Hill Helicopters is on a mission to bring a heightened sense of excitement to the business of luxury transport, by combining the glamour of the hypercar with the unparalleled convenience of vertical take-off. Claudia Schergna meets the brand propelling a new era of rotorcraft

Owning a helicopter is like having your own magic carpet. There’s no need to worry about traffic, road closures, red lights or runways. It’s travel at its most luxuriously expedient.

However, the personal helicopter industry has suffered in recent years from a lack of the new blood needed to bring competition and innovation to any sector.

The team at Hill Helicopters intends to change that. The company’s launch product, the HX50, is dubbed a “flying supercar” by founder Jason Hill and is due to launch at the end of 2023. The aim is to position the brand on the cutting edge in both design and engineering, updating helicopter standards to rival the exclusivity and luxury seen in top automotive marques.

The story begins when Jason Hill first spotted a gap in the market for a helicopter designed specifically for the modern private owner. These customers are some of the richest people on earth and they expect the very best, he reasons – but few manufacturers directly address their needs and expectations.

“We have a lack of competition, because it’s a stagnant industry,” he says. “The price point has become completely disconnected from what’s economically viable. [Other companies] have got to the point where they’re doing less for more,” he says.

“They are trying to piggyback a supply chain broken up into lots of different tiers, and trying to make a living and run an aerospace-qualified business off selling 20 [products] a year. Obviously, it’s got to be expensive.”

What allows Hill to market his company’s products at a more competitive price is no secret, he says: “What we’ve done is to cut all that nonsense out,” he explains. “By vertically integrating, we’re going back to how we used to make aircraft in the early days of aviation, where the company makes the whole aircraft. We make everything.”

This approach, he reasons, will enable the brand to sell the HX50 at roughly half the price of the nearest five-seat helicopter on the market. But when buying a helicopter, retail price is just the tip of the iceberg.

Additional costs come from three main areas, Hill explains. First, there’s depreciation; helicopters have a relatively short number of hours that they can fly before components need to be replaced and only a number of years before they need a major overhaul. Second, there’s the aforementioned lack of competition, which means the handful of companies that produce parts have a virtual monopoly. Third, there’s the cost of insurance, which is directly proportional to how expensive the asset is.

“We have to find a way to sort those problems out for general aviation,” says Hill. The key is to make it possible for more people to be able to acquire a helicopter, either personally or as a small group or syndicate – way beyond the 12,000 people per year who currently learn to fly them.

Another difficult aspect of designing and launching a new aircraft is dealing with regulations. Besides the challenges that come with meeting laws in the country where the aircraft is produced, there are international regulations to meet as well. These can prove tricky to negotiate, says Hill, because the stagnancy seen around design and engineering is also seen in the approaches taken by regulatory bodies.

Proof points

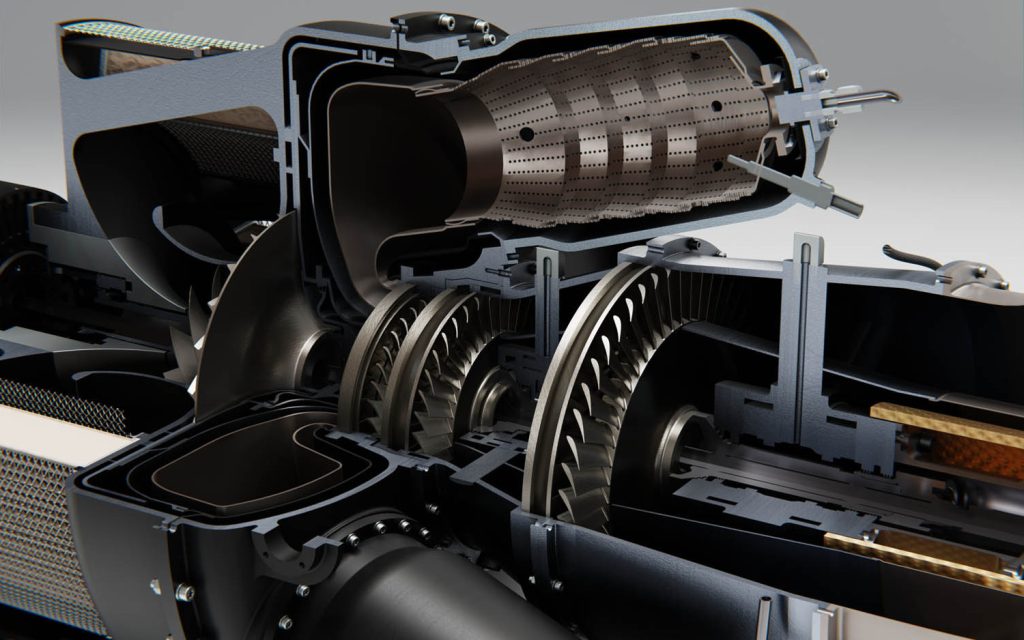

After working on early design schemes, engineering layouts, and looking into ways to upgrade traditional aircraft engines by using automotive derivatives – including types of diesels, two-stroke and four-stroke engines – Hill came to the conclusion that the technology he was after simply did not exist yet.

Faced with this problem, he and a small team of engineers began preliminary work to prove that they could build a brand-new engine, a project that rapidly moved on to designing the entire aircraft. With their initial 3D CAD design showcasing the project, they were able to secure a £1.4m grant from Innovate UK to begin further development of the private-use HX50 and its commercial-use variant, the KC50.

The difference between the models is minimal – simply a different approach to achieving airworthiness approval, Hill explains. Because of this, the launch date for the KC50 will be further off in the future. “It’s the same aircraft. We’ll just subject it to lengthy bureaucracy,” says Hill. “The HX model is purely focused on a streamlined path through regulations, much like it used to be in the old days, before the bureaucracy reached these dizzy heights that they’re at today.”

This involves using experimental or amateur-build regulations, he continues, “where we can bring the owners to the factory and get them involved in building their own helicopters as part of the ownership experience.”

The experience of being involved with the design and build of the helicopter is what attracts most customers, in fact. “One of the interesting questions [that comes up when] dealing with these kinds of people is: ‘What on earth do you buy for people who have already got everything in the world?’ And the answer is these kinds of once-in-a-lifetime experiences that money can’t buy.”

How much future owners can expect to personalise their rotorcraft? Around 51%, says Hill. Through the Hill Helicopters app, they are connected directly with the development facility, can receive live updates, leave feedback and ask the developers questions directly.

“It’s generating such a groundswell of excitement,” says Hill. “It means that you’re properly communicating with all your customers about exactly where you are, exactly what you’re doing and exactly how it’s going.”

The app will grow to include all the information one could possibly need about the management of an individual aircraft, with a portal for accessing safety and maintenance instructions.

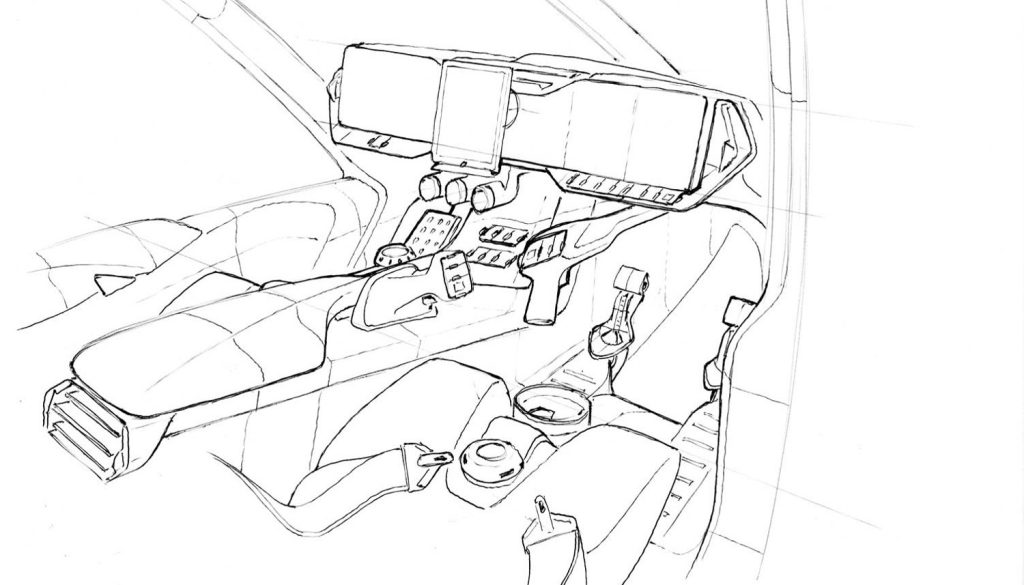

It also features a digital cockpit, where customers can choose from a wide range of options, from exterior paint colour to interior leather choices, personalising their helicopter before they visit the factory and have a chance to work side-by-side with engineers and technicians.

Renders are also produced in-house using Blender, to create marketing materials that generate initial interest, as well as bespoke work to aid customer buy-in. “We use renders to allow us to validate the as-designed appearance of the general vehicle aesthetics, fits and finishes,”

Hill explains. It’s a way to ensure that the quality of the aircraft matches the expectations of customers and the broader market before the design is finalised and the company commits to tooling.

Besides being key for visualisation purposes while an aircraft is still in development, Hill foresees that rendering will be a key tool for the commercialisation of the aircraft, as it’s easier and more convenient to generate stills and videos with modern rendering tools than traditional photography, even when the helicopter is finished.

Modern approaches to tradition

In contrast to the innovation seen in its design, the team at Hill began the development of the HX50 with the most traditional method: “Our design process starts on a white board, or on a piece of paper, or the back of an envelope,” he says. “We ideate, get the big picture and get all the bits in the right place. And then the next stage is to move into 3D and start concepting things. And then very quickly, we’ll bring in simulation.”

To accommodate designers from different backgrounds and education, the team uses a mixture of software tools. But overall, the process relies heavily on the company’s backbone of PTC Creo for 3D CAD and Windchill for PLM, supplied by its CAD technology supplier Concurrent Engineering.

The team runs initial simulations using methods including FEA and CFD to get an idea of the physical attributes of the concept, heat transfer, vibration characteristics, fluid dynamic issues and aerodynamics.

Calculations are carried out using PTC Mathcad Prime, to make sure as much empirically derived data is used as possible. Analysis is performed using the Ansys suite. The team then moves on to more comprehensive analysis to simulate rotor aerodynamics, structural dynamics, flight dynamics, flight mechanics and control systems.

“We’ve got the full suite of tools that you would imagine you would need to be able to develop an aircraft to the greatest extent possible in the virtual world before you build stuff,” says Hill. “

And then once you’ve done as much as you can, the next trick is knowing when to stop. You’ve got to know when to break the pencils and take people’s keyboards off them!”

Digital designs then move into physical prototyping, using HyperMill to programme the parts for in-house machining. The CAM phase is just as important as simulation, says Hill: “The thing that people need to be reminded of is that you learn so much by making things.”

Early versions of the concept are produced, to make sure the design meets all the requirements and is fully compliant with what the manufacturing process can deliver. “Otherwise, you have to start that whole journey after you think you’ve finished.”

Being vertically integrated is an enormous advantage, says Hill, as it allows more efficient communication between departments: “The guys that are designing stuff sit next to the guys that make stuff, and they sit next to the guys that run the machines. People can see that they’re not an island. They can’t just do what they want, and then chuck it over the fence, and have somebody else worry about it.”

Building a strong, reliable company is just as important as making an innovative, effective helicopter, he adds: “We’re developing the processes that make the helicopter. Not just the helicopter.”

Hill Helicopters // The journey to zero emissions

Even though they are powered by standard helicopter jet fuel, Hill claims its helicopters are the most efficient way to take off vertically. The modern rotor systems, both for the main and tail rotors, are both more efficient and quieter than existing systems.

This power system is complemented by the lowest drag coefficient of any helicopter in its size class. “We’re around a third of some similar size helicopters, because of the quality of the aerodynamic design. So our power consumption for a flight, particularly at higher speeds, is incredibly low,” he says.

While he agrees traditional fuels are not sustainable in the long term, Hill’s actively on the hunt for ways to reduce the carbon footprint realistically in the short term.

As he explains, “There’s no point in pretending that you’re going to be able to make a battery-powered helicopter anytime soon. It’s just not possible! A lot of the configurations that the top companies are looking at have worse energy efficiency than our helicopter.”

Biofuels are the immediate solution, he reckons. Electrifying the helicopters will make them even better, but a way to electrify them without using batteries – which creates a lot of other environmental issues like unsustainable mining efforts and the difficulty of disposal – is yet to be found.

“In the short term, the way to get to 95% carbon neutrality is to use appropriately sourced biofuels and sustainable aviation fuels,” he says. His own in-house developed engine, he points out, is designed to run on different sources of fuel, and these include biofuels.

“This is how we’re going to solve the technical challenges we face to make aviation more environmentally responsible in the short term,” he says.

“I’m not claiming that this is the answer for 30 years’ time. This is the answer for now. And it buys us time to solve the bigger problems with where we get all those electrons from.”

This vision sits with what Hill calls a ‘second wave of general aviation’, a movement for which he wants to be a leader, helping save the industry from further neglect, bringing the aviation sector up to speed with modern automotive standards, and getting people interested in flying again.

This wave is about fulfilling the desires of flying amateurs with models like the HX50, providing people with the magic carpet they’ve always dreamed of owning.