Splashy can be used for bath time or messy play with a five point harness that keeps children secure

Most young children and their families enjoy bath time but when it comes to those children with additional needs it can be a stressful experience for all involved as they frequently need support to keep them safely upright and comfortable.

Having brought to market several adaptive products in its Firefly range, a bath seat was the next on Leckey’s list.

“We wanted to better support children so they can focus their energy on play, enjoying the sensation of the water and family time,” describes Fiona Bennington, a design engineer at Leckey, a Northern Ireland based manufacturer of clinically focussed, postural supportive products.

The idea for a durable, simple to assemble, easily configurable and lightweight bath seat actually came from a fellow member of the design team David Turner who had personally experienced problems when bathing his young daughter. “Many of our product ideas come from parents, some are internal and some come from charities,” comments Bennington.

Firefly has a large and vibrant community of parents on social media that it draws on to provide feedback on ideas and concepts and then, further along in the design process, to help test prototypes.

“One of our biggest challenges is always designing a product that looks good and also suits the majority of possible users. Our kids have a wide variety of complex needs and it’s challenging designing to suit everyone.

Thankfully we have a great community in Firefly, literally thousands of families who want to help us with input, testing and advice,” says Bennington.

Splashy is available in three mix and match colours

Design goals

During the initial design stage, surveys were carried out with parents asking them what they’d like the seat to feature. Most responded that they wanted something better than the current medical products available on the NHS, which are heavy, unattractive and take up most of the bath leaving no room to play and for siblings to bath together.

“One of the design goals for the Firefly brand in general is to make products that don’t look medical because one of the things parents kept telling us, especially with the bath seat, was that all you have to do to tell they have a disabled child is walk into their bathroom.

“It’s a big frustration for them and so we aim to create something that would be at a level that if a child sees another child using it, they would want to get in it even if they are neurotypical,” comments Bennington.

As well as working with a community of parents, the designers also have therapists as part of their team who they consult with at the start of the design process and then throughout. As they are creating medical products, there is a great deal of focus on testing, trialling and clinical feedback.

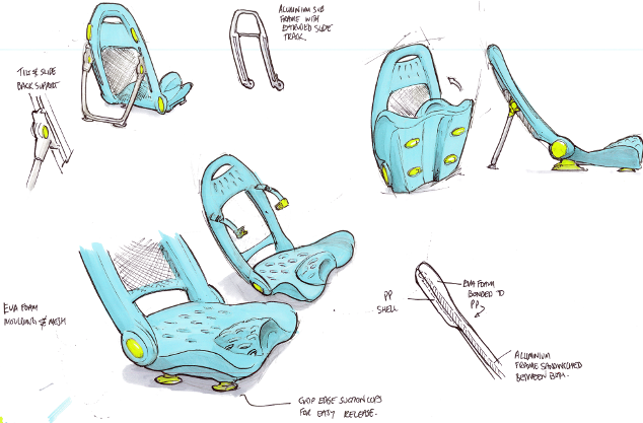

Early sketches

Concept stage

Having carried out its initial survey with the Firefly community, the design team took the top five features requested and created concepts that addressed them.

Concepts are drawn on paper first and the team will also create crude 1:1 hand drawn paper models to determine size and dimensions before getting into SolidWorks.

“I do tend to use CAD at this stage but only as a tool to print out rough sizing guidelines that we then draw the product onto by hand in 1:1 scale.

“I would then scan and import these back in to generate the sketches that drive the CAD model. In this way our hand drawings become our CAD,” explains Bennington.

Rather fortuitously, the Firefly design office has a trade bathroom supplier next door with 15 to 20 baths and showers in its showroom. These proved very handy when trialling the initial Splashy prototypes.

“We were taking different prototypes in to check that they would fit into the baths and sometimes even getting in ourselves to see if they could easily be tipped over.

They treated us with concern in the early days,” laughs Bennington, “but they became less suspicious when we bought a few things to help with the project such as a bath and an immersion heater for the testing of units in hot water later on. The plumbing advice they gave was also actually really helpful!”

Splashy sits low to the base of the bath so the child can sit in the water and its compact design also means siblings can bath together

Sitting confortably

One of the most requested features that emerged from the surveys and discussions with families and therapists was the ability for the bath seat to recline and for it to be as confi gurable as possible.

The designers achieved this by creating a base unit that enables users to easily switch between 26 recline positions, from 140 degrees full recline to 106 degrees upright. All the bubble holes on the foam cover unit are then actually attachment points for the harness or bumpers.

“Parents can set the seat up any way they need to suit their child. The four detachable foam bumpers can be located in a variety of places to provide additional support and the harness can be three or fi ve point and attached almost anywhere,” explains Benningotn.

However, the foam cover unit actually posed one of the biggest challenges in this project. The seat structure is made from glass filled polypropylene, which has been used successfully in other seat products in the Firefly range, but for the material used for the cover unit the design team wanted something comfortable and soft that was also waterproof and rigid. They looked at various products for inspiration, particularly the Crocs brand of sandals but finding a supplier that could provide that material in the part sizes they needed was the difficult part.

“In the early days we probably spoke to ten different suppliers whose machines could produce small parts at high volume, as they are used to producing shoe soles, but what we wanted were big parts at a lower volume.

“We had a lot of learning to do about what was possible and what wasn’t but we did succeed in finding a suitable supplier in the Far East,” says Bennington.

In the meantime, the design team had selected the final prototype that demonstrated the most promise and brought it into SolidWorks to create the 3D model. Data was then sent to the in-house 3D printers, which would print prototypes, sometimes even overnight, for testing or review as soon as the next day.

Although 3D printing played a big part in the Splashy design process, it is still a relatively new capability for the team to have in-house. As Bennington explains, just over a year ago the design offi ce invested in two desktop Ultimaker machines as they seemed a good budget option. “We thought we’d just give them a try but they paid for themselves in about two weeks,” she says.

“We’ve since bought a medium and large Gigabot from Re:3D. It’s an industrial 3D printer that off ers a substantial build envelope which was what we wanted, and it was a Kickstarter project that had some great feedback. I have to admit, that it’s been brilliant having them. They have been invaluable in the process.”

Typically, the design team would print a prototype and then test it in-house before giving it to users and therapists.

With the feedback garnered, they’d then refi ne the 3D model in SolidWorks and print more prototypes. Eventually they reached a stage when the Gigabots were used to make several units which went out for long term trials.

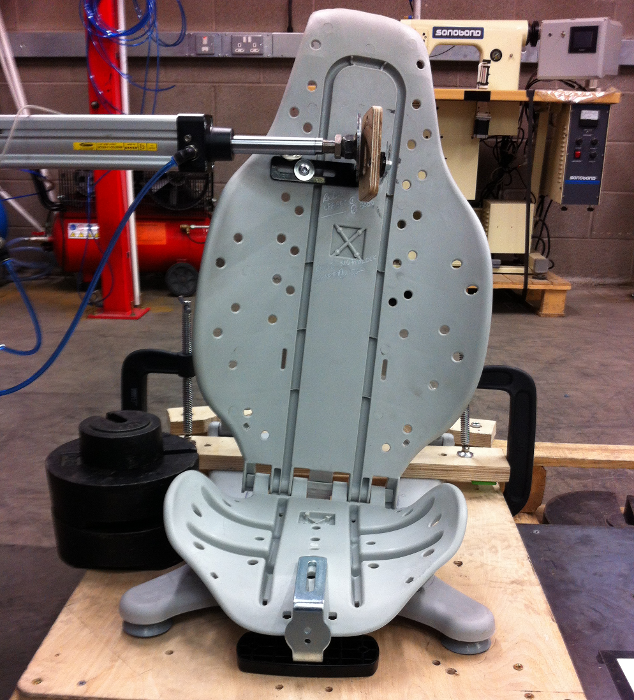

A prototype undergoing 10,000 cycle side load testing

Optimistic designs

Within SolidWorks, the team also utilised the FEA capability to optimise designs. “We need to make sure that the seat can withstand a 30kg child moving around. That’s demanding enough so it is helpful to have FEA in-house to be able to check those things and also other critical features.

“But we’ll never use FEA in isolation – we’ll always produce a machined part or a prototype for testing to confi rm that the FEA is telling us the truth. A problem we encountered with this project was that the product passed all of our FEA and in-house physical testing but once we started to take some of the early production units out we realised there was an issue with the way people use the product rather than the kind of abuse we imagined it would go through. So, we can’t just rely solely on virtual testing or even in-house testing for that matter, we also need to do trials,” comments Bennington.

With the final parts ready, files were sent to the toolmaker which used Autodesk Moldflow to simulate the filling phase of the injection moulding process to check that the parts would be suitable for moulding in the way the design team intended. “In this project, I’m most pleased with what we achieved with the foam moulding because it really seemed like it might not be possible at one stage.

“As a design team we really didn’t want to compromise on the foam covers and as a result it took us a little longer to close the project out, but I really do think we have a better product as a result of staying true to our design intent,” says Bennington.

Once the parts were made they were shipped back to Leckey for configuration and assembly. The seat covers and harnesses are available in three bright colours that users can mix and match – an option almost unheard of in the healthcare industry.

Working so closely with users and therapists throughout the development process means that essentially the Splashy has been co-created with them and this is possibly why it has been so positively received since launch in January 2017.

From Bennington’s point of view, it’s rewarding to see the photos and videos that parents post on social media of their children enjoying bath time.

“With our products we have so much opportunity to make a real difference to kids and families and so it’s definitely worth the effort.”

Leckey designs a kids bath seat to make bath time fun

Default