The Canary is a smart, distinctive home security device for the Internet of Things (IoT)

Everyone should feel that their home or workplace is safe and secure, even when they’re not physically there to check up on it. That’s the thinking behind Canary, a smart security device that keeps homeowners and tenants connected to their properties, via their smartphones, and alerts them to any potential problems.

A mobile app notifies users of any unexpected activity picked up by Canary’s motion sensor. It enables them to watch real-time footage of their home, captured on its high-definition camera. It allows them to sound the device’s 90-decibel siren, with just a swipe of their finger, in order to scare off intruders. And Canary also provides a stream of data to the app, relating to air quality, temperature and humidity in the user’s home.

In short, there are a lot of bells and whistles packed into this sleek, minimalist product.

Perhaps unsurprisingly, Canary’s already been a hit, raising almost $2 million in pre-orders from its Indiegogo crowdfunding campaign and shipping 10,000 units to 78 countries worldwide in just over a year. Today, less than one year since its retail launch, the product is available in over 7,000 retailers in the US, UK and Canada, including Apple, John Lewis and Maplin.

Success stories, meanwhile, are already rolling in from Canary users and available on the company’s YouTube channel. One woman, Melaney, received an alert of an unwanted intruder in her home while she was out at work and notified the police.

When she showed them the video that was captured by her Canary and backed up to the cloud, the police instantly recognised the burglar. He was in custody within 24 hours.

As with many great products, the idea for Canary came from personal experience. “Myself and my two co-founders live in New York City,” says Canary chief creative officer Jon Troutman. “We’d all had similar experiences of that feeling of vulnerability when you leave your home to go on a trip and not know anything about what’s happening at your home or apartment while you’re away.”

Canary CEO Adam Sager envisaged a security device that anyone could purchase straight off a store shelf and install in their own home, without the need for particular technical expertise or assistance.

This product, the team decided, shouldn’t be a hassle, should be smart enough to learn and adapt to normal activity patterns in an individual home and should be the kind of good-looking, stylish object that would appeal to a house-proud and design-conscious customer.

Troutman continues: “The idea is that we would build a product that allows people to be more connected to their homes, to allow them to go out and be more fearless in their lives, because they don’t need to worry about what’s happening in their homes thatshouldn’t be [happening].”

Canary’s service combines a hardware device and a mobile app to enable customers to monitor their homes and workplaces while they’re on the go

Form and function

From the start, the team behind Canary were adamant that form and function should share equal billing.

That’s why they brought in as a consultant James Krause, who was working for Motorola. (He was eventually lured away from that job to take the full-time role of lead industrial designer at Canary.)

The first iteration of the formative design that he came up with for Canary was “ugly but functional”, according to Troutman, but the process of refinement quickly got underway.

“A guiding principle for us was that [Canary] needed to be a beautiful product. It wasn’t the case that we worked out the tech and then worked out what plastic we could wrap around it, which is how a lot of connected devices are designed.

This was never going to be a purely functional product.”

“We think of the home as a place that’s almost sacred. It’s your personal space and you want to feel as comfortable as possible there, so this was as big a design challenge as you can imagine. We had to ask ourselves, ‘What sort of form factor camera do we have to build that’s going to make you comfortable when you see it on a shelf or on a wall?’,” he says.

As a result, the Canary team considered form as critically as it did the technology that powers its device. “We went through a lot of rounds of sketching and figuring out what sort of form this could take that wouldn’t look like a camera, [that would] have some other shape that didn’t scream, ‘Hey, look, there’s a camera on the shelf!’, that would look like an object.”

With that in mind, a purist cube shape was one of the options explored. Other versions were inspired by The Gherkin tower in London, the building more formally known as 30 St Mary Axe. Eventually, the team settled on a cylinder-like form that went through a dozen or so prototypes.

In terms of the design tools used, the team at Canary relied on Alias for product design, NX for engineering and KeyShot for visualisation. Early prototypes, meanwhile, were built on a Makerbot, then as things progressed, more accurate SLS prototypes were created on a Shapeways machine.

“We eventually got to the rough look we wanted. Then it was months and months of hammering out all of the details,” Troutman recalls.

Canary went from prototype to mass-produced device, delivered to backers’ homes, in under 12 months

Manufacturing plans

As the design details started to take shape, the team began to consider manufacturing options.

They quickly came to the conclusion that, here, independent advice would be invaluable. Says Troutman: “Similar to our experience with industrial design, early in the process, we found a group of people who we contracted to help us with manufacturing and production and things we didn’t have experience with.

Then, as we grew, we either hired them internally or found someone else to fill the role.” The company also worked with Dragon Innovation, a New York-based consultancy that specialises in advising start-up businesses on ramping up production in the Far East.

“They helped us with navigating the process of manufacturing overseas. Once we’d got a little further down the road, we hired people to handle it and run that process [internally],” says Troutman.

“That’s really important when you’re starting out – to not try to do everything yourself,” he advises. “Recognise where your strengths are and where you need help, then be smart about the order in which you hire those skills internally.

You can work with outside help for a little while, but eventually, it makes sense to bring those skills and knowledge inside.”

Appeal to the cloud

The next logical step on Canary’s journey was a crowdfunding campaign on Indiegogo.

While the company had already received some seed funding from investors, it saw real benefits to this route, says Troutman.

The first was the validation of its idea; the Canary team believed in its idea and saw it as a big opportunity – but they wanted to test to see if the market felt the same way about it.

The second benefit was speed to market. “Indiegogo was a good opportunity for us to move a little bit quicker,” says Troutman.

In the event, an overwhelmingly positive response took even the confident Canary team by surprise. “Within the first day, we knew it was a good idea and that people were going to buy. It was about as exciting as you can imagine and exactly the outcome we hoped for,” he says.

“As soon as [the crowdfunding campaign] went live, people all over the world were clamouring for [Canary] and offering their support, both in terms of ordering it, as well as starting online conversations around how smart home security is consumer-friendly.

We felt that validation and it catapulted us forward.” Looking back, Troutman sees both positive and negative aspects to taking the crowdfunding routes.

On the plus side, he says, you rapidly have a community of supporters, backing your idea and contributing their ideas and opinions. “We had all these people cheering us on as we were building this product – and the feedback we got was amazing and incredibly helpful in building the right product, out of the gate.”

At the same time, he adds, it’s a lot of pressure. “Pressure is good, but [crowdfunding] adds this pressure that says we have to deliver this product and, when we do, it needs to be everything we hoped and more.

That pressure is a big motivating factor for us and the team, [but] it’s also scary.”

Canary founder and CEO Adam Sager

Hardware/software convergence

Canary is typical of a new breed of so-called ‘smart product’ that’s only just started to emerge in recent years but is expected to quickly become widespread.

With its connectivity, built-in sensors and embedded processing capabilities, it’s engineered to play a part in the Internet of Things (IoT) – and, as such, its development will be of interest to other manufacturers intending to take their own products in a similar direction.

In particular, this development work involves software just as much as it does hardware and industrial design.

From talking to Troutman, it’s clear this is a subject that the Canary team takes very seriously. “We try to think of the hardware and software as one and the same,” he says.

Jon Troutman, co-founder and chief creative officer at Canary

“What’s interesting about Canary is that you don’t really interact with the device itself after you’ve set it up. From that point onwards, all of your interaction is with the app on your phone.”

That said, Canary wanted to engender in users the same enthusiasm about the hardware as they feel about the software, he says. And, at the same time, they wanted to build a product that would blend into a home, rather than sticking out like a sore thumb, as most wireless routers seem to do.

“We do some interesting things with the hardware. For example, [consider] how we treat lights on the devices: it’s not one of those products that you have in your house that has a blinking light to show that it’s on. Canary is a very thoughtful device, [one] that’s trying to be friendly and give you a soft feeling in your home. So the lighting isn’t harsh.

Canary founder and chief technology officer Chris Rill

There’s a soft glow that comes out from beneath the device. These little details are important to us.” In the same way, he adds, the mobile app is designed to fit into users’ lives and daily routines, in the same way that the hardware fits into their homes.

“As we were designing the hardware, we were designing the software at the same time, with the same team. We didn’t outsource that at all. That results in an inherent link between how we thought about the two aspects of the design,” he says.

Where next for Canary?

After an indisputably successful first couple of years, Canary now has a strong brand and a product that can be found in thousands of homes. Where does it go next?

Geographic expansion is a big focus, says Troutman. “The future for us is about continuing internationally. We launched in retail first in the US, then we went into the UK and we’re going to continue to expand into new areas.”

Canary’s team used Siemens NX, Autodesk Alias and KeyShot to develop the device

Integration partnerships are also on the cards. Canary has recently teamed with a company in the US called Wink that provides integrations that enable users to connect up different smart products within their smart homes. “Based on listening to our users and hearing what sort of things they want to do with Canary, Wink provides a good way for us to do that,” he says.

And customers can certainly expect new iterations of the Canary device, a process that its inherent connectivity makes easier, he says: “We’re always thinking about how we make this product better and, because it’s connected, it can easily be updated through firmware.

We’re constantly making improvements and the product is getting better, based on listening to our community and working out what will make Canary more empowering for them.”

Want to join the revolution

DEVELOP3D asked Jon Troutman, chief operating officer of Canary, what advice he would offer to other start-ups looking to penetrate the connected device market. He gave two tips, based on his experiences at Canary:

1. Consider the human perspective

“It’s key to not think about a connected product [in terms of] connecting to other products or to the Internet. Some people say, ‘Oh, I want to build a connected product or something for the Internet of Things.’

“I think the more important questions to consider are these: ‘How will this interact with a human? What’s the relationship that will be built between the person and the product?’

“If there isn’t a good, obvious answer or story about why someone would want to interact with that product, then I think you have to stop, go back to the drawing board and figure out what the engagement factor is and why someone would need this.

“A lot of connected products fail in that respect, in that they seem exciting at first, but once someone sets them up, they don’t want to continue using them, because they don’t add enough value or provide enough engagement.

“Ask yourself: ‘How can this product be engaging? How can it be valuable? How will someone want to interact with it past the first day?’”

2. Don’t try to do it all

“Avoid doing too much – it’s easy to fall into that trap.

There have been times when we’ve had a million ideas and we’ve thought, ‘Oh, let’s do all this stuff.’ We’ve had to continually pull ourselves back and say, ‘Do we want to take on ten things, or do we want to take on two things and hit those out of the park?’

“There’s enough technology that’s available and enough components that are cheap enough that you can do [almost anything]. You could build a product that’s a Swiss Army knife that does a million things, or you can build a product that fills a particular need and focus on solving that need well.

“If you fall into the trap of trying to do everything, it’s a lot harder to succeed. Be really harsh with yourself and force yourself to turn down certain ideas or put certain things on hold and focus, focus, focus on what’s going to provide the most value.”

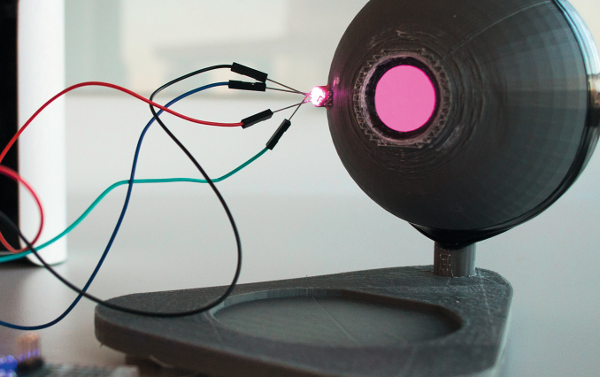

The Canary team have created a small, cost-effective integrating sphere for testing, using some custom code, an Arduino and a Makerbot

Building your own rig

During the development of its final product, the Canary engineering team came across a challenge.

The device uses an ambient light sensor to enter and exit night vision mode. (Other consumer products that offer night vision tend to rely solely on their camera to do this.)

As a blog post about the issue explains, “Though every Canary is equipped with the same kind of ambient light sensor, there can be a wide variation in light response from one sensor to another.

One of the engineering challenges our team has been working through is refining the embedded software for our ambient light sensor, to better account for these variances.”

Canary’s ambient light sensor is a phototransistor, a semiconductor device that acts like a valve to regulate electron flow (or current) proportionally to the photon-flux (or light) that hits the sensor area.

This ambient light device and electronic circuit is quite sensitive and is set to measure light up to 150 lux, which is sufficient for a home environment.

(As a reference point, in a typical family living room, illumination is about 50 lux.) The Canary’s sensor is linear in this range, which is another way of saying that its read-out is proportional to the amount of light.

The design process therefore required the team to ensure that the sensor was exposed to a known level of illumination during testing, which typically requires a large and costly piece of equipment known as an integrating sphere.

To get the same results, the engineering team developed a home-brewed solution using some custom code, an Arduino and a Makerbot.

As an added bonus, it open sourced the whole project, so more details and a peep at the schematics, the 3D print files and the Arduino sketch can be found here.

Jon Troutman on the design and development of the smart home security device

Default