Connected devices can now be found in every room of the house, from lights in the living room and speakers in the kitchen, to the security camera in the garage and the baby monitor in the nursery. Stephen Holmes meets Zuma, a company building a hardware platform that can incorporate all of these gadgets and more

How connected are you? Be it by WiFi or Bluetooth, many of us are now the slaves of a vast range of smart devices: speakers, lights, cameras, heating controls and even pet monitors.

The more of these gadgets we buy, the more platforms we add and the harder it becomes to operate them all, weighed down as we are by multiple different apps. And that’s without even mentioning the shelf-space needed to accommodate these products, or the inadequate functionality offered by some of them.

Wouldn’t having just one, all-purpose – or at least multifunction – product be less of a burden? A little over three years ago, Morten Warren, founder of Native Design, approached a group of designers at the company’s London headquarters with an idea for his new house – a connected, high-end speaker system, built within the profile of a standard GU10 bulb light fitting, that would also provide lighting.

Over 200 physical prototypes and one new company later, Zuma’s Lumisonic was launched. It now takes up a storefront in the busy heart of London’s West End retail district, where senior engineer Edward Rose greets us in front of a pyramid of glossy packaging.

The first impression is of how much effort has gone into setting up the sensory retail environment. The first room has a dozen Zuma units set into the ceiling. Connected to Rose’s iPhone, all 12 begin playing music in unison, without any hint of lag. A full-bodied blanket of sound, clear and bassy, coats you wherever you stand, while Rose simultaneously adjusts the room’s brightness.

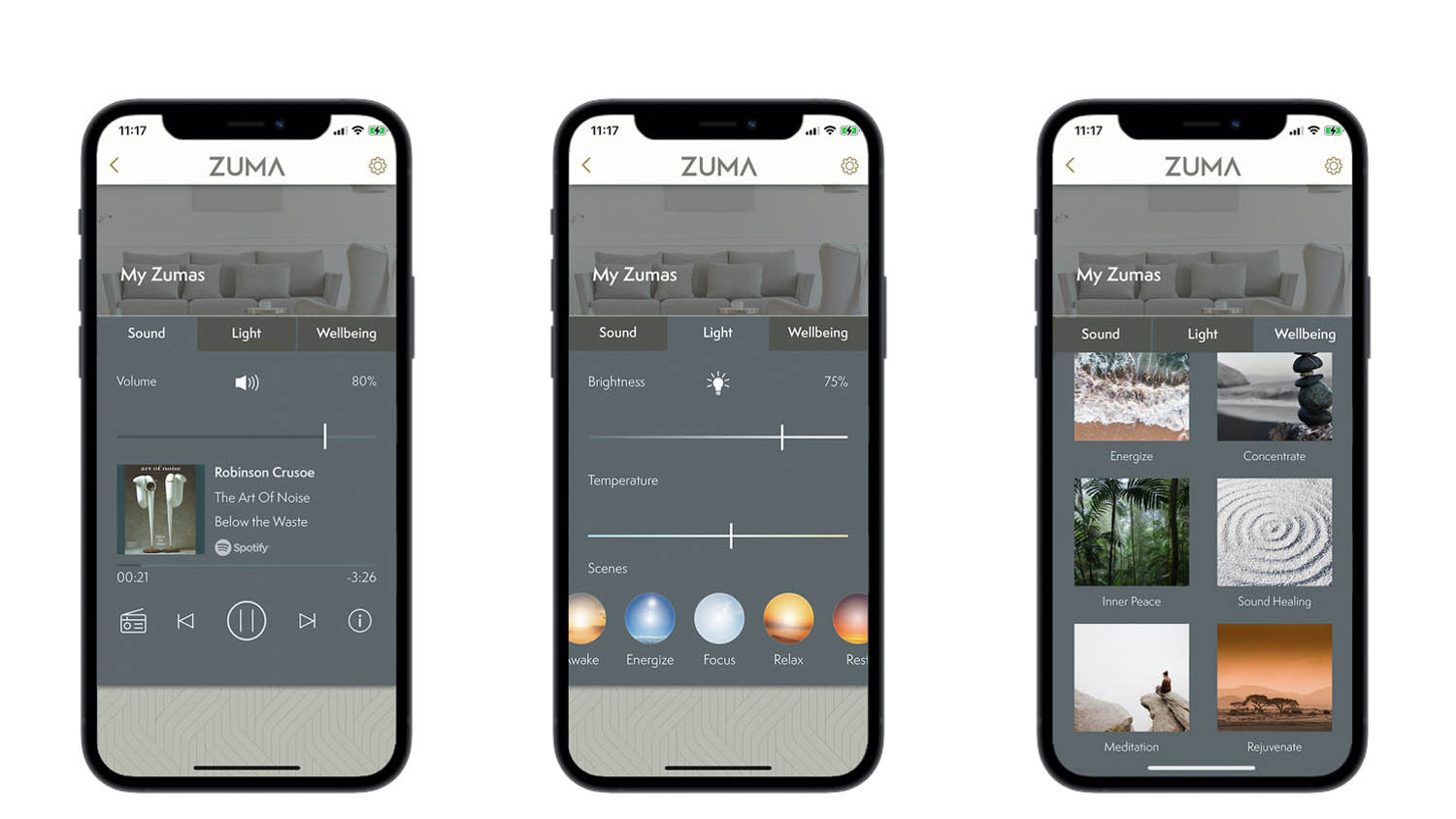

Other rooms showcase the product as part of a home cinema set-up, another as your personal wellness room, with pre-set combinations of ambient lighting and relaxing meditation soundscapes changing the room at the touch of a button.

Everything is slick – from the app interface to the minimalist speaker grilles – and Rose exudes passion for the project, now operating as a standalone business from its Native Design beginnings.

“It’s such a big effort, such a big lift, to deliver a piece of hardware,” says Rose, with a deep exhale. “So, while you’re at it, you might as well make it as full featured as possible and then roll in bits of those features you like best as you develop the software.”

Without that approach, he adds, you would put yourself on a two- to three-year release cadence of producing new hardware and still not cover exactly what customers want.

“By the time you’ve discovered [a need], it’s changing. So, we invested heavily upfront in producing as much functionality in the hardware as we could conceivably get away with, with a view that we can do whatever we want with software.”

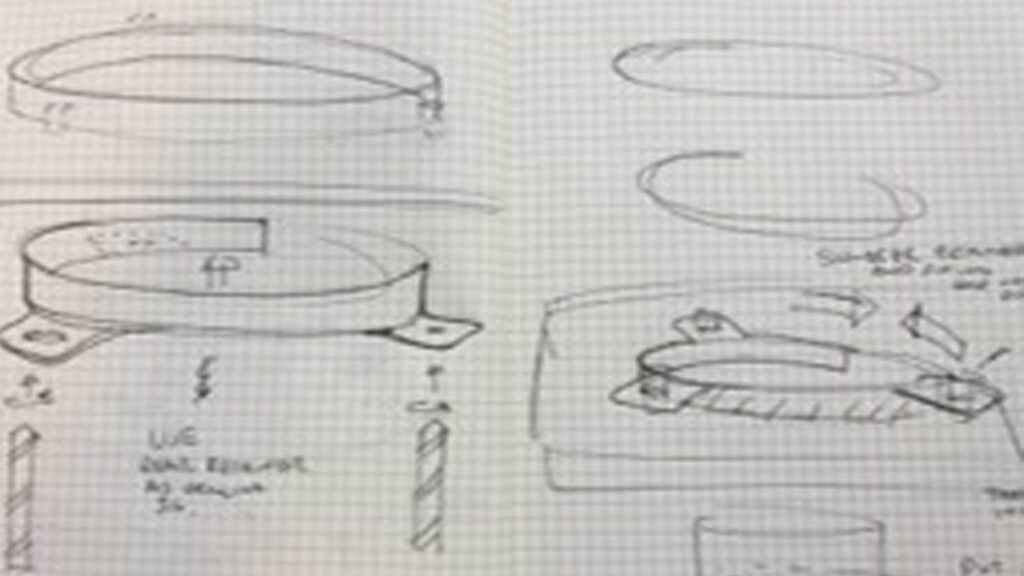

Zuma – Throwing ideas at the wall

The design process for Zuma began with lots of sketching and conceptual prototyping, as no one on the team quite knew what final architectural form the device would eventually take. Every element seemed to play against the other. Heat issues would arise around the placement of the LEDs. Ventilating the LEDs would interfere with acoustics. Running wires would discolour the sound.

Says Rose: “We threw ideas at the wall for quite some time. The fruits of that actually didn’t stick in the end. For one reason or another, all of those variations had a weakness of some kind that we couldn’t overcome – mostly acoustic, because acoustic was the kind of the anchor for this. If we couldn’t deliver acoustically, then it wasn’t a product, as far as we were concerned.”

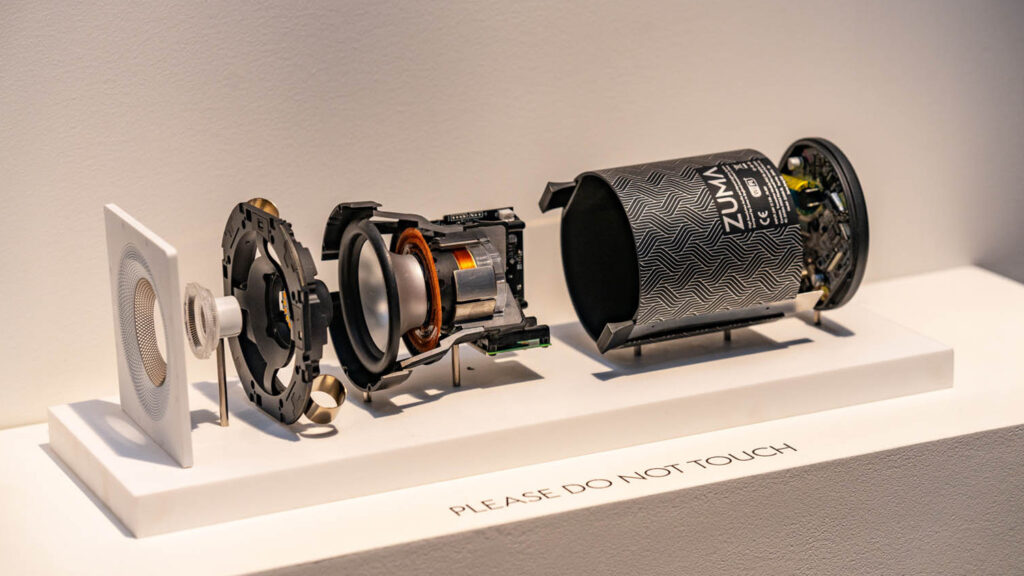

The first challenge was to deliver a full-range drive unit, with the team spending months attempting to combine different loudspeaker components.

“We never got what we wanted using off-the-shelf parts,” admits Rose. “And so, we just hit this wall. We realised we were going to have to do it from scratch, the whole thing.”

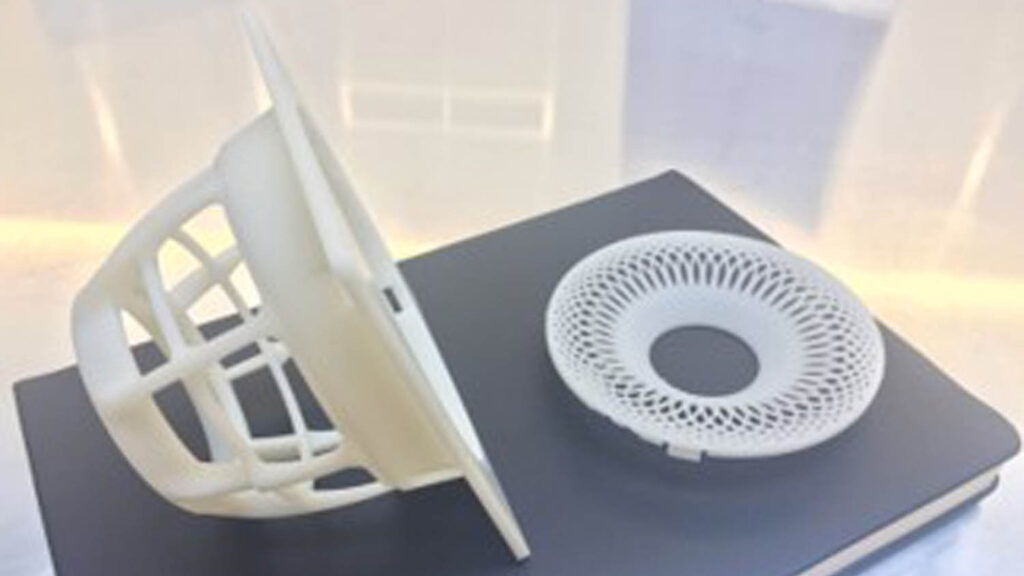

At Native’s workshop, the initial team of three began to develop parts and processes for the entire unit in Solidworks, before physically prototyping the devices.

Native has long invested in its physical prototyping ability, something its engineers cite as really changing their ability to not only to prototype quickly, but also in the real materials.

The team spent weeks forming 0.4mm anodised aluminium diaphragms, 3D printing the chassis on Formlabs desktop units and 5-axis machining steel motor surrounds. They also built custom magnets, customwound coils, hand-pressed rear suspensions and moulded polyurethane surrounds.

“We had hundreds of different designs; nothing was going to work… except we then had this one eureka moment, where we’d basically got the configuration right,” says a still-excited Rose.

“We’d got these arms. We’d got the LED in a ring that would fit around the tweeter at the centre. We’d got the horn to prevent the sound from getting out. We’d proved the shape of the drive unit was going to work.”

Over one Christmas, the first 20 or so Lumisonics were hand-built, and the team assembled them into a roof space where they could showcase the prototype system – in a set-up not unlike the Zuma retail showroom of today.

Turning on a Zuma speaker for the first time was a revelation, says Rose. “As soon as we heard it, we were like, ‘Okay, we’re off to the races!’ That was the unblocking point!”

Ready, steady, improve

From here the challenge only grew. The audio had to be improved, with the team employing specialists in simulation, along with world-renowned acoustic engineer Laurence Dickie, previously the chief acoustician at audio company Bowers & Wilkins.

On top of this came the task of making the speaker manufacturable. Zuma chose an audio manufacturer because of all the smart speaker elements, but the team had no idea about lighting or the kinds of complex thermals the Lumisonic would have to handle.

It took persistence to overcome these problems, says Rose. With the speaker packed into the space, the LEDs had to be integrated with the aluminium casing and heat sinks, helping suck every bit of heat out the LEDs to maintain their lifespan.

Custom-designed elements had to be refined, such as the doughnut shaped lens, and antennas to connect the WiFi, as well as the super-responsive, sub-100 microsecond RF connectivity (there are 1,000 microseconds to a millisecond), which links all the units in the system.

The antennas had to be capacitively coupled to the aluminium chassis to achieve optimum performance while encased in metal.

The light surrounds that sit on the inside of the room vary from inconspicuous to eye-catching. Native’s previous work for Bowers & Wilkins’ in-car audio brand meant the team had experience in designing audio-friendly speaker grilles and patterns.

The final part of the development was the integration of sensors into these surrounds and a look to the future expansion of the platform beyond light and sound.

With a computer already onboard, the team included a tiny connector on the front face of the unit, which acts as a USB. “What that means is we can now plug in cameras, sensors and all sorts of other things onto a bezel that will snap on to the front of your unit after you’ve installed it and expand the capability to do whatever you might imagine,” explains Rose.

Clutter be gone

Zuma’s design enables it to remove clutter from the connected home and pack it into a discreet light fitting. A surround with a microphone can be clipped onto one of the units, while another can be fitted with a camera, creating a baby monitor or part of a wider home security system.

With each Lumisonic unit containing the full array of technology – capable of acting as the main WiFi receiver and transmitting to the network – the cost is not cheap.

However, the Zuma team has thought this through with its unique fitting mechanism. Traditionally, light fittings have butterfly springs that lock them into the ceiling cavity, Rose explains. “You force them up through the plasterboard, and they munch great holes out of it, and you can’t get them out again without pulling them harder than you want to.”

Building a butterfly mechanism pivot into the tightly packed casing of the design would have eaten up another 20% of the space in a design already 100% smaller than the designers wanted it to be.

“We were really restricted by the amount of air volume we had here. How well your loudspeaker can perform is directly related to how much air volume you can give it,” says Rose, producing a thin slip of metal with a short black plastic handle. “We came up with a concept for using these constant-force springs, which would allow us to trap the unit in the ceiling.”

The slip of metal acts as a retainer for two springs on the sides of the new unit when taking it out of the box and fitting it. Once wired up and in the hole, the installer simply has to pull the handle on each retainer and, behind the plasterboard, the unrestricted springs coil to hold it in place. Replacing the retainer slip into each side of the unit pushes back the spring, allowing the unit to be removed.

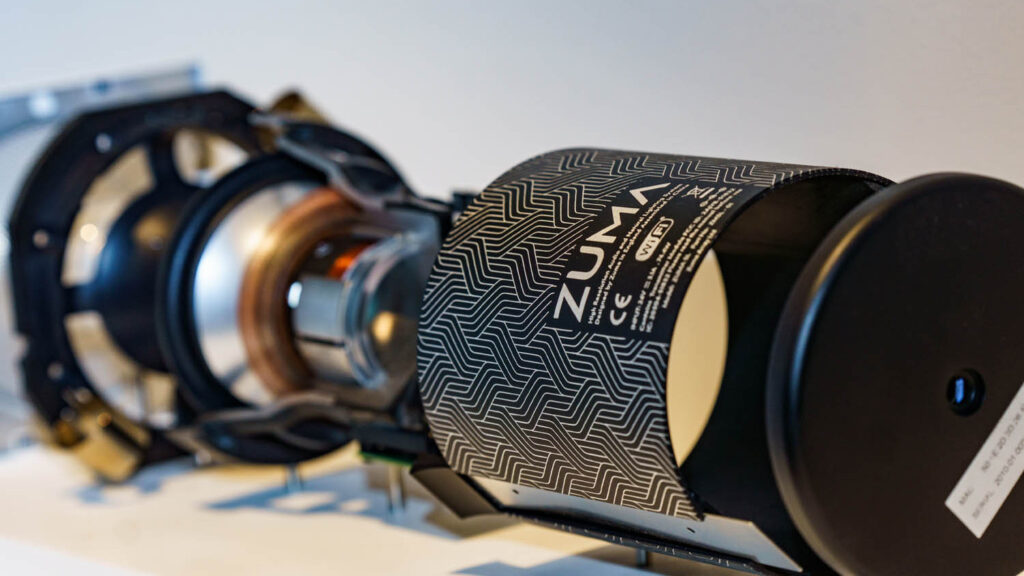

Everywhere you look with this product, attention to detail stands out. Even the casing that’s soon to be locked away in the ceiling is black-anodised and laser-etched to reveal a geometric pattern and Zuma branding. It has been designed not as a Bluetooth-connected consumable, but as a benchmark for the next evolution of connected devices.

The design tackles so many engineering challenges that, until now, no other company has successfully achieved what Zuma has. Its success is as much down to how the project was funded – few audio companies would veer into lighting, and fewer still would do so in reverse.

“It was so development-intensive and so expensive. You certainly wouldn’t have got favourable terms from seed funding, because for a long time, it was not entirely clear that it was going to work out,” says Rose.

Backing from Native’s founder Morten Warren is what drove this. “He stayed absolutely committed,” says Rose. Proof, if proof were needed, that what makes for a successful product is often having the right connections.