Most product and industrial design students spend their final year at university concentrating on the design, prototyping and testing of one major project. But once they graduate and feel the pressure of finding a job in the real world, this project is soon forgotten.

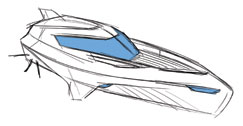

Asap – an electric power assisted water craft for beach lifeguards

In response, Loughborough University has set up The Studio to help recent graduates kick start and hopefully commercialise these product ideas by offering them office space, access to the University’s resources, mentoring and financial investment based on a royalty agreement. One such graduate who has benefitted is Ross Kemp.

“After graduating in Summer 2011 The Studio offered to support my project by helping me set up as a start-up business. They also gave me a little bit of seed funding to develop the idea further,” says Kemp. “If it wasn’t for that support I probably would have, like most others on my course, put the project in the cupboard, the prototype in the garage and forgotten all about it.”

His product is Asap, an electric motorised watercraft with a market both in the lifesaving and leisure industries.

For beach life guards, the advantage of Asap over fuel hungry and expensive jet skis is that it’s easier to launch and only requires one person to both operate and perform the rescue at sea. Alternatively, it can be used as a miniature jet ski for personal leisure and sporting activities.

Life saving inspiration

The inspiration for Asap came about whilst Kemp was training as a lifeguard at Loughborough University, which he took up to strengthen his muscles after having broken his leg when hit by a car.

During his training he came to realise how difficult it was to tow a body, conscious or unconscious. He also discovered that a lot of the equipment lifeguards use – such as jet skis and paddle boards – is not only expensive but also rather outdated.

“It was from that lifeguard training that I started developing my alternative to a jet ski, which would be cheaper, more sustainable, faster and easier to operate helping to conserve the lifeguard’s energy for the actual rescue,” explains Kemp.

From sketching his ideas, he progressed to creating a CAD model in Pro/Engineer and then building a fibre glass prototype by hand in a tent in his back garden. He consulted with the Royal National Lifeboat Institution (RNLI) about his prototype and even took it to Skegness beach where he tested it in the sea himself.

Although Kemp was keen to make Asap a commercial reality he decided to get a ‘proper job’ as a junior designer in the Birmingham-based design office of Vax, a British floorcare brand. However, he still continued to work on Asap on weekends, evenings and during his one hour train journey to and from work each day.

“For about six months after graduation I didn’t do very much on the project as I was concentrating on my job at Vax, which I love,” he confesses. “Then one day The Studio sent me an email about applying for a new TV programme called ‘Be Your Own Boss’. I applied but didn’t think much of it until I got a call saying I was on the shortlist.”

Best of British Talent

The BBC Three series ‘Be Your Own Boss’ saw entrepreneur Richard Reed, co-founder of British drinks brand Innocent Smoothies, invest £1 million in young British entrepreneurs.

It started with Reed meeting 500 hopefuls in a warehouse in London who all had 60 seconds to pitch their business idea to him. In the subsequent six episodes he then invested a portion of that £1 million in those he deemed worthy.

For that first round, Kemp packed up his prototype and presentation boards and headed down to London in the hope of impressing Reed with his invention. His was one of the few product designs amongst many drinks, confectionery, branding and service ideas.

“There was a real buzz in the air as we all waited for Reed to come round to our stands,” remembers Kemp. “Then when he did, there were three cameras in your face as you pitched your idea. It was so scary but he seemed to like the product.”

And he did, as Kemp was invited back to Innocent’s head office in London, otherwise known as Fruit Towers, a short while later where Reed revealed that he was one of the 18 who had made it through to the next round.

He was given a seed investment of £3,000 and was told he had just six weeks to produce a prototype and business plan before he had to come back to pitch for a stake in the £1 million. If that wasn’t pressure enough, he would also have a film crew following him around.

No time to lose

But what about his day job at Vax? “I walked into the director’s office at Vax and told him the whole story right from the start. I confessed that I had no idea where this thing was going but could I have six weeks off starting from tomorrow,” reveals Kemp.

“I wondered whether he was going to fire me on the spot but luckily he said it was a once in a lifetime opportunity and to take it.”

With only the director and his manager aware of what he was doing, for confidentially reasons, Kemp disappeared to The Studio at Loughborough University where he would spend a very intense six weeks.

“There was an initial panic when I realised that I had just six weeks and not six months to design, prototype and test the design!”

So with no time to lose he spent the first two weeks creating a completely new version of his watercraft with help from his former tutors and mentor. The Studio also helped him find a company who’d be willing to produce a prototype in just three weeks.

“We had a meeting with the National Composites Centre (NCC) in Bristol who said it was possible to produce the top and bottom shells in that time frame. I was so pleased to have their help,” says Kemp.

The day before he was due to send his CAD files to the NCC, he met with a marine engineer at Loughborough University who was going to look over his designs. However, the meeting didn’t quite go to plan. “He asked why I’d put the motor at the front and not at the back.

Although I told him that it fits in better with the design, he said the reason the motor of any watercraft is always at the back is because that is where the pivot point is for turning. Something suddenly clicked and I knew I had to have the motor at the back,” comments Kemp.

“I then stayed up all night completely redesigning the whole thing before sending the files to the NCC by 9am the next day. I literally had to start from scratch. But the good thing is that when you’ve done it once, it’s a bit faster the second time. But it was still a very long night.”

Material gains

The NCC then went about machining the moulds for the top and bottom shell from a resin material with its in-house five-axis CNC cutter, which were then laid with carbon fibre. “I originally wanted to make it out of fibre glass as it’s cheap and more suited to the product.

However, the NCC had some spare carbon fibre and asked whether they could use it as it would be going out of date soon. That was amazing because it’s such an expensive material,” says Kemp.

“So making it out of carbon fibre meant it was incredibly light but also very thin with the whole shell of the watercraft measuring only 2mm thick. Although not realistic for manufacture it was great for a prototype and TV purposes.”

In parallel, Kemp was working on the electronics and creating the prototypes for the smaller components, such as the sprung loaded throttle, using Loughborough’s in-house prototyping machines. He also bought a better motor than that in his first prototype.

“For my final year project I bought the cheapest motor I could with my student budget. But with the seed investment from Richard Reed I could get a more powerful motor which I was delighted about because it meant the watercraft would go faster in the water,” he comments.

If that wasn’t enough, he also had to squeeze in some time to write his first ever business plan together with details of where Asap would be marketed and who would distribute it.

Following an initial set back from the RNLI, which said it could not support a ‘leisure craft’, he had a very successful call with David Bamber, chairman of seven lifeguard stations in South Africa, who was interested in being Asap’s first distributor.

“David Bamber found the product online whilst desperately searching for innovation in lifeguarding products. This was after a tragedy on a South African beach in March 2012 where 20 rugby players were swept to sea and unfortunately six drowned,” says Kemp.

Lights, camera, action

During the six weeks, Kemp also had the added pressure of the film crew and Reed breathing down his neck checking on his progress.

About half way through these six weeks he received a call and was told to come down to a meeting in London the next day. He had no idea what it was about and, after having sat in a coffee shop for hours, he was eventually called into a room where he met Reed and his guest – Sir Richard Branson. Kemp couldn’t quite believe it as this wasn’t just any meeting as Branson was there to listen and advise on his product!

One question he posed to Branson was that, although he knew there could be a big international market for his product both as a lifesaving craft and as a leisure product, how could he reach that market from the start?

Branson then offered to fly Kemp and his prototype to Bondi Beach in Australia so that he could test it with lifeguards there and hand out flyers to those on the beach. His reasoning was that, if Australians endorsed it on the famous Bondi Beach, it would be a far easier sell in the UK and other countries.

“Meeting Richard Branson and him offering to help me launch my business was the highlight of those six weeks. It was really the motivation I needed to encourage me to keep going and made all those all-nighters and hours sat in front of the computer worthwhile,” says Kemp.

But from that high he hit the ground with a bump as D-Day was fast approaching. “If it wasn’t for people like the NCC helping me with the prototype then I probably would have just had a bag of bits at the end of the six weeks rather than a fully working craft that we managed to test as well.”

“The final pitch was at Fruit Towers at the end of July 2012. Unfortunately I didn’t get the investment from Reed as he thought it wasn’t the right investment for him and a field he didn’t know enough about. It was gutting but so much good has come from the TV programme,” says Kemp.

Since ‘Be Your Own Boss’ was broadcast last September, not only has his story been featured in local papers and radio shows, he has been asked to present at his old school as well as Loughborough University.

“It’s strange to talk to students having only graduated so recently but I think one of the reasons Loughborough asked me to do it is to prove that you can be both – an entrepreneur working on a product idea as well as maintaining a day job,” he says.

Kemp has also received emails and calls from people offering to help or invest in his business.

“The most amazing thing from the TV show has been that all these contacts and investors have come to me, which is incredible. Normally you’d have to go searching and banging on people’s doors,” he comments.

It’s been a roller coaster journey for Kemp but his Asap watercraft is almost ready for manufacture. He had better chase Richard Branson up on that Bondi Beach offer then.

https://youtube.com/watch?v=fbstbY1Ax9Q%3Flist%3DPLFAB0EE2DCB7BAE40

asapwatercrafts.com

nccuk.com

lboro.ac.uk/thestudio

Pedal power

Two young automotive engineers from Bentley will soon be pedalling 3,000 miles across the Atlantic in a Torpedalo they’ve designed, engineered and constructed themselves.

The project started in October 2009 with the ultimate goal of breaking the world record and in the process raising £250,000 for their two elected charities — the MND Association and Make-A-Wish Foundation UK.

“Most people don’t believe me when I tell them that no beer was involved in the creation of Project Torpedalo,” says Mike Sayer, technical assistant to MoB, Engineering, Bentley.

“The idea to design, build and use an ocean-crossing carbon fibre pedal-boat, from scratch, to raise money for charity was one that grew from an amalgamation of several concepts between my friend and colleague Mark Byass and I in September 2009 — not, as most people expect, from an over-ambitious session in The Dog & Duck.”

With no budget to design, test, build and equip the boat, the project luckily attracted some high profile sponsors who have all had a part to play in bringing the craft to life including Autodesk, Curvature Group, John Burn and Norco Group.

“The support has been unbelievable,” says Byass, design engineer, Bentley. “To get this far on the kindness of our sponsors in supplying materials, time, products, and in some cases all three; without spending a penny of the donations we’ve received for the charities, really is unbelievable.”

Byass led the design of the Torpedalo, which is a closed-cockpit, triple compartment self-righting pedal-driven monohull. Having consulted with various marine industry experts, he set about creating a digital model of the boat.

“I used the same CAD tools that we use at Bentley; Alias, Inventor and Showcase,” says Byass. “They’re all really great tools, but when you use them all together you start to see huge benefits. Nothing can touch Alias in my opinion for surface modelling.”

Many months and revisions later, the hull was ready for testing at Newcastle University’s MAST towing tank facility. CFD was also used to optimise the aerodynamic profile of the upper surfaces resulting in a hull shape that can move relatively fast through the water and handles waves well.

“My favourite feature is the hull shape, it’s so simple but was a huge success in the model tests,” says Byass.

“It’s a century old design, optimised with Alias and realised with CNC’ed SikaBlock polyurethane foam donated by John Burn, which also supplied all the tooling board to make the boat mould tools.”

With the boat complete, it has travelled a fair deal (only on land so far) to many trade shows and events in order to rack up support as the ultimate goal is to raise money for charity.

“We have received so many kind donations at the shows we’ve exhibited at, and through our website from people excited by hearing/reading about the project,” says Byass. “Handing the cheques to the charities at the end will be the best bit of the whole project.”

Their original intention was to take part in the Woodvale Challenge Atlantic Rowing Race 2011, a biennial event that sees around 30 boats attempt an Atlantic crossing. But as the project progressed, the pair realised that they wouldn’t have enough time to thoroughly test the boat before the start of the race.

So the crossing has been rescheduled and will take place this year, either in the summer from New York to the UK or in December, going the opposite direction.

“There’s a lot still to do before even thinking about pedalling the boat,” says Byass. “And once all those things are taken care of; we then have to pedal a boat 3,000 miles — scary but exciting too.”

torpedalo.com

From screen to prototype in just six weeks

Default