We are certainly in the midst of a transformation in the way that 3D content creators and consumers interact with, exchange, and even make physical 3D data.

On his blog 3dsolver.com Tom Kurke wrote on how he felt that the next ‘napster’ era was upon us for digitally captured real world content

Traditional notions of what represents content worthy of protection will be stretched, perhaps even broken, as an acceptable solution is found for all participants in the ecosystem.

One that enables 3D content creators to properly monetise their creativity, whilst allowing 3D content consumers to leverage quality content, possibly even paying for it along the way. It won’t be easy, but there is a path forward.

In early 2012 I began a series of posts on my blog 3dsolver.com on the intersection of intellectual property (IP) with the dramatic changes influencing the 3D capture/modify/make ecosystem.

Of course, 3D printing is but one of many possible outcomes of a 3D capture and design process. In the first post in this series entitled The Storm Clouds on the Horizon in February 2012, I discussed my thoughts on how the “Napster” era was upon us for digitally captured real world content.

There is a growing awareness and understanding of IP considerations in the 3D ecosystem from consumers who wish to use their in-home 3D printers to produce an item to a company within a distributed digital manufacturing chain working for a large consumer goods company.

Concerns about IP have been accelerated by the transformative technical changes on both “ends” of this ecosystem.

The technological shift

Over the last few years there has been continuing acceleration in the hardware, software and services necessary to empower digital design and manufacturing processes.

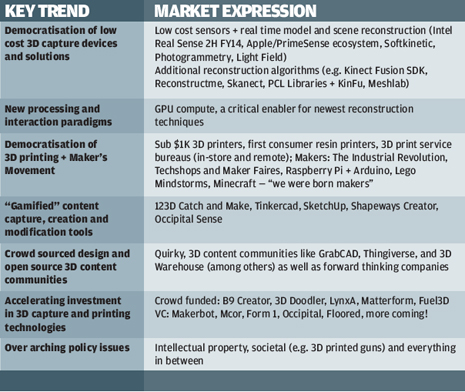

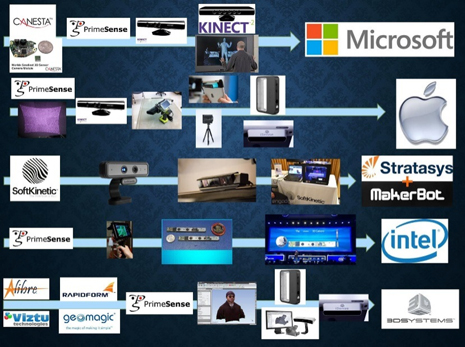

Earlier in 2014, I identified the following key trends in the capture/modify/make ecosystem for object based 3D capture and manufacture:

We are at a unique point in which both “ends” of the capture to make ecosystem are being impacted by dramatic technological changes. The change is continuing, the pace is accelerating.

Many new entrants in the 3D printing space

The last several years has seen many new market entrants on the consumer/prosumer 3D printing side. But, in my opinion, what is equally or more transformative is the impact that new low cost/smaller form factor 3D capture devices will have in this space.

For instance, Intel now adds its RealSense depth sense technology to every laptop it ships, Google is progressing with Project Tango along with its software partners, and other 3D data capture solutions are also being developed and distributed to consumers.

I looked at some of these market players in a blog post I wrote in November 2013 entitled Apple buys tech behind Microsoft Kinect (PrimeSense) – 3D Scanning Impact?.

Then in December 2013 I examined how new passive 3D capture technologies, leveraging plenoptic (a.k.a. light field) cameras, may find their way into consumers’ phones or tablets in Light field cameras for 3D imaging.

The recent research paper, which is co-authored by Microsoft Research and published during SIGGRAPH 2014 earlier in August, Learning to be a Depth Camera, demonstrates that 3D capture and interaction can be implemented by applying machine learning techniques and minor hardware modifications to existing single 2D camera systems. (More of this here on my blog)

With the convergence of technologies, it’s likely we will see the growth of multifunction 3D capture and printing devices that attempt to offer “one button” reproduction (and transmission/sharing) of certain sized objects in certain materials.

Examples even exist today. The ZEUS, for instance, is marketed as the first “ALL-IN-ONE 3D Printer / Copy Machine” whilst the Blacksmith Genesis recently started a crowd-funding campaign on Indiegogo.

While I believe the eco-system is lagging in producing software tools that make it easy for non-professional users to create, find and personalise 3D content, we are only a short time away from dramatic changes there too.

When people can more easily digitise, share, copy and reproduce real world 3D content – how will that change the landscape for content owners and consumers alike? What existing business models will be threatened and what new ones will be created?

What exactly “is” intellectual property in the context of digital manufacturing?

Many things! It may be represented in trade secrets – as in the confidential, differentiated manufacturing processes used to produce something. It may be represented by copyright – as in the rights a sculptor would have in his latest creation.

It may even be represented by patent – as in a unique and novel device. In the EU, a design can also be protected by registered or unregistered design rights With this in mind, what if your son broke the leg of his favourite action figure and you decided to repair it using something you produced and either printed on your own 3D printer, had it printed at Staples or had it printed and shipped from Shapeways?

What if you were able to find and download a manufacturable model (in STL format) of that action figure that someone had uploaded to one of the many model sharing sites and used that as the basis of the print job?

What if the person who uploaded the file had created the model by hand? What if the person who uploaded the file created the representation by 3D scanning an undamaged action figure? What if you scanned, printed, and repaired the item in your own home but did not share the files?

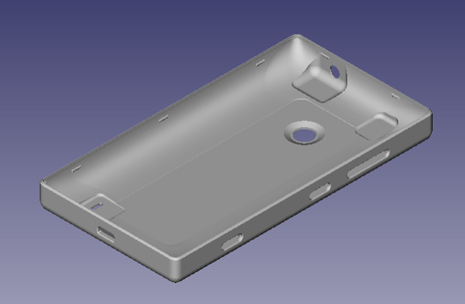

What if it was not an action figure, but a retaining ring (below) for one of the low voltage lights that keeps getting run over in your front garden? Do these differences matter? Absolutely.

The type of content (artistic or functional), the reason for manufacture (new item, replacement part, etc.), how the content was generated (from scratch, printable file obtained from a third party, the end result of a 3D reality capture process, from the manufacturer, etc.) and where the content will be manufactured (in your home, at a local store, on a third party’s networked printer, at a remote service bureau and shipped, etc.), all matter. In some instances the content might not be protected at all, in others it might touch multiple types of third party IP.

There is not enough space within this article to give you a general primer on all of the IP issues in the create/capture/modify/make ecosystem. Instead I have provided a list of several excellent publications and presentations as background reading (see box out below).

Authors in this space cover a broad spectrum of opinions – from those who believe that IP issues need to be better understood in digital manufacturing as many objects are generally not protectable, to those who believe that the democratisation of capture and printing technologies will utterly transform manufacturing supply chains and potentially substantially devalue IP rights.

I fall in the middle ground, believing that the fundamental technical and market changing technologies will stretch the concept of IP and, as we have seen with the music industry, over time the ecosystem will adapt – including the law.

Intellectual property concerns an impediment to continuing growth?

IP concerns have moved beyond theoretical to being deemed by manufacturers as one of the most potentially disruptive impacts of the broadening reach of additive manufacturing.

In June 2014, PricewaterhouseCoopers (PwC) and the Manufacturing Institute published the report 3D printing and the new shape of industrial manufacturing (PwC Report).

The report is broad reaching and well worth an extended read. One section in particular examines the potential for additive manufacturing to shrink supply chains. It reads: Companies are re-imagining supply chains: a world of networked printers where logistics may be more about delivering digital design files—from one continent to printer farms in another—than about containers, ships and cargo planes.

In fact, 70% of manufacturers we surveyed in the PwC Innovations Survey believe that, in the next three–fi ve years, 3DP will be used to produce obsolete parts; 57% believe it will be used for after-market parts.

When the PwC Report survey participants were asked to identify what they felt the most disruptive impact wide adoption of additive manufacturing technologies could have on US manufacturing, the ‘threat to intellectual property’ was second only to ‘supply chain restructuring’.

This concern should not really be all that surprising.

A graph from the PwC Report on the disruptive effects of 3D printing

In October 2013, the market research firm Gartner, in conjunction with its Gartner Symposium/ITxpo, made a series of predictions that would impact IT organisations and users for 2014 and beyond. Several related to the impact that cheaper 3D capture and printing devices would have for the creation of physical goods – predicting staggering losses from the piracy of IP.

A press release published by Gartner states: By 2018, 3D printing will result in the loss of at least $100 billion per year in IP globally. Near Term Flag: At least one major western manufacturer will claim to have had IP stolen for a mainstream product by thieves using 3D printers who will likely reside in those same western markets rather than in Asia by 2015.

The plummeting costs of 3D printers, scanners and 3D modelling technology, combined with improving capabilities, makes the technology for IP theft more accessible to would-be criminals. Importantly, 3D printers do not have to produce a finished good in order to enable IP theft.

The ability to make a wax mould from a scanned object, for instance, can enable the thief to produce large quantities of items that exactly replicate the original.

I do not share the dire predictions of Gartner. Firstly, many of these hardware and software technologies have existed for many years and secondly, the process of creating high quality digital reproductions (either from “scratch” or from a 3D reality capture process) is still very difficult, even for experienced users. But over time, if a consumer can manufacture something in their home at comparable cost and quality to what they’d buy in a store, why wouldn’t they?

Intellectual property in digital manufacturing

Obviously there must be a willingness of content owners to share and distribute their IP for distributed manufacturing, whether as part of a collapsing supply chain for industrial manufacturers or to authorise someone to produce a licensed good in their own home.

We are seeing companies test the water. For instance, Nokia experimented in early 2013 by providing STL and STEP models of certain phone cases for 3D printing, in early 2014 Honda released its 3D “design archives”, and recently Hasbro licensed a handful of artists to create derivative works based on a toy from its My Little Pony line.

Nokia Lumia 520 Shell, author: Nokia (CC BY-NC-SA 3.0)

These customisations can be purchased from Shapeways. Buoyed by the success of this launch, Hasboro and Shapeways are now soliciting designers to create customised 3D printable designs based on Dragonvale, Dungeons & Dragons, Monopoly, My Little Pony, Scrabble (to be sold in the US and Canada only) and Transformers – with upload instructions posted to superfanart.com.

What will accelerate these types of projects piloted by Nokia, Hasboro and Shapeways?

There are obviously business and technical hurdles in distributed digital manufacturing, but there are also some fundamental IP issues which need to be resolved as well: I’ll examine each of these issues and potential resolutions in more detail below.

In my mind, there are clear parallels to the music industry – what lessons can be learned from the digitisation and distribution of digital content there? Which business methods are ultimately prevailing?

Manufacturing file format encapsulating intellectual property information

The de-facto standard for digital manufacturing is STL (from STereoLithography a.k.a. Standard Tessellation Language). STL benefits from being well known and is computationally easy to read and process, but the challenges with it are many.

For instance, it doesn’t scale well to higher resolutions, there is no native support for colour or materials properties, it’s unit-less and doesn’t compress well.

A new standard has been proposed to replace STL, known as AMF (Advanced Manufacturing Format a.k.a. STL2). Al Dean reviewed AMF and compared it to STL in his January 2013 DEVELOP3D article Alpha-Mike-Foxtrot to STL.

More useful background information can be found at the AMF Wikispace.

Without getting into a debate as to whether the current AMF specification is “good enough” to grow into the next de-facto standard, it is important to recognise that the handling of IP rights are specifically excluded. Section 1.4 of the ASTM AFM specification reads:

This standard also does not purport to address any copyright and intellectual property concerns, if any, associated with its use. It is the responsibility of the user of this standard to meet any intellectual property regulations on the use of information encoded in this file format.

Further, the AMF specification is lacking support for metadata containers that would allow for the file content to be self-describing at some level.

What is needed? A file format (AMF or other) for manufacturing that specifically allows for metadata containers to be encapsulated in the file itself. These data containers can hold information about the content of the file such that, to a large extent, ownership and license rights could be self-describing.

An example of this is the ID3 metadata tagging system for MP3 files. Of course the presence of tag information alone is not intended to prevent piracy, but it certainly makes it easier for content creators and consumers alike to organise and categorise content, obtain and track license rights, etc.

Inconsistent/inappropriate licensing schemes for 3D data

Most 3D printing service bureaux and model hosting sites have licensing terms that are only concerned with copyright, rather than dealing more broadly with the entire “bucket” of potential IP ownership and licensing concerns.

Several rely on the Creative Commons Licensing (CCL) scheme, or some variation thereof, as the foundation for the licensing relationship between their content creators/contributors, content consumers/users and their own services.

Being concerned only with copyright, or exclusively using the CCL scheme for manufacturable 3D content (via 3D printing or otherwise), is misguided.

Creative Commons is acutely aware of using the wrong license type for functional content, see the blog post on its website from January 2012 entitled CC and 3D Printing Community.

The challenge with the current CCL schemes are that they were never intended to cover “functional” content, that which might be covered by IP rights other than copyright. According to the above blog post: With the exception of CC0, the Creative Commons licenses are only for granting permissions to use non-software works.

The worlds of software and engineering have additional concerns outside of the scope of what is addressed by the CC licenses. 3D printing is a new medium which encompasses both the creative domains of culture and engineering, and often 3D printed works do not fall neatly into either category.

Creative Commons explored the creative/functional split in a Wiki for the 4.0 release of licenses, but did not develop a framework for a license covering both types of content.

I examined these issues previously in more detail in a two part post on my blog at the end of last year The Call for a Harmonized “Community License” for 3D Content. While dated, these materials can be useful background.

Why does this matter? There is presently no licensing consistency among the various players in the digital manufacturing ecosystem – potentially meaning that there are tens, or even hundreds, of “flavours” of license grant, for the same content.

What is Needed? An integrated, harmonised licensing scheme addressing all of the IP rights impacted in the digital manufacturing ecosystem – drafted in a way that non-lawyers can read and clearly understand. This is no small project, but needs to be done.

Do the “Safe Harbor” provisions apply?

It is possible, via secondary or vicarious liability, to be held legally responsible for IP infringement even if you did not directly commit acts of infringement.

In 1998 the Digital Millennium Copyright Act (DMCA) became law in the United States. The DMCA creates limitations on the liability of online service providers for copyright infringement by third parties when engaging in certain types of activities – primarily relating to the transmission, storage and searching/indexing of data. These have become known as the “safe harbour” provisions of the DMCA.

To receive these protections, service providers must comply with the conditions in the Act, including providing clear “notice and takedown” procedures that permit the owners of a licensed content to stop access to content which they allege to be infringing.

The DMCA provides a “safe harbour” to service providers for copyright infringement. If, for example, it turns out that they hosted or store content upload by a third party which was found to be infringing. There are a few key limitations: (1) the content may not be modified by a service provider (if it is, the DMCA safe harbour protections do not apply); and (2) the DMCA only limits liability for copyright infringement, it does not help protect a service provider from other potential forms of infringement.

Wick Harbour, user: Dorcas Sinclair (CC-BY-SA-2.0)

The first DMCA “take down” notice for 3D printed content was sent to Thingiverse (now part of Stratasys) in February 2011 for a Penrose Triangle that could be 3D printed. Shapeways, Materialise and many others in the ecosystem on the notice and what it meant for the industry at large.

Unfortunately, in a world of distributed digital manufacturing, there is the potential for more than just copyright infringement – functional items that are manufactured and used may (and I stress may) violate third party patents, trademarks, trade dress, design rights, etc.

This could open up participants in the digital manufacturing chain to claims of secondary infringement for rights other than copyright. These are typically much more difficult claims to make, just by the nature of what needs to be demonstrated under the law, but potentially chilling nevertheless.

What is Needed? Extension of the concepts in the DMCA to cover the broader bucket of IP rights beyond copyright.

In Section III(c) of Patents Meet Napster: 3D Printing and the Digitization of Things (see box piece below) a similar conclusion is reached and a framework for implementation is proposed. Such changes need to be considered and implemented in a way that does not create or extend secondary liability to more players in the ecosystem, but rather provides a safe harbour for certain non-copyright claims should infringement liability otherwise exist.

More certainty will bring business model exploration

Forward thinking content owners, like Hasbro, recognise that over the next several years there will be substantial transformations in the digital manufacturing ecosystem.

IP metadata in self-describing digital files, harmonised licensing schemes and revised statutory frameworks will help accelerate these changes.

Ultimately, there is a universal market need for an IP licensing, clearance and payment infrastructure to support the seamless distribution and payment for manufactuable content.

When content creators have an easy way to monetise their content through licensing, content consumers can find and pay for quality content, and simple personalisation tools have been created, we will truly see a transformation in digital manufacturing.

Further reading

A few excellent publications and presentations as background to intellectual property issues in the create/capture/modify/make ecosystem, principally looking at US law, however:

● ‘Patents Meet Napster: 3D Printing and the Digitization of Things’ tinyurl.com/digiofthings. This is a good review of all forms of IP in the ecosystem, as well as proposed changes to existing statutory framework.

● ‘It Will Be Awesome If They Don’t Screw It Up: 3D Printing, Intellectual Property, and the Fight Over the Next Great Disruptive Technology’ tinyurl.com/dontscrewitup. A seminal article written by Michael Weinberg at the Washington DC-based public interest group Public Knowledge.

● ‘3D Printing and the Future (or Demise) of Intellectual Property’ tinyurl.com/demiseofIP. Presentation by John Hornick, a partner at the US IP law firm Finnegan.

● ‘What’s The Deal With Copyright and 3D Printing’ tinyurl.com/dealcopyright. Followup article by Michael Weinberg, does a good job of explaining the important nuances in an IP analysis involving physical items versus digital representations of those models.

● ‘Legal Aspects of 3D Printing’ tinyurl.com/legalaspects3D. Whilst the other articles and publications deal with in depth issues, this article on the European Parliamentary Service website provides a useful broad summary of the various issues.

Tom Kurke tackles the subject of IP in the world of distributed digital manufacturing

Default