Having spent the last month examining the current crop of desktop 3D printers, Al Dean has come to the conclusion that while great hardware is one thing, it’s the software that really makes these devices sing

Long-time readers of DEVELOP3D will know that I’ve always been cautiously optimistic about the potential for desktop 3D printing. I’ve seen these machines mature, progress and become truly useful in the last 10 or so years.

This month, I got to spend some close-up time with three new machines, each very different and each with its own strengths and weaknesses.

If I look at these machines as a group, what impresses me most is how much the build quality of the parts that come out of them has improved. We’re talking here about parts that are pretty cock-on in terms of dimensional accuracy.

It seems that the hardware manufacturers have finally worked out how to make accurate parts on the desktop after all. That, in turn, can only make such machines more useful to the product design and engineering professional.

After all, its one thing to knock out a model of a boat (read: the common ‘Benchy’ benchmark model). It’s quite another to build parts that match exactly the intent and that are sufficiently within tolerance to be useful and meaningful for design review, for engineering evaluation and yes, in some instances, end use.

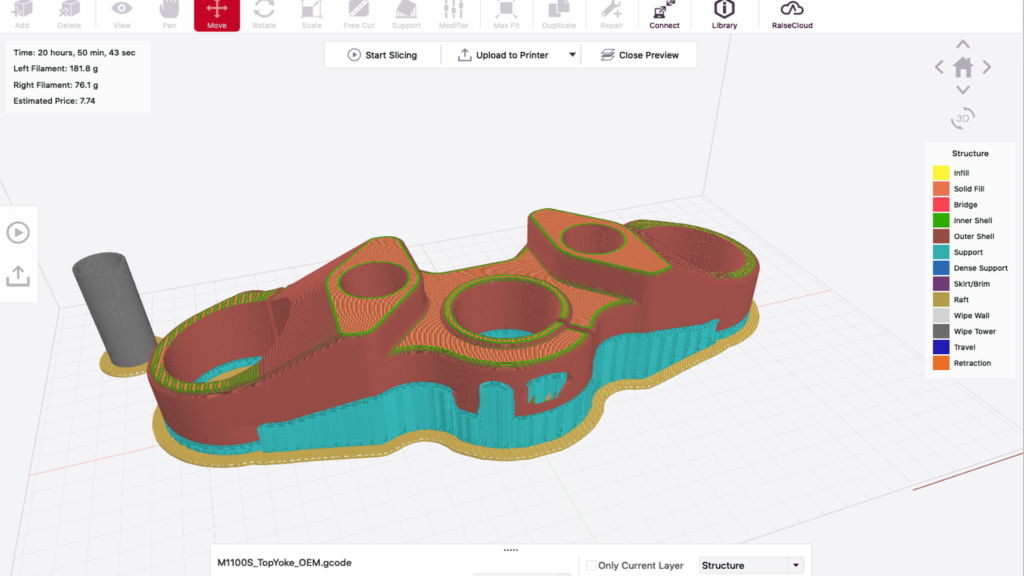

How have they achieved this? The answer lies in having a more precise view of what machines and materials are doing. Each machine is built to make the most of the materials it supports (with the exception of the Raise3D machine) and to control that material’s behaviour during builds. And much of that control comes down to one thing: software.

And just as with hardware, software tends to come with some great features that make perfect sense to you and others that drive you absolutely batshit crazy.

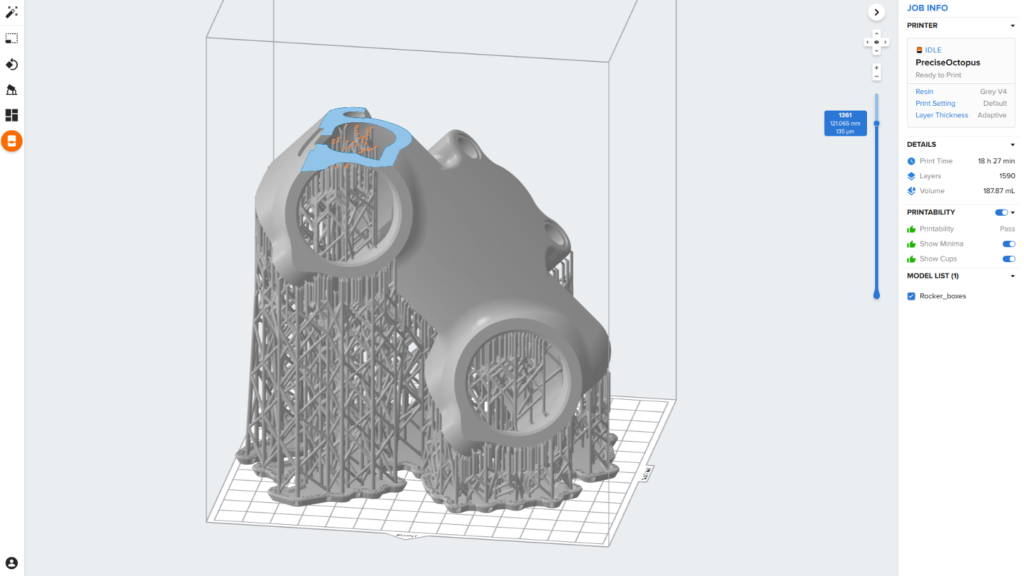

I’ll give you two examples. The first is Formlabs’ Dashboard service. This is cloudbased and, while it doesn’t yet contain the pre-processing you need to prepare a part for print in one of its machines, it helps monitor builds. It also tracks how you and your team use your machines, from what materials are used to the lifespan left in build tanks.

That is incredibly useful for those using such machines in a commercial environment, since it allows them to not only strip out costs for project costing, but also affords a quick look into future costs, which is great for setting realistic budgets.

Makerbot is working on a similar range of functions for its CloudPrint service. Other vendors are doing the same.

In fact, all across the full spectrum of additive, this is becoming a trend. Attention is turning to the process management aspects of additive, rather than pure cycling of parts out of a machine. The desktop is just a microcosm of that trend.

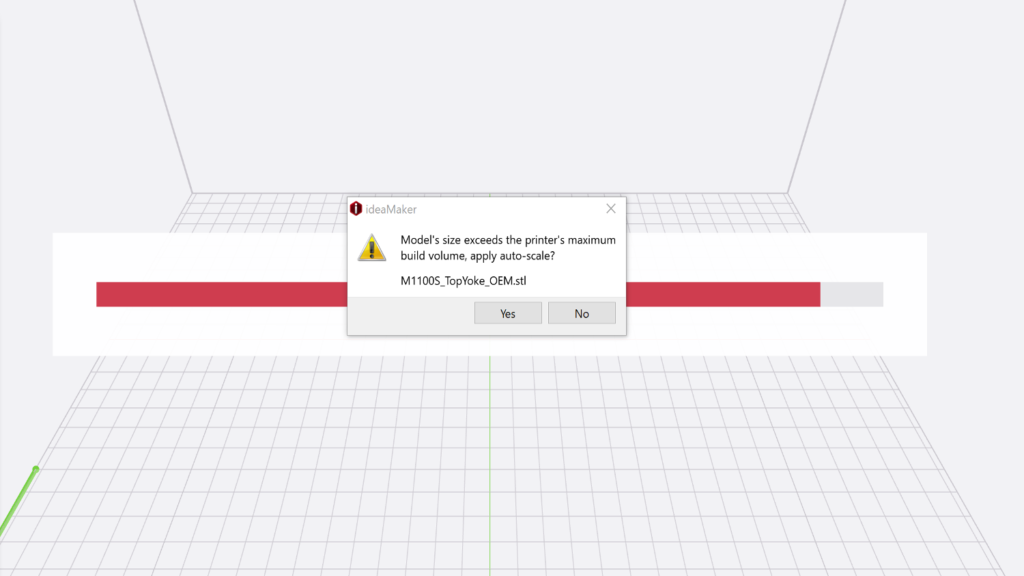

Then you get the infuriating things. One personal pet peeve is the dialogue that pops up when you import a part and it doesn’t quite fit the build volume of your machine. What would be the most sensible option for the software to offer here? Let’s think. It has the geometry, so it could quickly work out a bounding box. It could offer to rotate your part. It could offer to carry out some analysis to find a better fit.

But no. What we actually get is this: “Hi. Your part is too big. Do you want me to shrink it to an arbitrary percentage?”

It might be that 2020 is getting to me, but every time this pops up, I twitch and mutter under my breath: “No, I don’t. I don’t want you to scale the part. Just like I don’t want you to build me a Yoda head or a frigging tugboat. Find me a way to build this part in your known volume, using the materials available.” Is that really too much to ask?

The thing is, the machine never answers me. I inevitably end up clicking ‘No’ and then spend 10 minutes twiddling the part around to get it to fit, just as I knew it would all along.