We meet founder of 3DEngineers, a specialist in taking the dreams of its customers from idea and sketch to reality

Al Dean heads into deepest, darkest Dorset to meet Stuart Brown, founder of 3DEngineers, a specialist in taking the dreams of its customers from idea and sketch to reality by blending traditional techniques with cutting edge technology

Take one technology editor with a fear of speed, place in the passenger seat of a topless two-seater sports car, accelerate to 130 miles per hour on rural private roads and watch what happens as the driver gleefully attacks 90 degree corners without a care in the world, or indeed, a care for the laws of physics.

While hurtling towards certain death that autumn day I realized three things. Firstly, you don’t know how to drive until you’ve experienced taking a corner sideways on cross plies (to quote: “they make it more… slippy”). The second is you become conscious that your body can produce more adrenaline than you ever believed possible. Lastly, you discover that said adrenaline might be brown. But we’re jumping ahead of ourselves, let’s back track to why I found myself in the midst of a near death experience.

The Mitchell Special Mark II: a modern classic and

true original sports car

I had driven down to Dorset to meet Stuart Brown, founder of 3DEngineers, a company specialising in the re-creation and restoration of vehicles. Having taken a year off from a well paid but unrewarding career in insurance, he decided to embark on an entirely new profession.

Modern technology can help solve the given problem without losing the hand-built element that is required

AdvertisementAdvertisementStuart Brown, founder of 3DEngineers

Engineering and design hadn’t featured in Brown’s life until a chance conversation with a friend who was looking to buy an Aston Martin DB4. “To keep money coming in I was doing a bit of eBay automobilia trading and by chance had the full works parts manual for this car,” he says. “Although it’s really expensive, most of the body parts were dead simple shapes so I came up with the ‘Blackadder’ line – ‘Why don’t you make one?’ – for which my friend considered me a lunatic and then promptly went out and bought one.”

While the Aston has since spent much time on the back of an AA recovery van, the idea of making a car got Brown interested in the new possibilities offered by design and engineering. He wondered whether it would be even possible but he wanted to find out exactly how to go about it.

Changing lanes

Talking to Brown over a Scotch egg and a pint of bitter in the local pub, it’s clear he’s a man that likes to do things properly. Although his enthusiasm certainly makes up for his lack of background in the subject he nevertheless decided that before he embarked on any engineering or design work he needed to get up to speed with the technology.

He went through several software packages before settling on his ideal tool-set, which includes Geomagic Studio, SolidWorks and Modo, and then chose to get properly trained up in them.

“Experience had taught me that loads of people claim that they are top of their field, but proportionally not many bother to take exams and courses,” he says. “At the outset, I bought a SolidWorks ‘Training Passport’ that entitled me to undertake every course and the CSWP exam. It was the best thing I ever did in that I learnt the program the proper way, met fellow SolidWorks people and walked away at the end of the year with a qualification that at that time only 101 people in the UK had.”

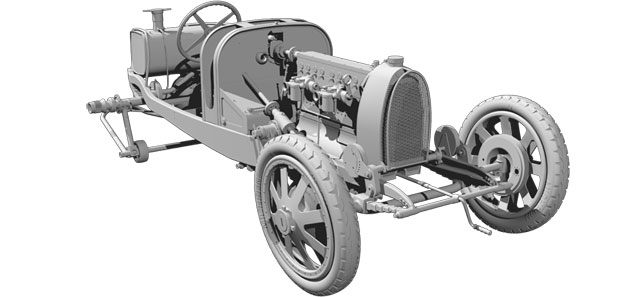

Brown has since taken this further and, despite working full-time, he is currently in his third year of studying for a Bachelor of Engineering (BEng) in Manufacturing. It is also clear that he is something of a bibliophile with a vast collection of textbooks, rare books and manuals that all detail various hand build techniques and the way products used to be created. He is a man who likes to learn from the past and then apply this knowledge to more modern technology and methods. This is exemplified in his chosen Halo project, a complete digital model of the iconic Bugatti Type 35.

Bugatti Type 35 – modelled entirely in SolidWorks and rendered using Luxology’s Modo

The Halo Project

In order to model the classic 1920s sports car in its entirety Brown would need some help. “Having only made a chassis rail in Rhino, I visited The Bugatti Trust with a couple of renders and managed to persuade them to help me undertake the task,” he explains. “After a few months of buying the plans to re-create the parts, they realised I was serious and so sent me them free as required.”

With the blessing of the Trust, Brown then began the mammoth task of working through all of the documentation and building a complete model of the car in SolidWorks. Having seen some of the drawings first hand, it’s clear that these are technical illustrations par excellence for the period. Although fully detailed in beautiful script, which you won’t find anywhere today, time has unfortunately taken its toll on many of them.

In terms of the modelling process, Brown underestimated things a little, “I thought there would be about 600 parts in the Bugatti; there were 2,800,” he explains. “In the course of undertaking the project, I had to tackle every type of SolidWorks problem there was. This is something I would not have experienced in years of working for a firm, as CAD jockey remits tend to be narrow. The previously mentioned training massively helped when faced with a seemingly insurmountable problem.”

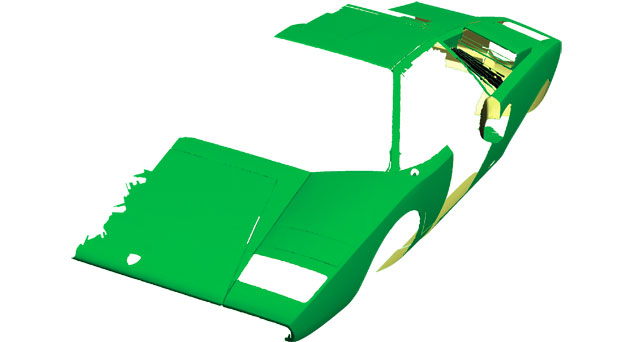

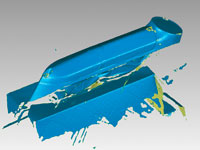

Capturing A class surface data repair, restoration and archiving – screenshot from Geomagic Studio

Finding a niche

Since the Bugatti project, which still continues today, Brown has built up something of a reputation amongst a select set of customers in the automotive restoration field. Much of this is down to his diverse skill set, as Brown explains, “It’s not uniquely CAD, nor scanning or engineering,” he says. “It might be art at times and it might be completely unglamorous when scuffing around on an oily garage floor in the middle of nowhere with the doors wide open with snow falling outside.”

The work Brown undertakes ranges from pretty bog standard reverse engineering jobs through to helping to restore many classic and extremely expensive vehicles, from Lamborghinis to Ferraris and beyond. He has even helped in the remanufacture of a body panel for one-off Jaguar prototypes.

Alongside the automotive work, Brown has found his skills called upon by restorers of musical instruments, helping them to use reverse engineering techniques to get through the product phase and into the art of violin making more quickly than using traditional techniques.

But for anyone that’s spent five minutes in the passenger seat with Brown, it’s clear that cars are his passion. This can also be said about many of his customers, one of which is Andy Mitchell of Mitchell Motors, a firm that specialises in the restoration of some unbelievably exotic pieces of motor history.

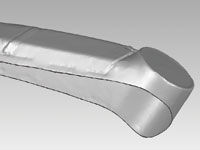

The Mitchell special mark II

Like Brown, Mitchell loves fast cars, but with the procession of classic vehicles that come through his facility he has built up a strong desire to have something truly original, something that satisfies both his love of racing and his very specific views of what makes a good looking vehicle.

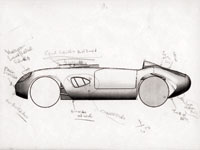

At his first meeting with Brown, Mitchell handed over 100 photos of cars, 50 of which he liked and 50 that he didn’t. His only stipulation was, “I don’t want a munter.” Brown then went to work on creating a true original.

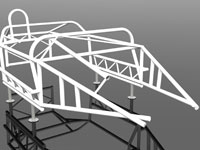

With the engine sourced from a Bristol and the chassis built, Brown began with basic design sketches to get an idea of what his customer wanted. Once a basic shape had been decided upon, the two worked together to fine tune the design. Brown used the surfacing tools in SolidWorks and rendered up design candidates using PhotoView 360 for Mitchell’s approval. Once this was finalised, rapid prototypes were built to give Mitchell a good solid idea of where things were headed.

The next stage was the development of the buck. A buck is a former/tool which a body maker uses to obtain the shape of an item. Generally they would start with a flat sheet of material and converge by referencing the buck to the correct shape.

“It is one of those tasks that on the face of it appears relatively straightforward, but in reality for a whole variety of reasons is difficult to do,” explains Brown. “It is very easy to paint yourself into a ‘virtual corner’ when creating them.

“To create a buck many advanced SolidWorks techniques are required as well as access to other programmes and techniques such as Geomagic Studio, scanners and a great deal of awareness of traditional methods.”

Once Mitchell had taken delivery of the buck he began to use his rather specialist skills to hand fashion the body for the car. The team took the project from conceptualisation to reality and indeed, racetrack, in just seven months and the car is now competing in vintage car competitions – and frankly is an incredible piece of work.

Back to the future

According to Brown, his job involves bringing together disparate techniques to help solve real world problems.

With a mix of both new tools and old techniques, he has an interesting take on what is the most critical part of his job. “Finding the people and literature to learn dying techniques, so modern technology can help solve the given problem without losing the hand-built element that is required,” he explains. “To this end, I have a network of people to call on and have acquired, at ridiculous expense, many rare books and manuals detailing the way products used to be created.”

He also realises the importance of learning directly from the source and recently took time away from the computer to work at a classic car restorers to get a feel for the problems the people on the shop floor had to contend with. “Tea with the workers is a great way to find out what they hate and like. They will be using my creations after all,” he smiles.

www.3Dengineers.co.uk

Bringing the Mitchell Special Mark II to reality

1. Handed 50 pictures of cars the client (Mitchell) liked and 50 the client hated, Brown was tasked with the challenge of creating a one-off car that looked like none of them but was in the spirit of a 1950s racing car and wasn’t “a munter”

2. Information was then gathered including books and manual measurements from the existing chassis and engine. A model was then mocked up in SolidWorks in order to ensure the body would fit OK

3. Mitchell’s favourite image. He loved the thought of being involved with the shape from the very outset. Being simple – it can hardly even be classed as a render. This was a bonus as they could concentrate on the overall shape

4. The final design is modelled up and rendered (using Modo). Rapid prototypes were also created with help from Laser Prototypes in Ireland to give the client assurance that the final product would match expectations

5. A buck (wooden former used to create car bodies) was designed. Consultation with the people creating the vehicle is key to ensure their specialised requirements are met as these are highly skilled craftsmen

6. The Mitchell Special Mark II was completed in April 2009 meaning that from start to finish, it was created in 7 months. The car is now competing in classic races and you can follow its progress here

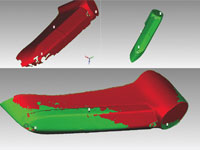

Reverse engineering a Jaguar XJ13 rear light cluster

A. Jaguar XJ13: a one-off racing car developed to race at Le Mans in the mid-1960s – 3DEngineers were approached to rebuild a headlamp cluster. Photo Credit: Mike Morrin

B. Scanning preparation includes matting the surface, masking sensitive areas and location dots added – the item is then scanned using a CreaForm HandyScan

C. Due to the nature of scanning, a single part can require multiple scans to create a complete representation of the part in question – here those raw files are in Geomagic Studio

D. These are then joined (registered) and cleaned up, smoothed and enhanced in Studio which 3DEngineers relies upon and can’t recommend enough

E. In this case the curve where the part meets the vehicle bodywork is key and can be exported to Solidworks using Geomagic’s parametric exchange function

F. Final component remanufactured and ready for use. The benefit of the process is that it’s possible to create data for a one-off prototype that’s worth an estimated $20 million

We meet the founder of 3DEngineers, a specialist in taking the dreams of its customers from idea and sketch to reality

No