030s.

The promise is certainly intriguing. MTF power plants have the potential to produce significant amounts of energy using comparatively inexpensive technology and without creating carbon emissions.

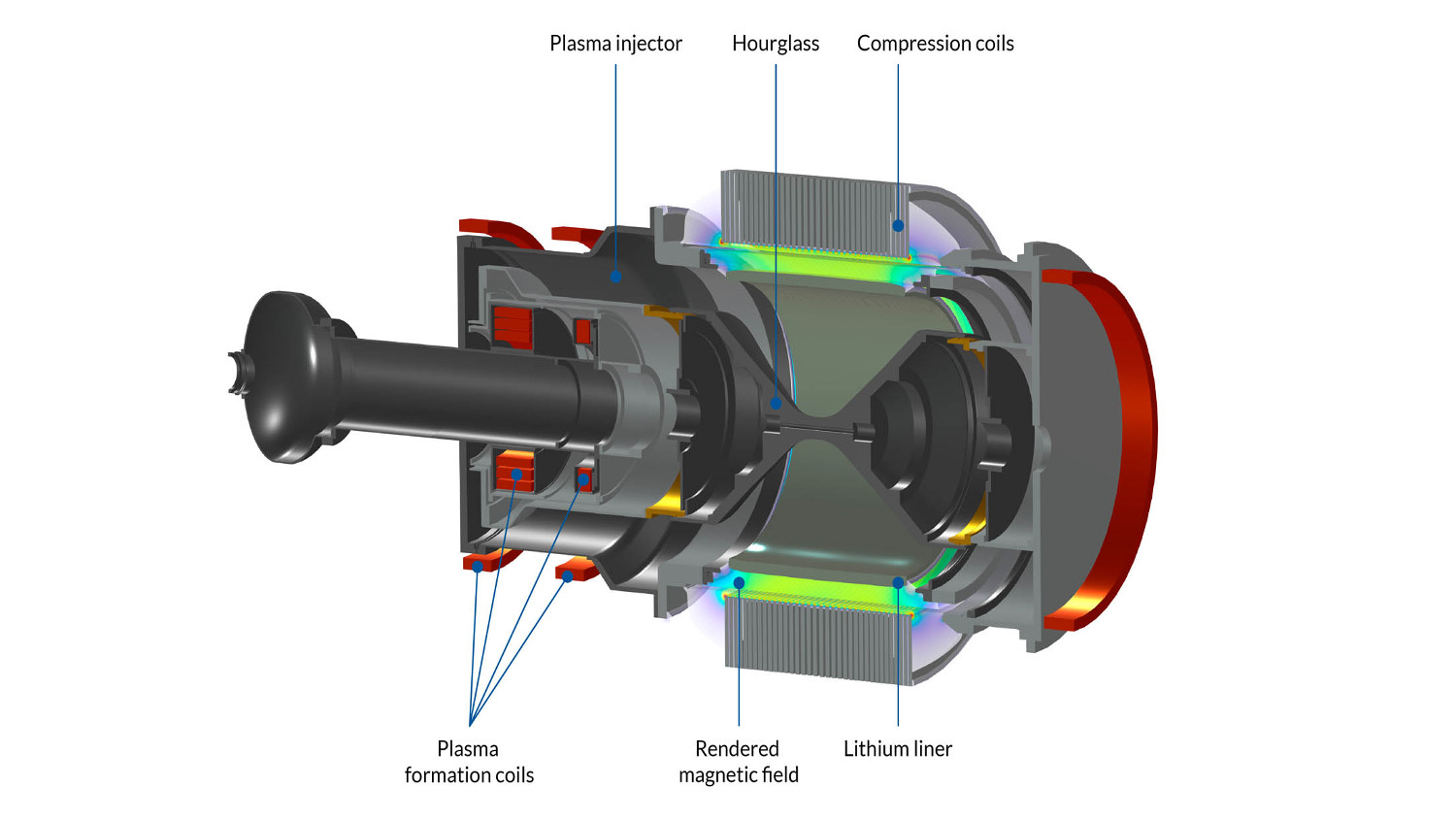

In a General Fusion MTF machine, hydrogen plasma is injected into a liquid metal vessel formed inside the fusion machine. From there, an array of pistons compress and reshape the liquid metal vessel around the plasma, increasing the density and temperature of the plasma, leading to fusion.

It is a pulsed approach that repeats once per second in a commercial plant, with the liquid metal wall of the vessel capturing the energy of the neutrons, converting it to heat, which when passed to a heat exchanger creates steam and ultimately produces electricity.

The use of pistons is unique to General Fusion’s approach, as other fusion methods rely on superconducting coils, lasers or other expensive equipment.

“For MTF, the larger the initial plasma volume, the more time it can stay hot, which gives us more time to compress the plasma to fusion conditions,” says Jean- Sebastien Dick, an engineering analysis manager at General Fusion.

“At General Fusion, we have been iterating on the process and developing a power plant operating point that is not only commercially viable but also very competitive against other types of energies on the market.”

LM26 is targeting the key temperature thresholds of 1 keV, 10 keV, and the equivalent of scientific breakeven by compression of a solid lithium liner.

Performance predictions

When it comes to modelling and measuring internal effects in order to predict the performance of the LM26 design, General Fusion turned to Veryst Engineering, an consultancy firm that specialises in highly non-linear simulation and material modelling.

One of these experimental tensile tests included measuring the material response of solid lithium. Using a high-speed camera and impact load cells, Veryst and General Fusion heated lithium with a pair of ceramic heaters and pulled the sample to failure in order to measure the stress-versus-strain response. The results were then used to calibrate a Johnson-Cook model.

“The full model is quite complex,” says Veryst principal engineer, Sean Teller. “It utilises a moving mesh for the lithium and the compressed plasma, as well as nonlinear solid mechanics and the Johnson-Cook material model, and EM forces from modelled circuits drive the compression of the lithium. The lithium liner impacts the hourglass device, so capturing the non-linear contact is crucial to perform accurate predictions.”

To add to the complexity of this task, heat transfer occurs between all of these model components.

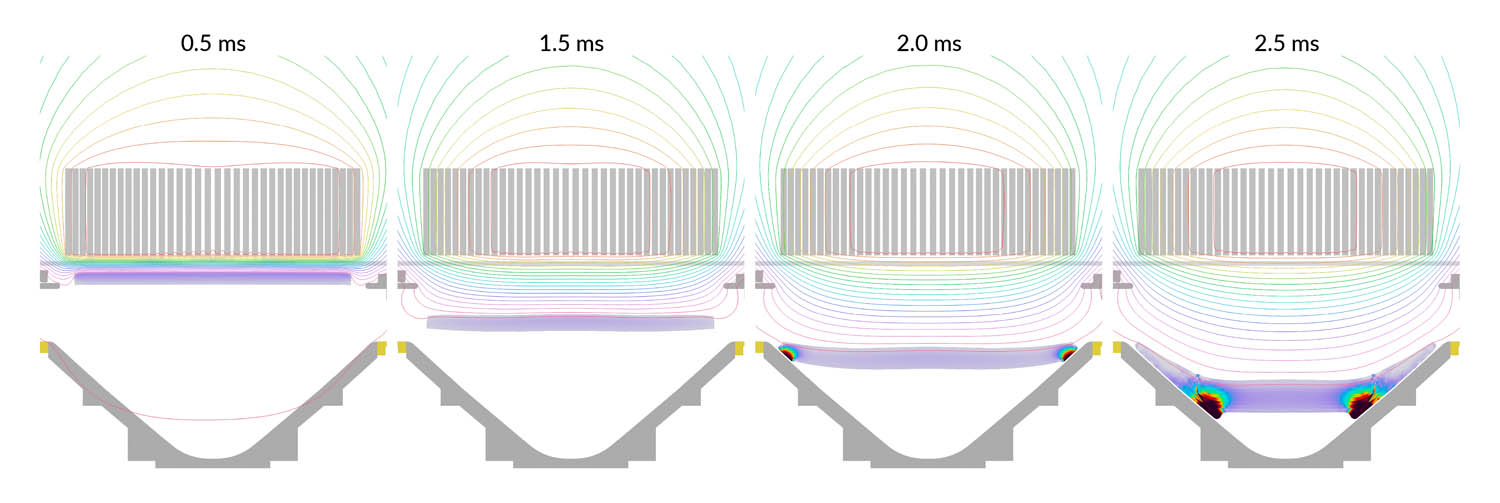

As Teller explains, Veryst used Comsol Multiphysics simulation to enable the team at General Fusion to quickly iterate on its designs for LM26. Various different LM26 designs could be weighed simultaneously and in the same space in the Comsol software. Veryst and General Fusion used a time-dependent, fully coupled solver and automatic remeshing to capture the large deformation and pressures inside LM26.

“All of this required tight integration between the physical tests and the finite element models to gain fundamental insights into this compressor design,” says Teller.

During the validation campaign of models in the development of LM26, General Fusion compressed 40 lithium liners using electromagnetic compression to validate the Comsol model. The team conducted physical experiments using a small-scale prototype of the compression system.

To measure the deformation of the liners, General Fusion developed a structured light reconstruction (SLR) technique. This involves the use of sheets of laser light to extract the velocity at multiple points in the liner.

General Fusion also used photon Doppler velocimetry to measure the velocity of the centre point of the lithium liner. This combination enabled the team to recreate the deformation observed in physical experiments and compare it to simulation results for validation. They then used that rate- and temperature-dependent material model in subsequent simulations of the plasma compressor and found good agreement between the test data and the data acquired through previous tests.

“The performance of the compressor would not have been possible without the insights gained from the early simulations and the multiphysics model, in particular, that helped drive this design,” admits Teller. “These validations increase confi dence in future modelling eff orts to further drive the devices to achieve the Lawson criterion and clean power.”

Rapid compression

One of the key components of LM26 is its electromagnetic compressor, which is responsible for the rapid compression of the magnetised plasma. The design for this element must be able to match its impedance with the compression time of the machine to best convert a signifi cant fraction of the initial stored electrical energy into kinetic energy.

Modelling and simulation enabled General Fusion to adjust the impedance of the power supply, see how design alterations impacted performance, and maximise compression efficiency.

To tune the impedance, Dick used the Comsol software to make adjustments to the number of turns in the compressor’s coils, altered the initial distance between the liner and the coils (known as the ‘air gap’), and altered how the liner was compressed over its trajectory.

Additionally, the liner shape along the compression needs to be controlled to ensure that the plasma stays stable, requiring iteration to the liner thickness and the axial spacing between the coils.

Dick solved the model after making different design adjustments and compared the results to see if the machine could achieve a stable plasma compression.

“We have done multiple material characterisation campaigns to make sure that this liner behaves as expected under the high strain rates and the high plastic strains we are experiencing in these compressors,” says Dick.

Comsol’s framework allowed the engineers to incrementally build in complexity and gain confi dence in design intentions without having to reiterate the design phases, explains Dick. “We have not had to change any major parts of these experiments. They were always behaving as intended,” he says.

Using the Cluster Sweep node in Comsol Multiphysics, General Fusion was able to run its simulations in a much shorter time frame than expected, with the tool allowing it to create one large cluster job that spans several nodes. The more nodes that have been added directly relates to the amount of parameter values that are computed in parallel. General Fusion used this to tackle multiple parameters in a quicker fashion.

“In the past, running these simulations would have taken multiple weeks or even months, but now we are doing this in less than 24 hours,” says Dick. “We are able to get hundreds of simulations done in that time span on our cluster.”

Multiphysics simulation and fusion research will continue to be inextricably linked as General Fusion pushes this new source of power to greater levels.

LM26 achieved ‘first plasma’ in February 2025, successfully compressing a large-scale magnetised plasma with lithium soon after in April, before financial constraints hit and the company was forced to go in search of funding. But its leadership remains positive and committed to the company’s distinct pathway, founded on entrepreneurship and a keen commercial focus, which it believes will lead to a clean-energy breakthrough.

The sooner that comes, the better – and multiphysics simulation is vital to quickly testing iterative designs built to light up the grid in just a few years’ time.