Swatchbook Mix – Analogue material specification processes can’t keep pace with the speed at which today’s industrial design and product development specialists work. We look at a system designed to take these processes fully digital

On a mission to revolutionise the exploration, visualisation and sharing of materials, Swatchbook was set up in Irvine, California back in 2017.

It’s the brainchild of former executives from Luxion (KeyShot) and Foundry (Modo) and, while we talked to that team around the time of the company’s launch, a more recent chat has shown us just how far Swatchbook has come since then.

So now seems like a good time to provide a solid update on its capabilities. At its core, Swatchbook’s rapidly expanding product offering focuses on the management and visualisation of materials – for now, primarily in the areas of apparel, footwear and home goods. But the platform is built to host any type of material and asset.

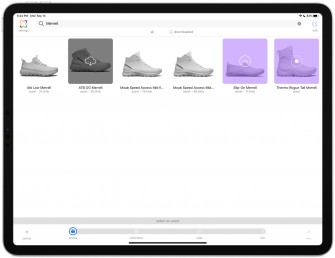

Its services, meanwhile, aim to provide a way for designers to explore materials in a variety of ways, browsing either their own inter libraries or the growing library of materials provided by Swatchbook’s partners. Those partners are typically vendors of fabrics, technical materials and associated items such as fasteners.

Whether they’re exploring their own materials or those from suppliers, Swatchbook’s library provides the user with an intuitive way to explore, group, collect and manage materials captured in a highly realistic way.

This is a process that’s traditionally analogue in nature, based on collecting physical samples (swatches), managing spec sheets and datasheets and using a number of basic digital tools. Swatchbook, by contrast, is looking to move that process into the digital realm, with significant advantages for everyone involved.

Consider, for example, the sharing of material swatches: a physical swatch would need to be selected and shipped, which has time and cost implications.

Using Swatchbook, the swatch is scanned once and then made available to whoever needs it. It can be visualised using photorealistic rendering, both within Swatchbook’s own services (which we’ll explore shortly) or downloaded for use in your own visualisation applications.

The supplier of the material, meanwhile, is connected to the designer/potential customer, and the designer benefits from having a managed set of data about that material, immediate access to the supplier and assets ready for use downstream.

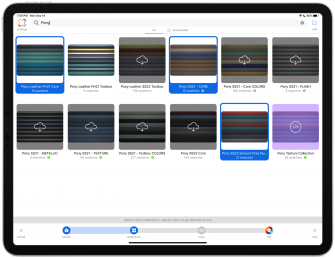

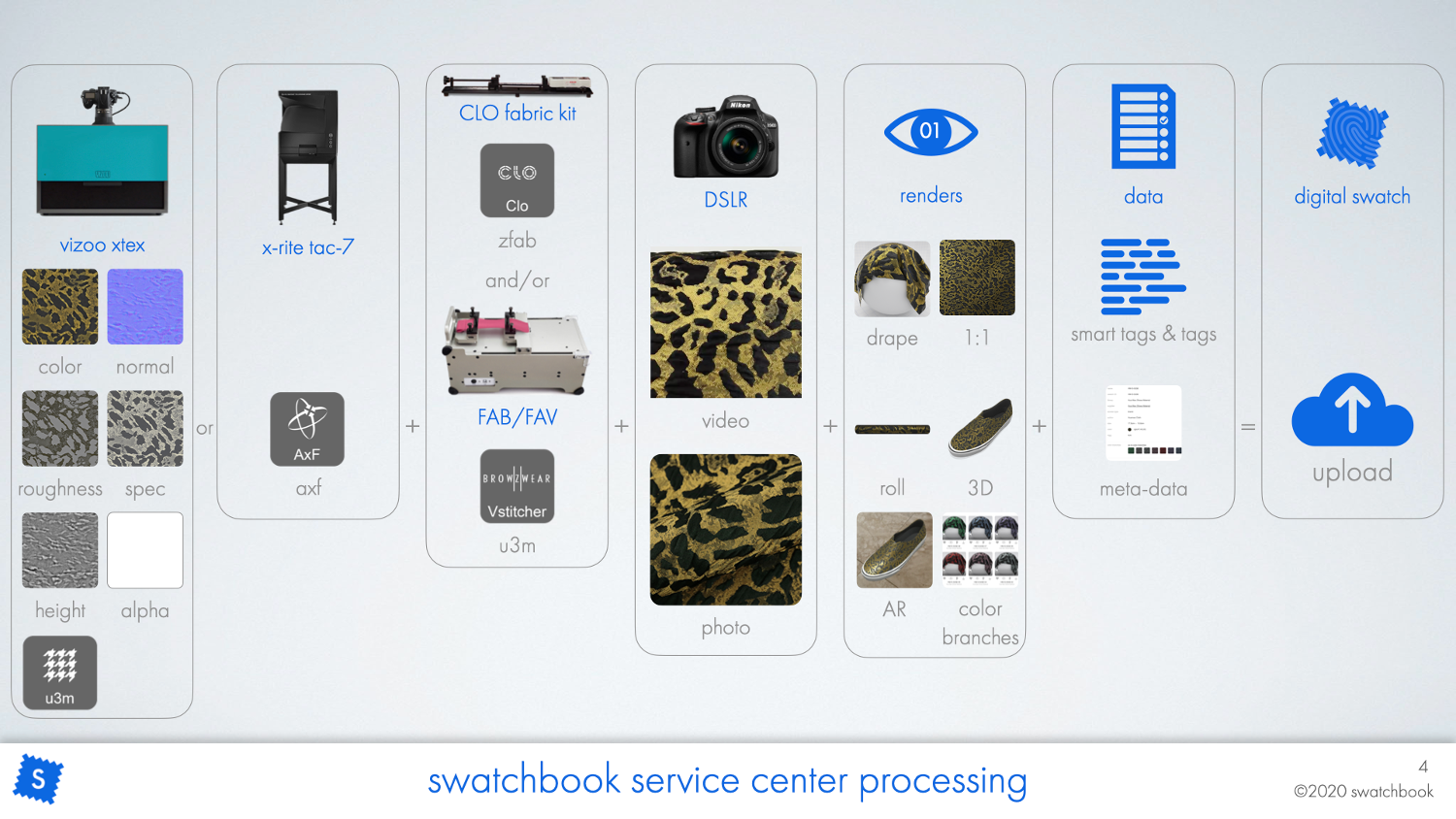

But how does that material get captured? This is an area where Swatchbook has made great strides since we last covered the company. It has established a servicing centre in China that can take material samples and create the assets needed quickly and very cost effectively.

Assuming you are a subscription customer, for the princely sum of $15, you can have a swatch scanned using a Vizoo scanner. Visualisation materials and textures are prepared for use in rendering systems and assets are created for Swatchbook’s library, such as demo videos that showcase, for example, how the material moves.

We’ll walk you through that process in more depth shortly, but it’s worth noting that using China as a location for this service centre means prices are kept low and the centre is within easy reach of many of the major material suppliers and manufacturing centres.

Alongside material data generation, Swatchbook has been doing some interesting work on how it presents the information provided to it by suppliers and clients. The system focuses on presenting materials as they would appear in the real world – not giving an idealised view, but a realistic one.

Even on mobile devices, materials are shown at 1:1 scale. The system works out your screen size and uses that as the base scaling value, a capability the Swatchbook team has patented. Viewing tools have been expanded, so that alongside the roll view, you get a number of draping visualisation methods and the ability to show views of how the material moves.

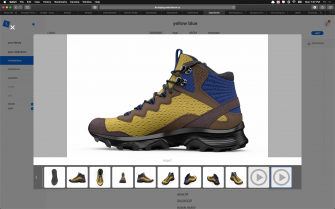

Finally, the Swatchbook team has also expanded the range of visualisation systems supported. The goal here is that if you have a material in your library, you should be able to very quickly use that material in your visualisation processes.

In terms of formats supported, this starts at a base level with texture maps; also encompasses standardised formats such as AXF; and expands to include support for a growing range of applications. These include KeyShot, Modo and Octane, as well as Adobe Substance, Unity, Unreal, Vray and Vred, and moves on to more specialised systems commonly used in the soft goods design workflow, such as Clo3D/ Marvellous Designer and Vstitcher.

CMF exploration with Swatchbook Mix

All of this work has culminated with the release of what will take up the greater part of this review: Swatchbook Mix. I’m going to step through how this is used and, along the way, that should bring out a true sense of its purpose.

Let’s start with a little thought exercise and consider this scenario: you have a digital model of the product you’re working on, but you want to experiment with different colours, different material choices and different styling options.

In many cases, you have a number of materials that your team has decided on for that season, for that geography or for some other reason. Within Swatchbook, these would be organised and grouped under a ‘collection’.

In a traditional workflow, you’d be working with physical prototypes and digital renders, along with physical samples and swatches, to try and extrapolate combinations. That’s a lengthy process and one that comes with a number of limitations – physically, financially, mentally and organisationally.

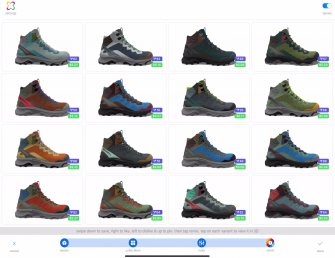

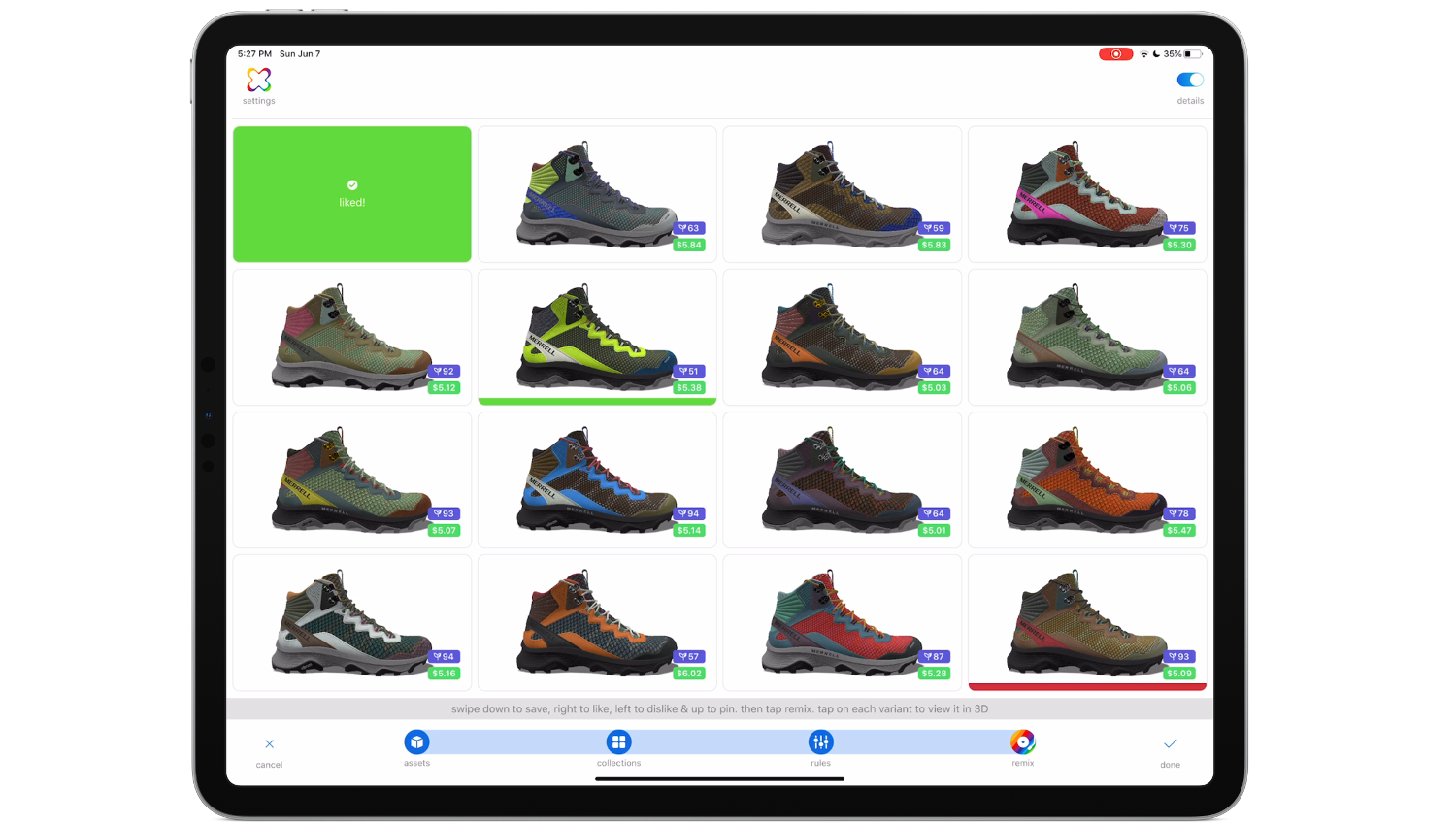

Instead, imagine adding in a few rules about how and where those materials should be applied to your digital model, then having the system start to churn out possible combinations. This happens not manually, but automatically, according to your predefined rules, and providing you with a huge number of options. All possible variants are presented on screen in a grid, with thumbnails of the size you want.

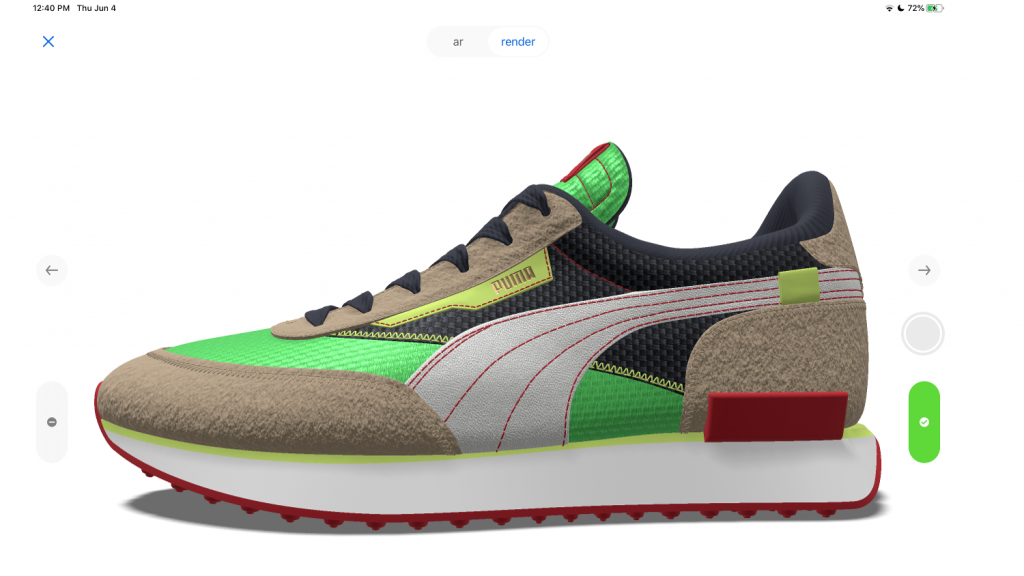

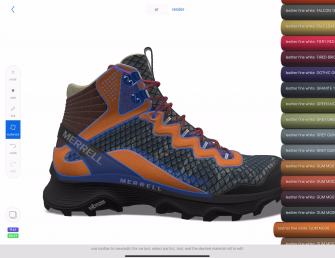

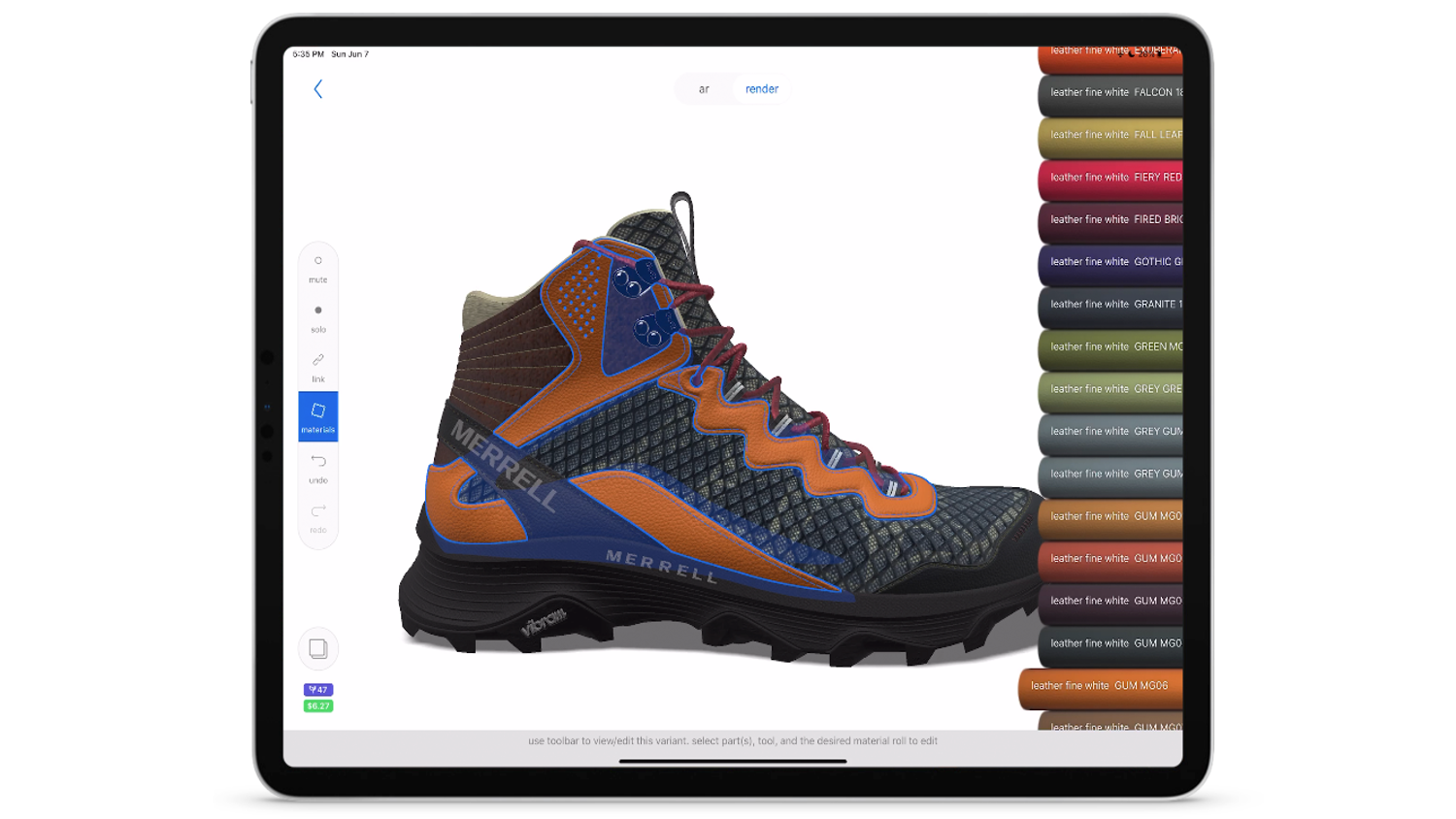

These variants can be quickly dismissed with a swipe (left for no, right for a design direction you like) and more can be generated. If you want to dig deeper, you can engage with a variant, dive in, rotate a realistic model of how the product looks, select or reject it, tweak it.

If you want to see how it looks in the real world, you can flip it into augmented reality (AR mode) and position it in front of you. Alongside this, because your material definitions are based on realworld supplier metadata, you can access additional information, such as rough cost, geographic data, sustainability impacts and more.

It’s worth noting here that sustainability data is based on the composition of the material and Swatchbook uses publicly available data from the Sustainable Apparel Coalition to calculate its HIGG-Index rating.

Suppliers and brands can provide their own sustainability data if they have it and add this to the material in place of the data that Swatchbook provides by default.

In this way, in the space of a few short minutes, using Swatchbook Mix your team can uncover new combinations of materials that it might not have considered, explore how a product or product range might look using that material, generate a set of actionable data for further exploration with a BOM, and the assets are all ready to be pushed into visualisation processes that rely on other systems. Now imagine all of that working on an iPad Pro.

The goal here isn’t to replace the highly specialised skills that industrial and product designers have to offer. The goal is to augment those skills with a set of tools that can rapidly generate design concepts using a set of inputs.

This is by no means an entirely new idea. In the engineering world, this type of work is typically conducted using simulation technology for structural optimisation, based on different materials and physical loading conditions (for example, in Fusion 360). Here, we see much the same principle at work, but instead applied to colour, materials and finish.

Just as this article went to press, Swatchbook also announced it is adding a cloud-rendering service through Otoy’s RNDR service, so you can render your variants or entire ‘mixes’ directly from your iPad Pro. It pushes a variant into the RNDR cloud, and returns 10 views plus a turntable (24 frames) that will be stored inside of Swatchbook along with the variant.

In conclusion

Swatchbook Mix is a unique offering and the way that the team behind it has approached its development shows a deep understanding of the needs of the audience it is targeting – far deeper, in fact, than many other organisations could muster.

The analogue nature of traditional material specifications processes – supported by physical samples and cobbled-together spreadsheets – no longer suits the speed at which today’s industrial and product development specialists work. They need something more organised, more shareable and more centralised.

Going fully digital makes huge sense, especially when you consider the rapid move towards more distributed ways of working and the vast geographic spread of modern supply chains.

In summary, the work that the Swatchbook team has done to flesh out its service offering, in terms of material capture, scanning and preparation at a reasonable cost, and to launch the Swatchbook Mix tool for exploration, rapid experimentation and conceptualisation, is first class.

While Swatchbook Mix is clearly aimed at the retail apparel and footwear industry, the tools it has built are applicable to a far wider product development audience.

If CMF specification and management forms part of your team’s work, there are some unique and impressive tools here that are definitely worth exploring.

Workflow: From digital 3D model and material data to CMF exploration & variant iterations with Swatchbook Mix

How to: Exploring Swatchbook’s capture service centre

A digital material goes way beyond what designers have been accustomed to working with for decades. According to Swatchbook, it can’t be fully represented by a spreadsheet, a dataset, an entry in a PDM or PLM system, a shader or a photo.

Instead, the Swatchbook team believes that the definition of a digital material should adhere to a new standard – one it calls ‘digital twin’. It’s a term borrowed, of course, from the whole concept of Industry 4.0. This digital twin, Swatchbook argues, should provide a more exhaustive list of material characteristics. These include:

Visual characteristics: How the material looks, in both 2D and 3D, and in true scale.

Physical characteristics: How a material behaves, when it moves, for example, or is draped.

Metadata: Supplier information, including pricing, composition, availability, minimum order quantity, as well as sustainability scores.

Custom data: Any additional data a user might want to store, of any type and in any format.

With this in mind, a true, digital material, fit for use in 2020, is not a ‘file’ in the traditional sense. It is instead a digital asset, a source of truth that contains four layers of information, which can then be compiled and utilised by any 2D or 3D application. It’s a material with solid links to a supplier, which can sourced just like any physical material.

In order for the physical material to turn into a digital twin, the digitisation process has to be performed correctly. And, given the hardware and software options currently available to do this, the process is typically neither cheap nor easy.

It’s therefore of the utmost importance, Swatchbook argues, that services aimed at turning a material into a digital material as defined here are provided by experts equipped with the appropriate hardware, software and knowledge to assist suppliers in the digitisation process.

Leaving the task up to the supplier at this point in tech history could easily result in frustration and failure for both suppliers and brands.