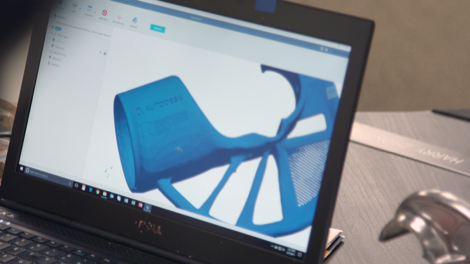

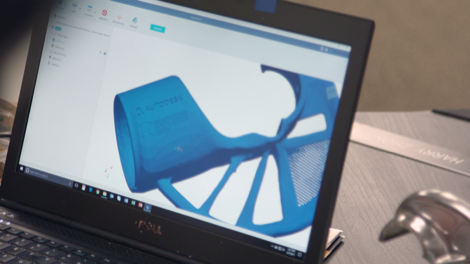

Stanley Black & Decker’s newly-formed Breakthrough Innovation group has been running a pilot program for generative design with NetFabb

Autodesk has announced that its generative design technology will make its appearance as a commercially available product inside of its Additive Manufacturing (AM) suite, NetFabb. For some years now, Autodesk has been showing off its set of generative design tools at various trade shows and user conferences.

While details have been scant, the company has made great stock of several public facing projects (with Airbus and others) that showed the potential for machine learning and artificial intelligence (A.I.) in the design world. What hasn’t quite so clear was how the company intended to bring it to market and turn it from technology into a tool that can be used by a wider audience.

Those that follow Autodesk’s work will be aware that the tools have been linked to Fusion 360, to a research project called Dreamcatcher and a few other instances and while much has been demonstrated, actual news on where this technology would appear, as a commercial entity, have been few and far between.

That changes this month with the news that Autodesk is looking to first make its generative design tools available inside NetFabb. For those that aren’t aware, NetFabb was acquired from its Bavarian parent company (FIT AG) a couple of years ago. The software tools are probably best known for its, now defunct, NetFabb free version, which allowed basic STL file repair.

The reality is that Netfabb product range is much more.

Alongside file preparation, the higher-level packages and modules give the advanced additive manufacturing specialist tools to prepare data, not just in terms of fixing part files, but much more – from build and platform chamber stacking and optimisation tools, to lattice design, metal process simulation, near net shape design and much more.

The news released today says that generative design will become part of the NetFabb suite (presumably in the high-end, NetFabb Ultimate, bundle) suite later this year.

But what is Generative Design?

While there’s a lot of talk around generative design at present, there’s little in the way of a de facto definition. McNeel were perhaps the first to adopt the term in the 3D design world, with the combination of Grasshopper and Rhino.

Siemens, more recently, have started to use the term in the promotion of its Solid Edge and NX capabilities.

For some it’s about using scripting to generate forms that would be hard to model using traditional means (which is where Grasshopper has seen rapid adoption in the architectural panel design space, for instance), for some it’s about topology optimisation (Siemens et al).

So in this instance, it’s worth including Autodesk’s definition verbatim:

“Generative design technology takes goals set by a designer or engineer, e.g. size, weight, strength, style, materials, cost, and any number of other criteria, and then uses cloud computing to create a massive number of design solutions.

“Using intelligent algorithms based on machine learning and advanced simulation, it produces smart design solutions that can be difficult for today’s designers and engineers to discover and model efficiently.

The designer or engineer then identifies and adapts the right solution as desired. This process leads to major reductions in cost, development time, material consumption and product weight and gives our manufacturing customers the ability to design and engineer in brand new ways.“

What’s fundamental to understand here is that generative design in the context of Autodesk’s thoughts and products isn’t simply about topology optimisation – something that is often confused with generative design.

While topology optimisation allows you to take a set of boundary conditions (or in more sophisticated tools, multiples of) and optimise the topology of a design space to best suite those conditions, Autodesk sees generative design as something over and above this.

It’s about using the compute power and intelligent algorithms to give you multiple solutions (we’re talking 100s of, not just one or two) to a range of design scenarios, loading and performance requirements and other influencing factors – not purely related to shape and force/constraint, but much more, such as shape, function, material, manufacturing process and such.

Part of the reason for the confusion and, if I’m honest, co-opting, of the term is that the end results are often visually similar. If they look similar, then they must be the same thing, right? No. Not at all.

So why NetFabb?

What’s not exactly clear right now is whether this is the extent of where this technology is going to end up. NetFabb makes huge sense for the first release. NetFabb’s commercial users are already inside the additive manufacturing world and are placed to take advantage of it most immediately.

After all, it’s no good generating these ultra-optimized forms if you don’t have the means to manufacture them.

There’s also the fact that if you’re using such forms in the world of metal part production, you’re going to need to be able to handle post build machining and finishing – something that the NetFabb tools, alongside the tools like PowerMill (also in the same product group) is built to do.

But where else will this end up? After all, Autodesk has, for the last two years, been making a great deal of noise about how generative design will appear inside Fusion 360.

Will that come in the near future? Only last year, there was talk of this technology appearing in the next 12 months or so.

Generative design, in the context of Autodesk’s definition and apparent toolset, is consistently aimed at the additive manufacturing world, but there’s huge potential for this sort of A.I. driven design tool outside of the AM world.

Imagine if you could apply the same thinking to structural steel work in the construction world, in the design of framework for machine tools or automation equipment, or a tubular framework for a car chassis? While the NetFabb integration makes sense as a first public offering, I’d hate to see it stay there and not be integrated into other tools in the Autodesk portfolio – there’s simply too much potential there.

In use at Stanley Black and Decker

The resulting generative designed part reduced the attachment weight by just over 3lbs, or 60%.

Stanley Black & Decker’s newly-formed Breakthrough Innovation group started with a Generative Design pilot project to improve a hydraulic crimper (meaning lighter). A conventional crimper weighs 15.4lbs and is used hundreds of times in a work shift.

Frank DeSantis, Vice President of the Breakthrough Innovation group, worked with our consulting team to define the desired criteria and insert it into the Autodesk Generative Design service.

After examining thousands of combinations of materials and processes, the service generated many options from which the innovation engineers were able to decide on a path forward, satisfied that they had explored all of the options – not just the three or four or even 10 options that engineers may have considered if they used traditional design tools.

The resulting generative designed part reduced the attachment weight by just over 3lbs, or 60 per cent. The simulations that were run concurrently showed that the tool maintained the strength characteristics of the original tool and, because the generative design service is available for Netfabb users, it also allowed them to create an additive manufacturing strategy to fabricate the new attachment.

“The generative design capabilities we can access with Netfabb are almost magical. It’s not brute force engineering. It’s elegant. You define a problem and you get a solution set unlike anything you’d predict.

The results of the wire crimper project ensure we’re going to be applying the incredible combination of generative design and additive manufacturing that Netfabb offers to an array of other products we have in development. This is clearly the future and that’s what our Breakthrough Innovation group is all about.”