Although it may look rather beautiful and serene from the outside, the Orb is crammed full of advanced technology, enabling it to perform a rather clever task.

The Orb, draws your attention with its interesting design details including its soft ring of light, sphere shape and laser etched flower pattern

Developed for use in beauty salons and spas, it’s essentially a continuous heat chamber that keeps skincare products such as oils, waxes and muds warm during a beauty treatment. Once removed from its base station, the technology within the product maintains its contents at a constantly warm temperature for up to one hour.

The Orb is the brainchild of husband and wife team Jane Scrivner and Kevin McWilliams. Having worked in the skincare and therapy industry for many years including running her own salon in Stratford-Upon-Avon, Scrivner spotted a definite gap in the market. “It came out of a very simple idea that a lot of beauty treatments are improved by applying warm products to the body. But the reality is that the way products are being warmed and kept warm is not very good or technically safe,” she explains.

Current methods involve placing a vessel containing the skincare product either inside a bowl of hot water, propping it on a radiator or placing it inside a hot towel cabinet. However, as soon as the vessel is picked up, the temperature of the product within immediately starts to cool down. The process of having to keep it warm becomes distracting for both the therapist and client.

So, the idea was to invent a way of keeping the product safely warm for the average treatment duration of one hour. Being an engineer with a background in heating technology, McWilliams had created a rough egg-shaped prototype out of polystyrene. Armed with this and their business plan, which was based around launching a series of novel appliances aimed at the beauty industry over a five-year period, the couple began looking for investment.

They managed to secure £120,000 from the University of Warwick Science Park’s Minerva Business Angel Network and Midven, the West Midland’s specialist venture capital company. Aside from funding, the network also introduced the pair to the Manufacturing Advisory Service (MAS) West Midlands, which provided further support through its New Product Development programme.

Helping hand

One area of support was to put them in touch with the Coventry-based product design consultancy Smallfry, which would be able to help turn their vision for the Orb (at the time they called it Facepot) into a manufacturable product. Although Scrivner was very clear that she wanted a beautiful, reliable, safe, continuous, practical and portable product, she didn’t quite know what it should look like.

Smallfry believes that in order to design successful products you must walk in your client’s shoes to help understand both the overt and latent needs of the target user. So, the Smallfry team went over to Scrivner’s salon to experience a treatment and appreciate firsthand the problems she was having both from a therapist’s and a client’s point of view. “It was quite pleasant actually having all these hot oils and muds applied to your skin,” laughs Steve May-Russell, Smallfry’s managing director.

It became obvious to the designers that, with no specific means to keep the skincare products warm, the therapist was frequently distracted. They all agreed that the experience was definitely made less relaxing because of it. “When on the table just in a towel, you are feeling pretty vulnerable and you want to be made to feel at ease. The last thing you want is someone who keeps nipping off all the

time to reheat the oils,” describes May-Russell.

Design DNA

Smallfry strongly believes that design can be used as a business tool for commercial success. In order to develop innovative and practical products that sell its team spends a long time with the client at the front end of the design process discussing the market context, the strategy, the brand and other opportunities.

In this case, Smallfry discussed with Scrivner and McWilliams, amongst other things, where the Orb could sit in the marketplace and what the brand objectives were. “So, in a way, at the very beginning you start to prescribe the DNA of this thing that you are going to build,” says May-Russell.

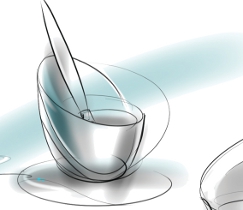

From here a range of concept sketches were created by Smallfry’s team on their Wacom tablets, led by creative consultant Daniel Bartram. These were then worked up in Photoshop and Illustrator and shown to Scrivner and McWilliams. “We call this the ‘Mr Potato Head’ phase. The client picks their favoured concept and the aspects of the other concepts they like and we amalgamate them to create something gorgeous that exceeds their expectations,” explains Bartram.

One of the features that Scrivner and McWilliams were particularly taken with was the wave around the product that helps to enhance its spherical shape. “I was able to add this distinct detail without overpowering the product’s initial purity and beauty,” says Bartram. “This in turn helped with practical challenges of how to keep component split lines to a minimum and also made it more ergonomic as the high sided areas provide a natural and intuitive way to hold the Orb.”

Another feature that they liked was the soft ring of light in the Orb’s base station, which illuminates whenever it is plugged in. “I created the ring of light as a bit of drama,” explains Bartram. “It also adds value to the product and overtly draws your attention to it.”

Turn up the heat

Having created an SLA prototype for aesthetic purposes, the next stage was to look at the heating technology.

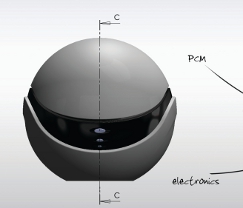

Although McWilliams had already sought a manufacturer of electric heating solutions – DBK Technitherm, based in Wales – the dilemma was not only heating the product but retaining that heat. Various ideas were discussed and debated between himself and the Smallfry team and the ‘eureka’ moment came when McWilliams thought of using phase change materials (PCM). “I had been doing some work on that for other projects in SPApliance’s stream of products. I realised that using the PCM together with a heater would give us a solution,” explains McWilliams.

Basically, a PCM is a substance with a high heat of fusion that is capable of storing and releasing large amounts of energy. In this case, as the material changes from a solid to a liquid and then back again, it absorbs a lot of heat during the process. “The best way to think of it is a special way of storing heat. It’s a heat store but it stores a lot more heat than a normal block of material of that size because it has a special phase change capability,” explains McWilliams.

Within the Orb, a disc of PCM (the heat store) is placed between the electric heater and removable product cup. When connected to the base station the electric heater is energised via spring-loaded probes and the heat store absorbs the heat and conducts it to the removable product cup to bring the contents within it to an ideal temperature of 70 to 80 degrees. Typically this takes less than 15 minutes.

During this process, as the heat store absorbs the heat, it changes from a solid into a liquid. When the therapist removes the Orb from the base station, the heat store starts to return to a solid state and in so doing releases its stored latent heat. During this phase change it will continue to conduct heat to the product cup and maintain that ideal temperature for up to an hour.

Meeting of minds

DBK and Smallyfry actually met before DBK started working on its heating element and Smallfry started refining the product. Smallfry always work closely with the manufacturer on its projects and in this instance both Smallfry and McWilliams felt the earlier the designer and manufacturer met in the process, the less problems would be caused further down the line.

“DBK came to our offices and we had a two hour head scratching session with a flip chart and scribbles,” says Bartram. “From there we worked closely with them on the technology and to ensure that the design intent was kept.”

In order to work out how the technology would all fit within the Orb, Bartram brought the design into SolidWorks, a tool he has been using for over 14 years and which he finds especially useful for technically challenging projects such as this. “The breakthrough was creating a core chassis moulding on the inside that all the components clip to,” describes Bartram.

These CAD models went back and forth between himself and DBK to ensure that all the technology could fit within the space. A number of prototypes were also created to prove the technology and were used by DBK to carry out various tests in its labs.

Up to the challenge

Bartram admits that this was a very challenging project. “Every design challenge that you can think of was chucked at it. The Orb not only had to be gorgeous, but also the ergonomics had to be considered and it had to be a comfortable temperature to hold despite all that heat inside,” says Bartram.

May-Russell adds, “The reason why I love this project is because the challenge was all technical. It’s got some belting technology inside but looks so serene outside.”

Certainly the biggest challenge was the colour selection, which according to May-Russell is always a very emotive subject with clients. Scrivner knew that she wanted two colours in the Orb range, one of which had to be white. “But I discovered that there is no such thing as the colour white. There are thousands of different shades of white from blue white to ivory white,” she comments. The other colour they eventually settled on was a dark chocolate brown.

Texture and finish was of course also very important. Although limited to plastics, they soon discovered from speaking to a plastics consultant and drawing inspiration from the car industry, that a great deal can actually be achieved in plastic. The Orb not only features a combination of matt and gloss finishes, it also has a flowery pattern laser etched onto the outside. “This was a very steep learning curve because we not only had to quickly find out what plastic to use but whether it would qualify for global plastics requirements,” says Scrivner.

In amongst all of this McWilliams and Scrivner also had to file for patents. They currently have four patents pending on different aspects of the product.

Final stages

Once the product was finalised, Smallfry sent the CAD files to DBK who then liaised with the toolmakers Mouldtech, which produced the tools and plastic parts at its subsidiary in Portugal. The assembly of the Orb then took place at DBK.

Following a few modifications after the first run, which was colourless and was done for proof of concept purposes, the second run consisted of a few hundred sets. These were used for the launch, which took place at two trade shows earlier this year.

So far interest has been very favourable and Scrivner is hard at work promoting the product and talking to distributors. Meantime, McWilliams confesses that he is keeping out of mischief by concentrating on SPApliance’s remaining product range.

www.spapliance.com

www.smallfry.com

The advanced technology held within the Orb is more than skin deep