The time has come for smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) in simulation, an approach that offers quick and simple options for fluids analysis in ways that could boost product development cycles, writes Laurence Marks

At the turn of the last century, the direction that simulation was taking was obvious. In the future, in addition to wearing silver suits and travelling by personal hovercraft (developments that felt well overdue to me at that point), every simulation would consider more than one physical domain.

No strength assessment of a bracket would be complete without a planet-heating consideration of how the surrounding airflow had been altered and how this in turn changed how we viewed the strength of the bracket. In short, the train labelled ‘multiphysics’ was about to leave the station and all the cool analysis kids were on board already.

In fairness to the simulation industry, lots of the things we were exploring and promoting became technically realistic for even the humblest analyst.

In many scenarios, multiphysics simulations have unlocked huge engineering benefits for lots of operations. But it’s just not the way in which all models are made these days.

It was at around this time that I first encountered smoothed-particle hydrodynamics (SPH) technology. While today, multiphysics might be seen as a a solution looking for a problem, SPH may well be an idea whose time has come.

SPH was first used in the late 1970s to model the way in which galaxies interacted with each other. It remained pretty niche for a while, almost certainly because, at that point, what we’d now think of as ‘traditional’ simulation techniques were hardly anything in technology readiness terms.

But by the 1990s, SPH codes were appearing inside mainstream impact codes, such as Abaqus Explicit and LS/Dyna.

It took me a while to find out why they were there, but it turned out that the principal motivation was modelling how a heron is transformed from a bird to bird soup in an aviation impact event.

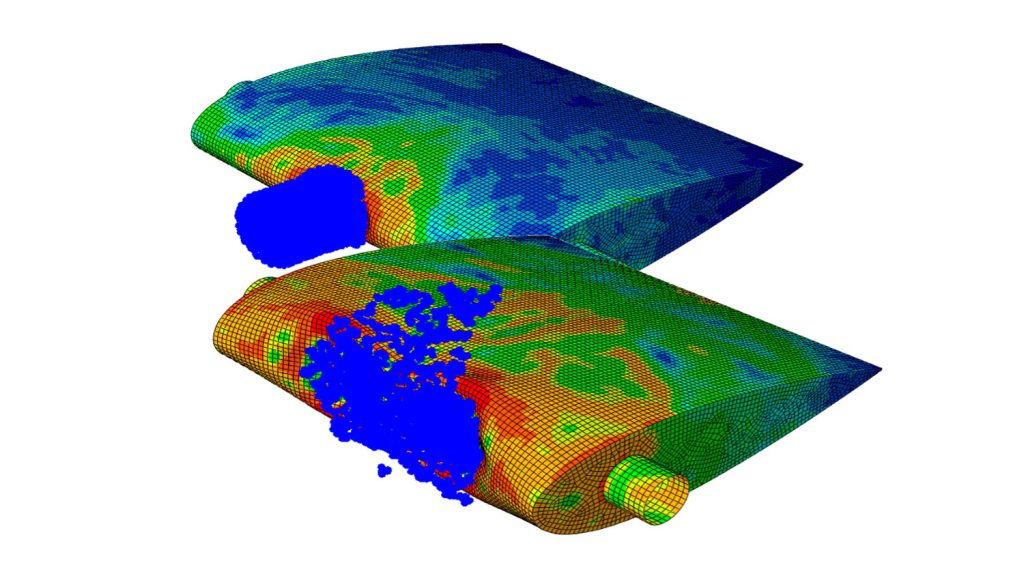

Actually, the focus isn’t on the bird side of the energy balance. The motivation was to model how aerostructures handle the impact of birds. SPH offered a great way to model the impact that a phase-changing avian has on an aero engine – but SPH is about so much more than bird strike.

Calculation points

Before looking at how the future seems to be unfolding for SPH, it’s probably worth a quick detour into how it works. It has been remarked by some industry figures that SPH isn’t particles, isn’t smooth and isn’t hydrodynamics.

While this is amusing, it’s also a useful insight into what’s going on. They really aren’t particles, because modelling particles is something else, it’s discrete element modelling, or DEM.

In SPH, the particles are calculation points. Rather than using a mesh like an FEA or CFD code, something called an ‘influence function’ handles the physics representing how the material behaves at and between the calculation points.

Being meshfree unshackles the solution to handle the sort of deformations we see in waves crashing onto a beach in a storm. As a bonus, it couples well with other simulation approaches and physics. And the way in which this solution works happens to perform really well on the current generation of GPUs, meaning you don’t need a supercomputer these days in order to run a model.

To add some balance, SPH is still a niche technology and won’t be eroding the turnover of traditional CFD companies in plenty of application areas, especially those in which the issue of turbulence rears its ugly and baffling head.

If you are lucky enough to join the current generation of cool analysis kids at a conference, what you’ll see are lots of new operations offering SPH-based flow products.

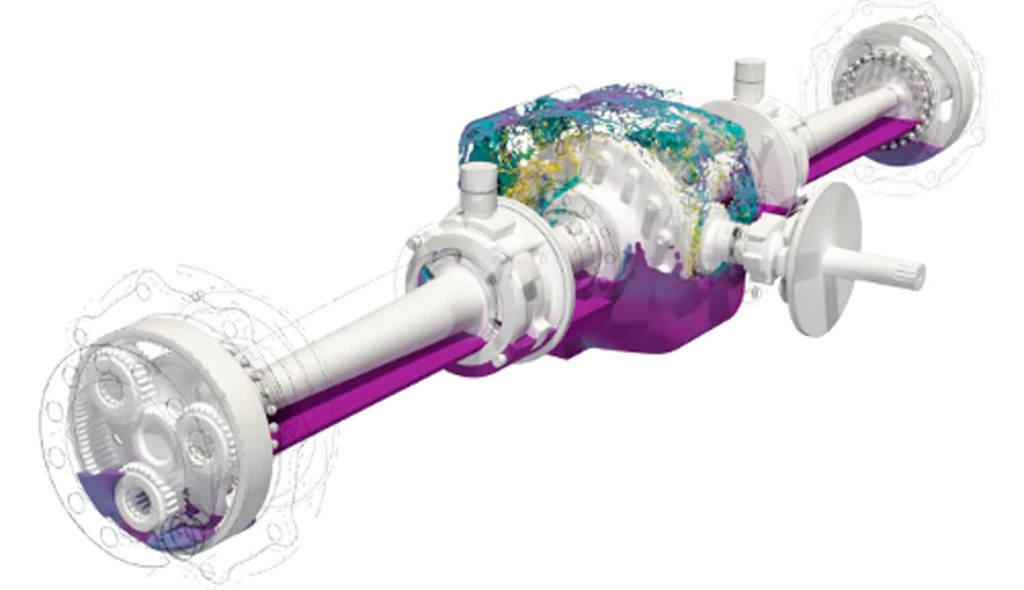

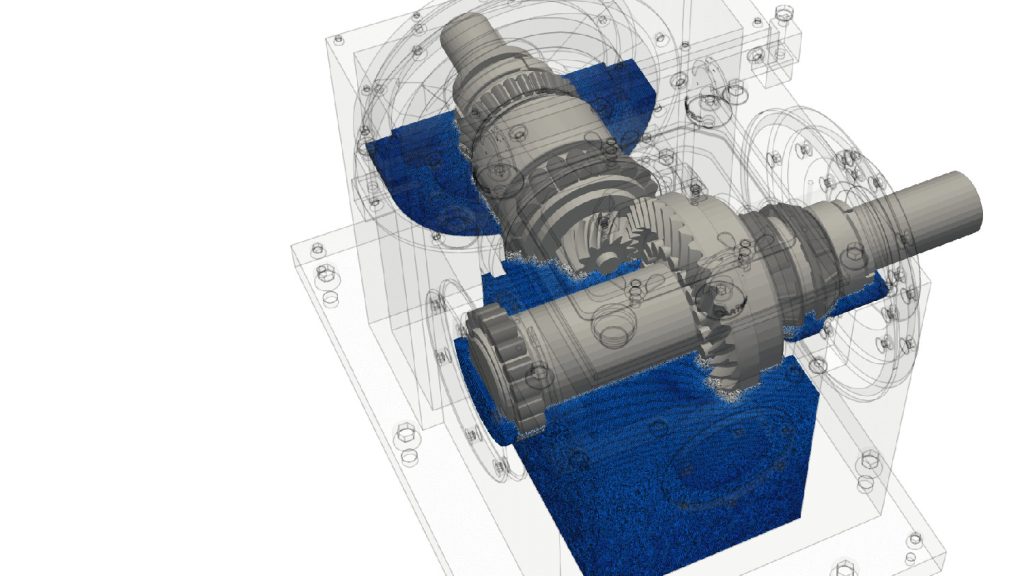

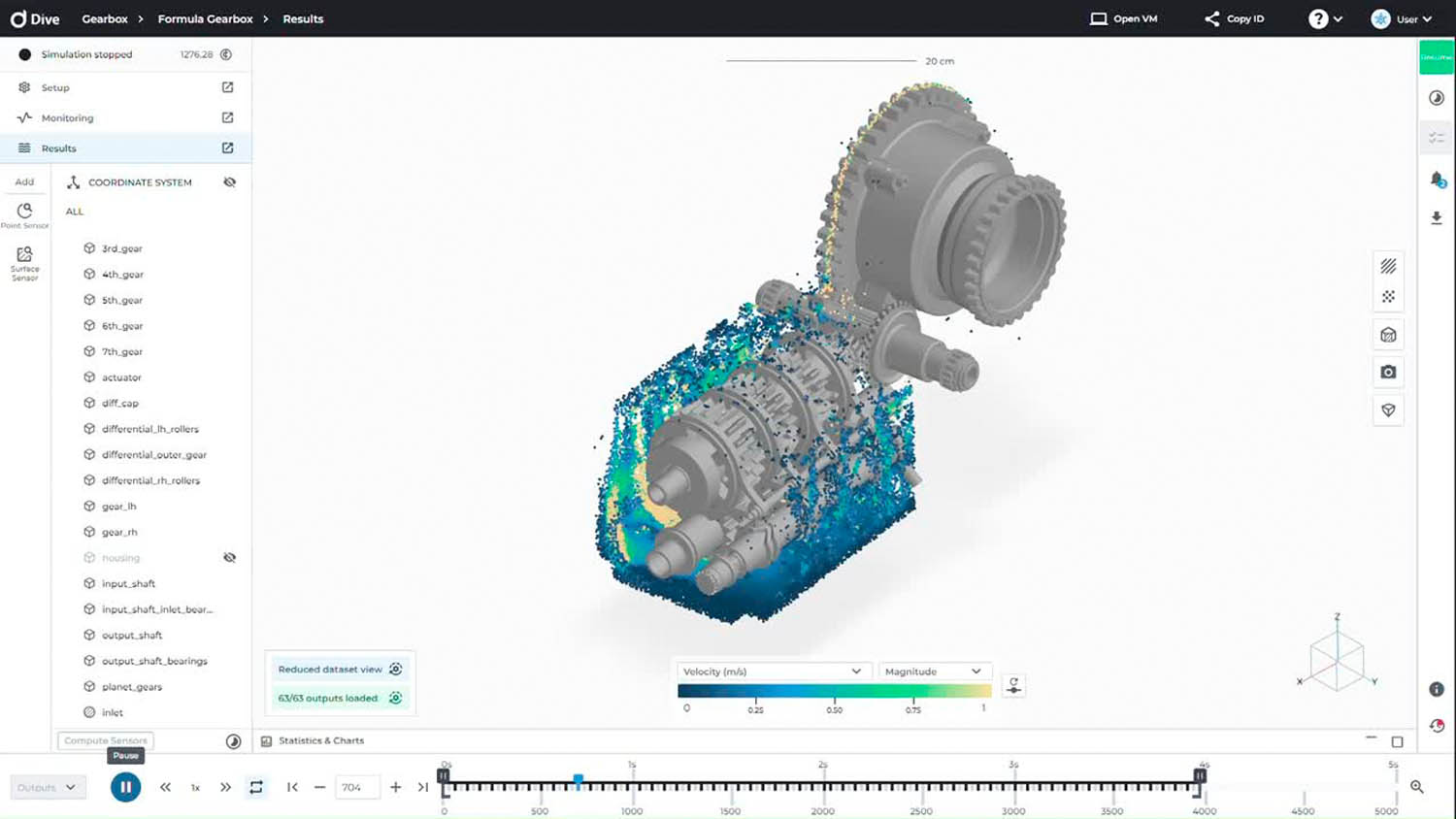

Because SPH provides an easy-to-set-up, rapid solution to complex problems involving fl uid and moving surfaces – like gearboxes – these products have gained commercial traction and are changing the look of the CFD market. In turn, they’re moving the focus away from the CAE megacorps who currently dominate the simulation landscape.

One organisation doing some super-interesting things in the SPH space is DiveCAE, a company that is headquartered in Berlin, Germany. As its CTO Johannes Gutekunst explained to me, Dive is pioneering a cloud-native engineering platform powered by its SPH engine, which can enable engineers to simulate complex material behaviour without meshing.

“We’re now expanding into structural simulation with our in-house FEM technology, creating a true multiphysics solution that combines CFD, structures and phenomena like conjugate heat transfer or porous media, all seamlessly in the browser.”

For those not ready to dive into a full SPH-powered package, DualSPHysics is an SPH code available for free download. It even has a decent(ish) FreeCAD GUI that sets it apart from lots of academic codes, in that you can actually use it. It’s what I’ve been testing recently. It runs very reliably on an Nvidia A4000 GPU and is worth considering if you’re looking to get into the game.

So maybe new simulation products based on SPH signal a new world order, one in which the ability to simulate and gain insights into a physical response can subsequently be used to drive product development, and where this is seen as more important than CAD integration. We can but hope.

www.laurencemarks.co.uk