Imagine the feeling of scuba diving and riding a motorbike at the same time. This is what paramotoring feels like according to Jim Edmondson, managing director of Parajet International, a Dorset-based paramotor manufacturer.

Parajet Team and Red Bull Air Force pilot Othar Lawrence flying the new Zenith paramotor

“It’s a very liberating experience because you have nothing around you just the ground below. You can go wherever you want and experience the world from a completely different perspective.”

The sport of paramotoring is relatively new having been introduced in the 1980s. Essentially it is a powered paraglider with a propeller and engine worn like a backpack.

The pilot then flies by means of a harness that is attached to a paraglider wing. Depending on the hot air rising, the engine can be turned off and then on again when lift is needed.

Paramotors are usually flown between 500 to 1,000 feet above the ground at speeds of up to 50mph.

“The thing that makes the paramotor very exciting is that it’s the only fully-powered aircraft you can pack down and fit in the boot of your car. Also, as it’s foot launched, you don’t need a licence to fly it,” says Edmondson.

Humble beginnings

The Parajet story began in 2000 when aviation engineer and paramotoring fanatic Gilo Cardozo secured the UK distribution rights for the Whisper DK, a paramotor produced by the Japanese electronics company Daiichi Kosho.

However, he soon realised that he could design and develop something better himself so set up Parajet in order to build a paramotor from the ground up with its own bespoke engine.

Following an expedition to the summit of Mount Everest with adventurer Bear Grylls (below), which Parajet developed the paramotors for, the company really took off.

Having moved from its smaller premises in Wiltshire, all of Parajet’s products are now made out of its North Dorset-based factory, which conveniently features a landing strip right outside for the testing of prototypes.

Parajet’s latest model is the Zenith. Although Edmondson admits that the company was doing very well with its Volution and Cyclone ranges and didn’t necessarily need to develop a new product, there were a few things they wanted to improve on.

One was tucking the engine and fuel tank up really high to create a minimal ‘footprint’ behind the pilot. This would result in cleaner airflow, less drag and better fuel economy.

Another was to look at the construction of the metal chassis and frame itself, which up until this point had been welded together.

“When we brought out the Volution six years ago it was really state-of-the-art and we didn’t think we’d do anything afterwards but the difficulty with it being welded is that if one part breaks, a whole section needs to be made up again,” describes Edmondson.

Technology push

So just over two years ago when Parajet started on the Zenith project, the initial intention was to fabricate all the plug-and-play parts in metal so that they could click together.

This meant that parts could be easily replaced if they broke. “But when we started looking at it, we reckoned we could probably make all the parts on the CNC machine.

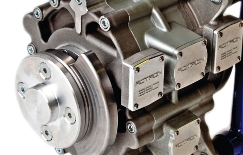

From that point the whole project just snowballed.” However, the ability to construct a 90 per cent CNC-machined paramotor was only possible due to the decrease in price of CAD software and CNC machines.

The company still had a seat of AutoCAD, which one of its engineers prefered working in especially as it’s good for doing castings, but for the rest of the design team Parajet invested in SolidWorks.

“Before it was so expensive that it wouldn’t have been possible for a small company like ourselves to invest in technology like that but now we have four CAD guys and six CNC machines working full time,” he says.

“It wouldn’t have been possible to do this before but we really wanted to use the technology to push our products forward.”

Brand new process

Once the design team had created their CAD models the data was sent to the CNC machine for the parts to be cut out.

Andrew Scaramanga, Parajet’s production manager who has over 30 years of CAD design and CNC machining experience, came up with the idea of creating a vacuum bed, which was inspired by previous experience in woodworking.

“With thin flat materials it’s very difficult to hold them down because they flick up. So, a large sheet of material is placed on the vacuum bed or table at the bottom of the machine and the air is sucked out through the open holes.

That atmospheric pressure clamps the material down. We can then machine the outside of the sheet and between the seals too,” explains Scaramanga. “So the work is held in place and even the bits that are cut off stay there and they don’t fl ick up.”

The vacuum bed worked very well during the build process as it has meant less work for the machine operator when removing and replacing new materials.

Before they would have had to undo all the bolts, put the material into place and tighten it all up again whereas with the vacuum the material just auto locates into position.

“Basically Andrew really wanted to make a vacuum bed and really pushed for us to do it. It’s great that he did as it’s been an amazing success,” says Edmondson.

Small but dynamic

Cardozo has always had a ‘let’s do it’ approach to challenges whether it be paramotoring to the summit of Everest or trying new manufacturing processes such as the vacuum bed.

His employees feel the same way and are always up for being daring and trying new ways of doing things. “Making everything ourselves in-house is an uphill struggle but the challenge is fun,” comments Edmondson.

“We are a company that is very much about having fun. We of course have to make money to be able to pay everybody but it’s more about enjoying ourselves and striving for perfection in everything we do.”

Most of the components on the Zenith are designed and manufactured in-house. As Edmondson explains, unlike motorbikes, which have lots of standard parts, if a new

component is needed one has to be made.

“We do buy in the engines and the sleeveless netting but we do the sewing internally. We’ve just bought an industrial sewing machine, which means poor old George over in the factory has now become a seamstress,” he smiles.

Developing the components in-house results in some innovative solutions such as the quick release fuel tank with its bayonet-style locking pin. Parajet’s team couldn’t source one as strong as they wanted so engineered it themselves.

The locking mechanism was designed in such a way that the pin always remains extremely strong. To disengage unintentionally either the pins must break or the sleeve into which the connector slides must be distorted or torn enough to free the pins.

It is a feature that Parajet claims will offer peace of mind to the pilot.

Similarly, other features such as the hinge blocks, lightweight chassis, aerofoil cage and adjustable ‘swanneck’ pivot arms all give the Zenith its high strength and responsiveness whilst also making it compact and aeroefficient.

“I would say that the Zenith is probably the most technologically advanced paramotor when you consider the amount of design and engineering work that has gone into its creation,” says Edmondson.

Testing testing testing

A lot of these features were actually perfected following extensive testing.

The design team work alongside Parajet’s team of experienced pilots and use their feedback to improve the design so that they end up with a paramotor that reflects the needs of those who’ll be flying them.

“The Zenith took two years to design and the reason it took so long is because it was a case of making prototypes and then fl ying them. Prototypes were also taken to different parts of the world to test,” says Edmondson.

Following a small batch production and meticulous assembly procedures, the Zenith was launched in May 2012. With a price tag of £5,399 customers can choose from three engines and personalise their paramotor through the numerous anodised colour combinations.

Parajet has a worldwide distribution network of flying schools which its products are sold through including 36 in the US where they are very popular.

In the seven months since launch, Edmondson says that 200 Zenith paramotors will have left the factory. In 2013 they plan to double that amount and also launch a Bear Grylls version, which will be sold through his website (beargrylls.com).

Winning formula

The Zenith has been flown in many parts of the world from over the African desserts to the Bonneville Salt Flats in Utah and along the Australian coastline to high above the Rhône-Alpes.

And just a month after it was launched in June Parajet team pilot Dean Eldridge won the 2012 British Open Paramotor Championships and in September he went on to win the World Fly Games in Canada.

As fellow Parajet team pilot, Maren Ludwig, says of the Zenith: “There’s certainly a few unique and impressive features that I really appreciate and the attention to detail in general.

But even though there’s quite a few features that stand out, it’s all of those together that make the Zenith so special and incredibly fun to fly.”

This is high praise indeed especially for Edmondson who wants the products that Parajet manufactures to be fun to fl y but also for the employees to have fun whilst designing them.

This was certainly evident to industrial designer Lloyd Pennington of Buff Design who came across a Zenith whilst at the Pentillie Festival of Speed in North Cornwall during September:

“It would seem apparent that the folks at Parajet had a lot of fun bringing such a beautifully designed and manufactured product to market. I think those companies that clearly love doing what they do make the best stuff .”

Mission Everest

In 2007, to capture the imagination of the world and the hearts of its employees GKN, a British automotive and aerospace components company, teamed up with the explorer Bear Grylls for the Mission Everest expedition.

The mission was to fly to a height above the summit of the world’s highest mountain using paramotors.

The highest a paramotor had flown before was just over 20,000 feet, nearly 10,000 feet below the summit of Everest.

To develop a paramotor that could reach that height in temperatures of -40oC and wind speeds of up to 175mph would be a very tough challenge and the man to take on that challenge was Gilo Cardozo, Parajet’s founder.

Together with his team of engineers, they developed two specially adapted paramotors, one for him as he was going to accompany Grylls, complete with custom made single-motor, 85 horsepower, four-stroke rotary engines.

On 14 May 2007 the two pilots took off and in a flight that lasted four hours they achieved a paramotoring world record of 29,494 feet. As well as a huge personal achievement for Cardozo it also helped put his company on the map especially as the whole mission was filmed for television.

“The documentary on the Discovery Channel had millions of views and so it really helped us get exposure for our company.

From there we started distributing our paramotors all over the world,” says Jim Edmondson, Parajet’s managing director.

The bigger picture

Parajet International’s parent company is Gilo Industries Group.

Founded by Gilo Cardozo, there are four companies within the group including: Gilo Industries Research, a research and development company; Parajet International, a paramotor manufacturer; Parajet Automotive, which designed and manufactured the SkyCar, a fully road legal car with aviation technology that in 2009 went on a 7,000km expedition from London to Timbuktu (work is currently underway for a new version but at the moment it’s top secret); and Rotron, a rotary engine manufacturer for recreational aviation as well as military applications.

Rotron was set up in 2009 on the back of the rotary engine Cardozo and his Parajet engineers had developed for the Mission Everest paramotor.

Ironically, it no longer produces engines for its own paramotors but for various aircraft and automotive clients worldwide. “We are currently the most advanced engine technology provider in the world.

We’ve just taken on a major contract for the design of engines for military unmanned aircraft,” says Jim Edmondson, who as well as being managing director of Parajet International is also the strategy director at the Gilo Industries Group.

All of Gilo Industries Group’s products are designed and manufactured in its Dorset-based factory.

“We used to have all the companies separate with their own design teams but when the management company came along we chucked all the designers and engineers into one room.

So, they now resource across everything and have a hand in developing all our products,” explains Edmondson.

The flyaway success of Parajet’s CNC-machined paramotor

Default