With automotive engineering on the cusp of a new era. Stephen Holmes speaks to two of the most exciting brands – Polestar and Ford – to gauge how R&D is navigating new engineering challenges and driving new business strategies

The global automotive industry is motoring along at a dizzying pace. New powertrains and fuel storage systems, particularly when it comes to electric vehicles, are no longer futuristic concepts, but a reality that manufacturers have set themselves hard timelines to achieve.

Legendary names, challenger brands and start-ups with exciting new ideas are all fighting for prominence, yet what they all have in common is the driving force of research and development (R&D). In short, new thinking around materials, lightweighting, aerodynamics, electromechanical advances and software lead systems are shaping the future of transport.

The challenger: Polestar

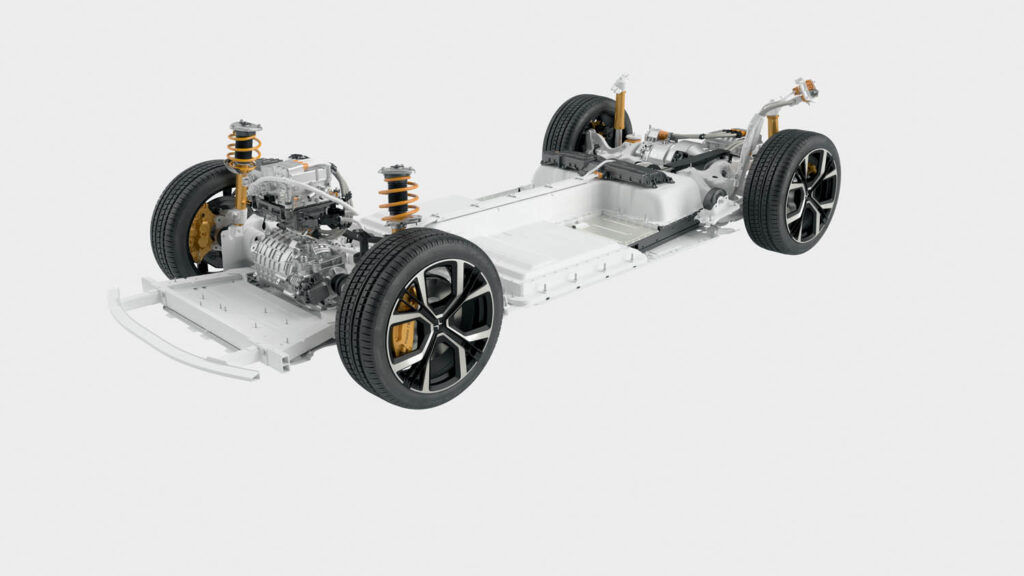

Polestar is one example of a new breed of automotive brands – companies focused on electric performance, whether from fullelectric vehicles (EV) or hybrids.

Arriving fully formed out of parent company Volvo, itself part of the giant Geely Auto Group, its first vehicle, Polestar 1, is a 600bhp hybrid Grand Touring Coupé, with a range of 99 miles on pure electric power – the longest of any hybrid. Its latest model, the nippier, fully electric, fastback Polestar 2 maintains the brand ethos of minimalist styling mixed with an environmental conscience and the latest technology underpinning its drivetrain.

Hans Pehrson has long been a driving force behind electric vehicle technology and new developments within Volvo Cars and at the Geely-owned London Electric Vehicle Company, the brand behind the latest Black Cab to ferry passengers along the UK capital’s rapidly decarbonising streets.

He’s now Polestar head of R&D and responsible for the brand’s electric propulsion strategy. Despite over 30 years in the automotive industry, he certainly isn’t one to cling to the internal combustion engine (ICE).

“The longer you work with cars, and the society we live in, so to speak, you realise there are pros and cons and something that needs to change,” Pehrson says, speaking from Polestar’s R&D base in Gothenburg, Sweden.

“With electrification, we’re in the really early stages of development, so for things that were correct yesterday, we have new findings tomorrow. Even if they look quite similar, there are such big developments, so it’s really exciting to be on that journey.”

Polestar – Sparking changes

The move to full electric is exciting from an engineering perspective, because it’s fun to do something new from a clean sheet of paper, Pehrson says, adding: “or at least much cleaner than from continuous improvements.”

But we have to remember that electric cars also really need continuous improvement, he adds, “not just ours, but all brands.”

Pehrson cites the ability of new EVs to update and adapt using over-the-air (OTA) software updates, enabling them to evolve much like a smartphone or laptop computer does. “You get upgrades and then it feels like your product is getting improved as you own it,” he says. “I think that’s a big shift. I really like that part!”

But the Polestar R&D team is thinking about continuous improvements that go way beyond just software; for example, being able to develop and upgrade existing parts throughout a car’s lifetime that can offer improvements like lower air resistance.

While these would allow the consumer a wider variety of upgrades and variations, ensuring that new parts fit and work alongside existing components seamlessly is another challenge entirely.

Software is key. Polestar uses Dassault Systèmes Catia for its proven track record in addressing design and engineering requirements in the automotive industry, but Pehrson suggests that what’s really important is that designers and engineers have tools that are easy to use.

“If you invest too much in creating a model for simulation or 3D, if the engineers have to invest a lot of effort to create it, then you don’t want to change it. It’s quite natural – we’re a little bit lazy, all of us! It’s so important that the tools are easy to use, easy to change and have quick loops, because we enhance the willingness to learn and improve,” he says.

“That is so important for all the tools that we have in R&D – that they’re helping you to design and try new things.” Virtual testing is at the heart of R&D, and making sure the physical and the digital results match up is something that has improved greatly over the years, he says. “We can delay the [physical] prototypes more and more as we trust the virtual tools more and more.”

The end results still have a part to play in influencing R&D at Polestar, says Pehrson. Once every car is an EV, then sustainability will become the big challenge.

“We have to get people into EVs, improve the ones we have, and then make them really sustainable,” he concludes.

The giant: Ford

Ford is widely credited with the wholesale commercialisation of the internal combustion engine in the automotive field, with its Model T launched over a century ago. Yet despite its historic ties to fossil fuels, the brand has been making rapid progress in developing new vehicle strategies, for EVs and other segments.

Alice Swallow is a Senior Innovation Engineer, based at Ford’s UK site at Dunton. Having begun as a Higher Apprentice in Engineering (winning Great British Woman Apprentice of The Year in 2018) while studying for a BEng in mechanical engineering, she has worked her way up through the company ever since.

With a role that covers chassis development, advanced propulsion systems and digitalisation, Swallow has recently moved to Ford’s UK Innovation team, project managing UK Government advanced R&D pre-programmes – much of which involves research into advanced and composite materials, and lightweighting, with a particular focus on commercial vehicles.

“Our projects are collaborative projects. To be able to utilise government funding through agencies like Innovate UK or the Advanced Propulsion Centre, you have to work collaboratively with industry, which is great because then you can utilise their best strengths,” Swallow says.

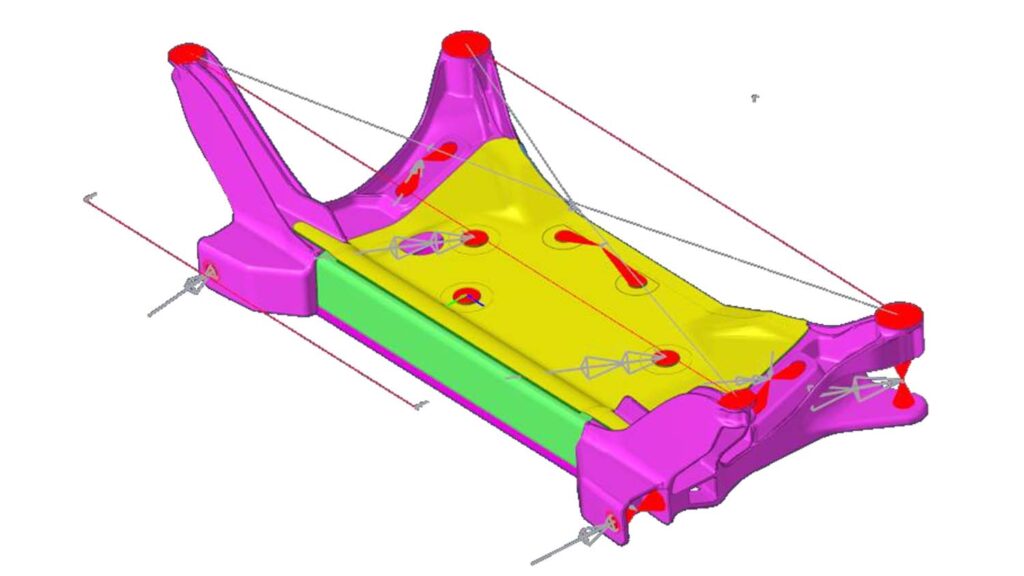

Project CLASS (Composite Lightweight Automotive Suspension System) was the first project Swallow worked on, where the team looked to reduce the weight of a Ford Focus RS rear suspension arm, and investigated whether carbon-fibre Sheet Moulding Compound (SMC) would be suitable for this.

The results of the programme showed that it was more cost-effective and efficient to have a multi-material part, rather than just SMC, because the resulting part would be too thick and take too long to process and manufacture. “So we used pre-preg [carbon fibre], steel and SMC, and compression-moulded all of the components together,” says Swallow.

The optimised design and manufacturing process, developed in conjunction with Warwick Manufacturing Group and Gestamp, enabled the replacement of a multiplepiece fabricated steel component with a single moulding. This work resulted in a weight saving in excess of 35%. Swallow says the team has learnt a lot from that project about how materials are processed, which in turn got them thinking about how they could apply R&D to the production of commercial vehicles.

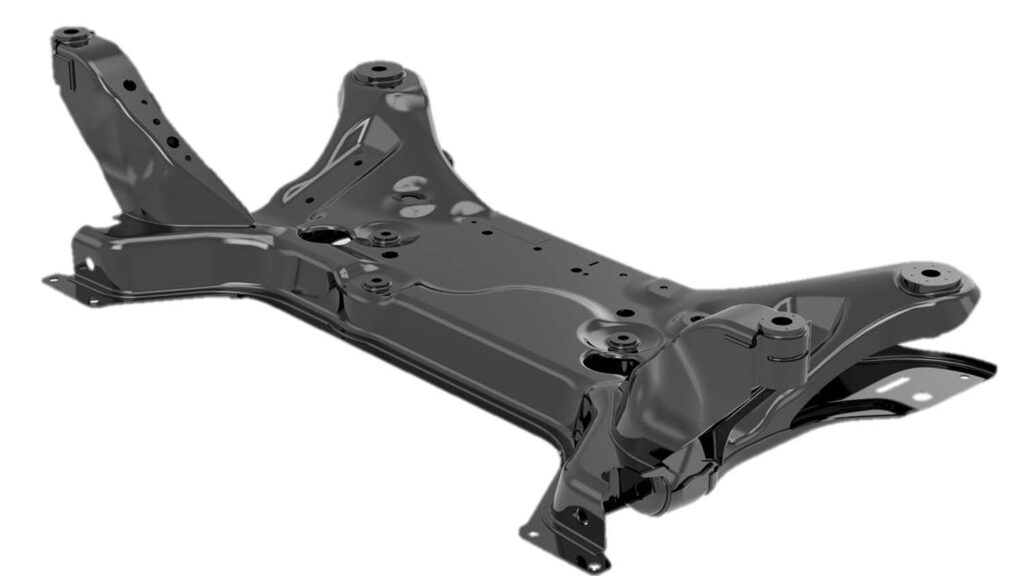

“You could do it in a much more cost-effective and quick enough way that we could meet the Transit production volume targets, and that’s where the chassis project came about,” she says.

As a result of the programme, Swallow’s team then looked at adapting a front sub-frame, a rear dead beam, and a front lower control arm as part of Project CHASSIS, considering various composite materials against their steel component predecessors.

“They perform differently and then they’re processed differently, and also when you have a hybrid of materials, a lot of the time we’d look at an adhesive for the joining, so you’d need to have adhesive simulation as well as obviously materials simulation, just to ensure that its bonded correctly and there’s no issues with shearing or strength requirements – so a lot of CAE for those parts!”

Partnering with existing Tier One suppliers, such as Gestamp on Project CHASSIS, means that Ford’s R&D can benefit from partners’ immediate CAE experience. Gestamp, for example, is Ford’s Tier One supplier for existing steel components, Swallow explains, “so they already have all the requirements that they needed and the CAE for the existing steel parts that they could correlate.”

Simulation and analysis tools are critical to R&D at Ford, but for Swallow, more lifecycle analysis software would be of benefit, to calculate the long-term impact of such projects.

She says: “There’s nothing better to calculate sustainability than the full lifecycle analysis of the part. We’ve done a few investigations on some of the chassis’ components and found that the composite and lightweight components, because they’re so much lighter than the steel predecessor components, mean the CO2 is so much lower, and you get a better lifecycle analysis over time.”

Reduce and replace

Not every workflow change is down to software advancements. In 2020, Ford deployed its considerable engineering knowledge to assist with the global pandemic through the UK government’s Ventilator Challenge.

“That, I think, has changed the R&D process quite a lot, because there’s the expectation that actually we can do R&D in a much quicker timeframe – as stressful as that may be!” she says.

“Definitely digital tools have helped, but for the ventilator project specifically, it was a case of, ‘We have no one working on this line at the moment, what do we do with all this resource? We can have them make ventilators.’

The approach of having a department focus solely on a single project for a set amount of time showed a greater rate of progress, when compared with having R&D teams spread across several projects at once.

An offshoot of this became Project SIREN, which paired Ford with Venari Group’s O&H Vehicle Technology – a specialist in vehicle conversions for ambulances – as well as input from NHS Ambulance Trusts.

The goal was to build a lightweighted ambulance based on the Ford Transit platform, in which the lightweighting plays a very different role to EVs.

The ambulance is an ICE variant, and while it does benefit from reduced CO2 emissions, the key factor is that many people don’t have the drivers licence requirement to drive anything above 3.5 tons.

More ambulance workers can now drive the vehicle, reducing the amount of training and the costs for the NHS of running a heavier vehicle.

Swallow describes Project SIREN as a really exciting “sprint project”. It began towards the end of 2020, and a demonstrator was announced in early February this year. Production models are expected by mid-2021.

Onward journey

The next stage in the move to commercial EVs presents further challenges, given the battle between battery weight, range and the necessary payload for owners who demand the most from their vehicles, which in many cases, are their livelihoods.

“You’re going to be introducing weight of probably upwards 100kg, dependent on the size of the battery, so if you want to keep the same payload that your regular customer is used to for an ICE vehicle, you either need to get that 100kg out or essentially charge them less for the less payload,” explains Swallow.

Ford’s R&D is clearly on the road to finding the right balance with the most recent PHEV Transit, but cost effective lightweighting and materials research will continue to play a big part towards solving the conundrum as technologies evolve.