Everybody remembers LEGO from their childhood. Hours on end would be spent snapping those little bricks together to construct post offices, fire stations, knight’s castles – even your own robots or mythical characters.

Since the company was founded over 50 years ago in Billund, Denmark, it has developed and marketed a wide range of products with thousands of different brick designs and colour combinations. In fact, over the years enough LEGO bricks have been manufactured to give each of the world’s six billion inhabitants an average of 62 LEGO bricks each.

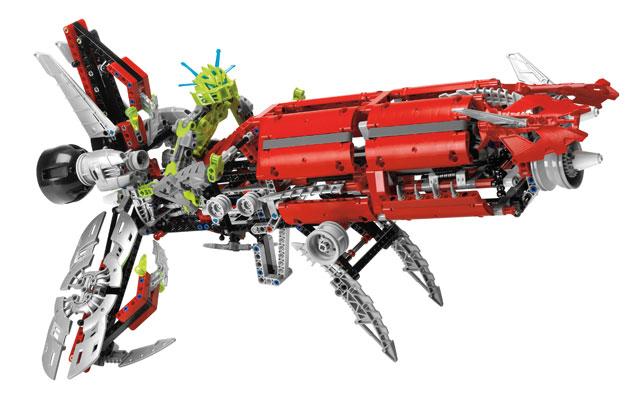

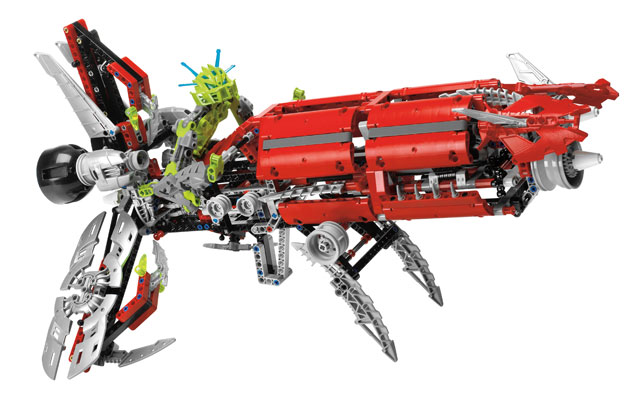

Lego’s Axalara T9 was launched this summer. It features 693 pieces in total, which means it has the most pieces of any Lego Bionicle creation to date

In recent years the company has faced tough competition from electronic toys and games, but the humble brick still continues to appeal to children despite the onslaught of products such as the Nintendo Wii and Roboraptor. “Electronic toys have revolutionised the toy industry but there is still a great demand for traditional toys,” explains Mike Ganderton, creative director of LEGO’s product group 3. “LEGO has embraced technology where it makes sense (for example Mindstorms and the LEGO Star Wars games) but mostly we compete by staying true to our brand and to our fans who love the LEGO product.

“We ensure we create products that will excite children by building strong and dynamic development teams that are impassioned to create world class LEGO products and campaigns.”

Adapting product development

Concept and product development takes place primarily at the Billund headquarters, which is home to 120 designers representing about 15 different nationalities. There are also other satellite offices in the UK, Munich, Barcelona and Tokyo, which either consist of small design teams developing ideas for local markets or are there to act as a monitor of trends. Ganderton, who has been working at LEGO for the past seven years, first as design manager and now as creative director, has overall responsibility for three lines – Bionicle, Racers and Technic. Each line consists of a small design team that works closely with marketers and project leaders as well as a design manager who reports to him. “In total there are 22 toy designers in my area and together we are responsible for the play quality and visual appeal of the products,” he explains.

LEGO’s product development process has undergone some significant changes in the past few years. “When I joined it took years from idea to production and each team did it their own way based on the experience of the individual team members,” comments Ganderton. “A few years ago we aligned the processes with the introduction of the ‘LEGO Development Process’. All projects now follow a standard process and our ‘idea to launch’ cycle is much quicker and more efficient.” The average period of development for a new product is now about 12 months.

The design process is divided into three main tasks: exploring, developing and validating. “All projects in LEGO tend to follow the same flow,” says Ganderton. “We first identify opportunities based on company business objectives, developments in the market or consumer trends. We next define project objectives and then set about the development task of exploring, developing and validating the design solutions.” According to Ganderton, dividing the design process into these tasks not only helps the teams be more effective as they can clearly see the objectives that need to be reached, but also more efficient as they can plan the appropriate resources, tasks and tools that will be needed. Additionally, it also helps to communicate the designs to colleagues within the company such as the marketing and management departments.

The consumer too plays a key role in all stages of the development process. “It may be the kids who play with the products, but it’s often the parents or grandparents that buy it, so some designers are stationed in toy shops at Christmas listening to and helping customers,” explains Ganderton. In the exploring stage of the design process the designers will either draw on research in the fields of play and learning or actually interact and interview children. “We bring kids into our process in very early development stages and watch them play in natural environments with our own products or with other toys. We also talk with them and ask what they want from new LEGO products and particularly with the Bionicle line, what kind of missions they would like to undertake,” he says. In the validating stage, children and parents are brought in again to test the designers’ models and concepts.

Toys for boys

The line that Ganderton has most enjoyed working on during his time at the company is Bionicle as it was the first LEGO project to get a story developed in-house. Introduced in 2001 the Bionicle universe is a science fantasy set in a world that is inhabited by biomechanical (part organic, part machine) beings and each year LEGO creates new story lines and introduces more characters.

“It was a real innovation in the toy industry and was a huge overnight success,” explains Ganderton. “LEGO built on that first wave of products with new designs and an ever evolving story to create a strong LEGO owned IP.

Designer working on the model of the Bionicle Axalara T9

“Today Bionicle is one of the best selling product lines, which is all the more impressive as we’ve done it without a TV show or theatrical movie release,” he adds.

The most recent product to be launched in the Bionicle range is the Axalara T9, a 19cm tall flying battlecraft with dual sky blasters and tri-arms featuring lasers and force field capacitors. “We had insights that boys would like vehicles for their Bionicle action figures,” says Ganderton. “We had already decided to do a flying theme for the overall Bionicle line so we defined and objectified to create a range of buildable flying vehicles in a Bionicle style.”

The designers kicked off the developing phase by creating mood boards to help identify the type of vehicles they would like to create. They then sketched ideas and in order to visualise and conceptualise these sketches they built models using LEGO elements or bricks. From here they moved into 3D and used Rhino to create new LEGO elements, which were then prototyped using an in-house SLA machine. “We created a number of special SLA elements from CAD files in order to create an aerodynamic look,” confirms Ganderton.

A range of different models were then presented to the entire project team as well as in focus groups with children. Final concepts were chosen and the feedback gathered from this validating phase was used to refine the design in order for it to not only appeal to the end user but to also meet cost targets. “Many iterations were created in order to optimise the building process,” says Ganderton. “It’s really important that the user has a good experience building the toy so we spend a lot of time and resource getting this right.”

The next step was to build the model virtually, which also allows the designers to create the step-by-step building instructions for the user manual explaining how to construct the Axalara T9. “From this virtual model we also create a Bill of Materials in order to be able to plan how to manufacture the elements and pack the final product,” adds Ganderton. The finished CAD model is also used extensively by the wider organisation; for instance, the communication department can use it to create the design for the packaging as well as other marketing materials.

Brick by brick

When the product is ready for mould manufacture the engineers model the elements in Unigraphics. Using this software tool they can optimise parts by conducting mould flow and stress analysis. “If we are uncertain about how a plastic part will perform we make a prototype mould to test it before committing to mass production. We make moulds with up to sixteen cavities so it’s important to get it right,” says Ganderton. As all Bionicle elements are moulded at the factory in Billund, the design team can very easily communicate with the production team and see the moulding process first hand.

However, as Ganderton points out, although having the factory onsite makes communication much easier, the real communication takes place in the project team itself with the designers, the part designers, the mould designers and the mould technicians all working very closely, quite often around the same desk or computer screen.

During the moulding process, Acrylonitrile Butadiene Styrene (ABS) plastic (the same material that has been used to create LEGO elements since 1963) is heated to 232°C until its consistency is about that of dough. It is then injected into the moulds at a pressure of 25 to 150 tonnes, depending on which element is being produced. It takes seven seconds to cool and eject new elements. Each injection mould is permitted a tolerance of no more than one thousandth of a millimetre, so that bricks of every colour and size stay firmly connected.

However, only the most specialised and skills-related LEGO elements are now manufactured in the Billund production facility because in recent years, in order to achieve planned cost savings, the company took the strategic decision to relocate from its existing production sites in the US, Denmark and Switzerland to facilities in Eastern Europe and Mexico. Although this transition period has been complicated, LEGO is adamant that its high quality level has been maintained. It had previously outsourced to several partners, including mainly the electronics manufacturing services company Flextronics, but an announcement was made during July that LEGO would now manage its own global manufacturing set up and take over production plants in Mexico and Hungary. Together with Billund the LEGO Group has its own production sites in the Czech Republic and cooperates with other manufacturing suppliers in Poland, Hungary and China.

A designer using Rhino to create the rider’s mask of the Axalara T9

Despite these relocation activities its annual report confirms that the company has been able to meet most of the demand for LEGO products and according to the company’s CEO Jorgen Vig Knudstorp this has only been possible through the impressive effort made by its employees. For one, Ganderton is a very loyal employee and motivated by the challenge of innovating and creating new products year on year. “Working at LEGO is great because I’m proud of the products we make and the values of the company. When I tell a stranger I work as a LEGO designer they usually get all excited and tell me about positive childhood experiences or the joy it brings to their kids,” he says. “It’s a very rewarding product to design since its purpose is to give kids enjoyment and allow them to express and develop their creativity.”

www.lego.com

The building blocks of design at LEGO

Default