Having launched their first product, Invenire, the founders of Apiar speak to Stephen Holmes about the journey of discovery they’ve been on to build a luxury watch brand from scratch with real engineering at its core

Luxury watches from companies such as Rolex, Cartier and IWC are always compared to cars, planes and boats, says Matt Oosthuizen. As co-founder of burgeoning timepiece start-up Apiar, he wants to think differently. “We thought: why can’t we have resemblance to the cutting-edge engineering that additive manufacturing is providing? The same lattices that you would see on the nozzles that NASA is using with internal gyroid structures?”

In short, he’s as passionate about digital manufacturing as he is about horology. In a world of watch collectors, where exclusivity and back-stories are key factors in the perceived worth and desirability of a product, Apiar has picked a unique angle with which to break into the market.

It has a commitment to UK production and sourcing, which goes hand in hand with another pillar of its values – sustainability.

But what truly sets Apiar apart from other vendors is its approach to digital design tools and additive technology – not simply to create new designs, but also to offer an unparalleled level of customisation and exciting material choices at a price that can’t be matched using traditional manufacturing.

When milling a watch body from a billet of metal, price differences between materials such as stainless steel and titanium are considerable. But to 3D print the same form in both materials is a much smaller leap in cost.

The exciting thing for watch collectors is that Apiar’s technology-driven path allows for a wider range of exotic alloys to be used.

“We can use tungsten. We can use tantalum. We can use all these super, super hard materials that previously you could make watches out of, but you would go through so many machine tools to be able to create the watch case, that it wouldn’t really be financially viable,” says Oosthuizen.

“People’s point of reference is still stuck in there,” adds his co-founder, Sam White. “They think, ‘Wow, how can they supply a titanium watch for next to steel prices?’ because they don’t know that additive narrows that price gap so much more.”

Inside job

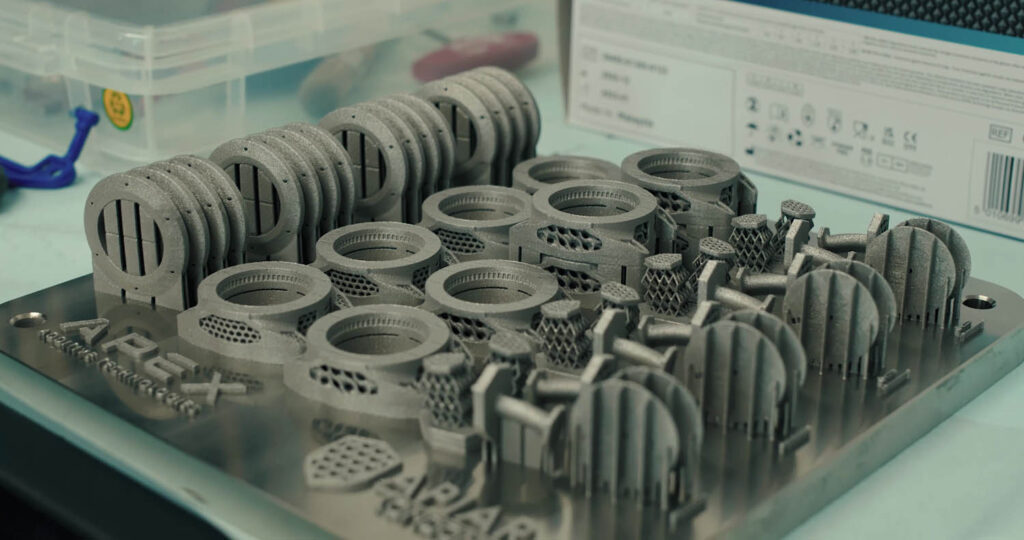

Geometrically speaking, the main feature that sets the Apiar brand apart is the use of latticing. As in aerospace, it allows the company to lightweight the watch using less material. This not only makes a large-body watch more comfortable to wear on a day-to-day basis, but it also adds the ability to make latticing part of the aesthetic.

For Apiar’s first model, the Invenire, customers can tailor features such as the dial and strap through the use of a 3D configurator on its website, as well as the form of the latticing. Thanks to additive manufacturing, it’s “a bespoke product at economies-of-scale pricing”, says White.

Apiar’s founders bring a unique perspective of real engineering to an industry that often leans on the term for effect. Alongside the rigours of building the start-up, Oosthuizen works as a sustainable manufacturing specialist at Autodesk, while White is a mechanical engineer for AtkinsRéalis.

More comfortable with modelling in 3D than sketching, the pair quickly sculpted the case design of the first product and sent it to a desktop 3D printer.

“Going straight to 3D design and leveraging FDM and resin printers throughout the process enabled rapid iteration and testing of the watch’s physical signing and wrist feel within hours, says Oosthuizen.

This approach of ‘failing fast’ was key for Apiar, helping it develop the Invenire from concept to initial metal prototype in just months, with the final design taking less than one year. Says Oosthuizen: “We could implement design changes, test them in resin, and have them printed in titanium within a 24-hour cycle.”

The founders also explain that their mechanical engineering backgrounds lead to designs where aesthetics are closely intertwined with function. “Traditionally, the approach might be to create a design that looks pretty and then make it functional. In our case, we focused on making it functional first and then aesthetically pleasing.”

Autodesk Fusion 360 proved the best tool for the team’s end-to-end product development. “We could design our cases in Fusion, render for initial feedback from our watch collector feedback group, and then send designs to be simulated and manufactured within the additive build extension,” explains Oosthuizen.

For the latticing sections, a mixture of techniques was used, from manual modelling of hexagon patterns, to exporting the CAD model into Autodesk Netfabb for lattice generation, and more recently, using the new volumetric lattice tool in Fusion for the testing and generation of X lattices.

The dials of the watches were also machined using Fusion 360 CAM workspace. Using a compact Datron Neo CNC, Apiar’s dial manufacturing partner Bedford Dials in Tenbury Wells, UK, could accurately machine guilloche dials from brass billets.

The additive element was produced in collaboration with Apex Additive Technologies and its fleet of Renishaw 3D printers. Its location in the former metallurgy heartland of Wales, Ebbw Vale, adds to the British manufacturing heritage of the brand. In fact, the only part to originate elsewhere is its use of a Swiss movement.

Engineering a new way

“The industry keeps its cards pretty close to its chest and as such there isn’t much out there in the way of standards,” says Oosthuizen, as he reflects on the issues of starting in horology from scratch. Having to tackle challenges like waterproofing the mechanism proved tricky at first but drawing on engineering fundamentals saw them through.

“Our engineering backgrounds along with a bit of trial and error helped us to get this right,” he laughs.

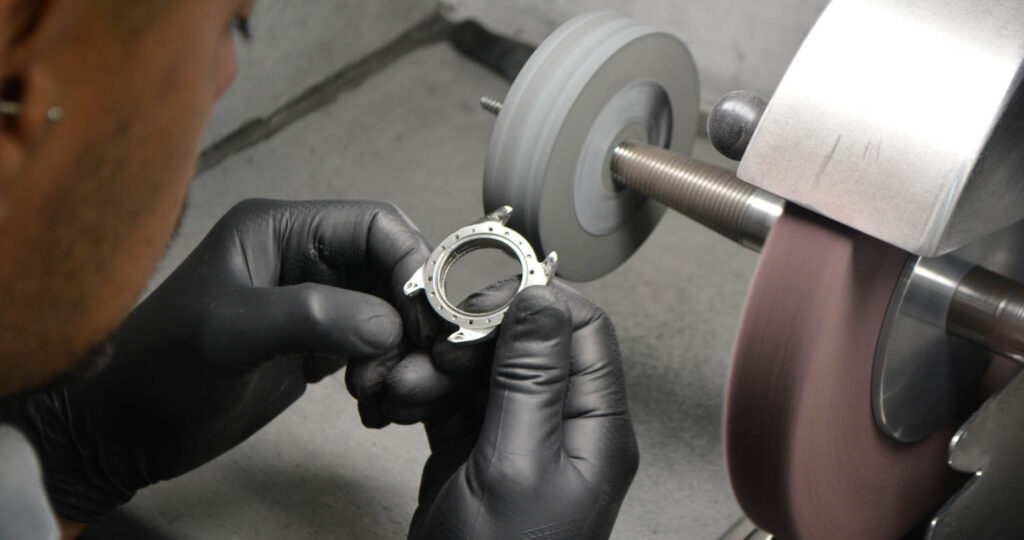

A key issue is the machining of the watches. Apex Additive produces a watch with roughly .5mm excess, allowing it to be machine-finished to the tolerances and finish expected in luxury watchmaking.

The founders admit that it has been difficult to ensure the transition between printed and machined texture is perfect, requiring iterations and workarounds to blend the smooth machined finish and the surface texture of laser-sintered metal powder.

This level of perfection leads back to the online configurator, and making sure all preferences can be achieved.

Currently, the site is focused more on controlled customisation, whereby existing designs can be ‘curated’ by their prospective owners, says Oosthuizen. But the goal is to reach a point where, with a slight element of handholding, a customer can have much greater input – changing lattices, making changes to case geometry and more.

“We’ve got a lot of ideas for what we do next: more ergonomic shapes, generative design, multimaterial printing,” he continues. “Invenire is Latin for ‘discovery’. We want it to be how people discover additive manufacturing.”

This article first appeared in DEVELOP3D Magazine

DEVELOP3D is a publication dedicated to product design + development, from concept to manufacture and the technologies behind it all.

To receive the physical publication or digital issue free, as well as exclusive news and offers, subscribe to DEVELOP3D Magazine here