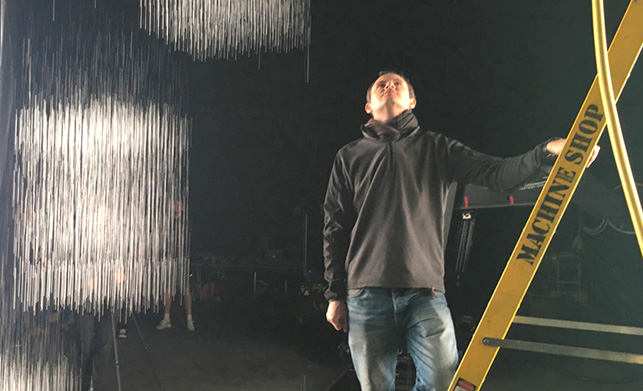

As the London summer heatwave takes the thermometer inside Machine Shop’s offices past 28C, it’s ironic that we’re sat looking at one of the most refreshing advertisements of the last few years.

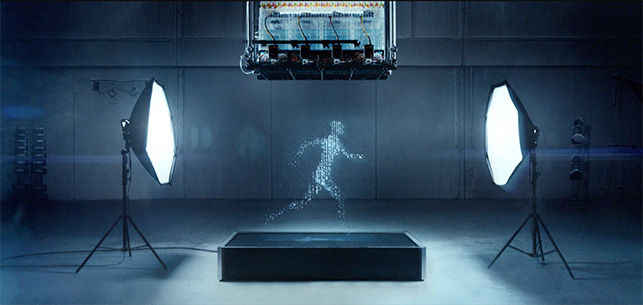

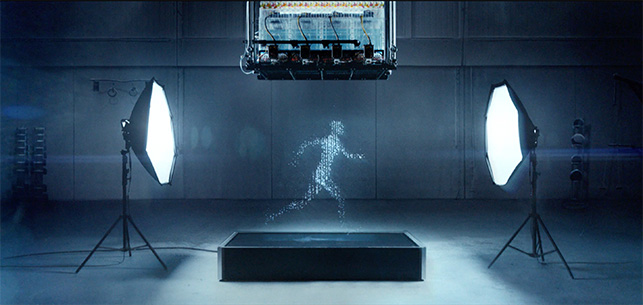

The company’s special effects creators, prop builders and product engineers combined to build the ‘Rain Projector’ used in Gatorade’s Water Made Active campaign for its G Active drink.

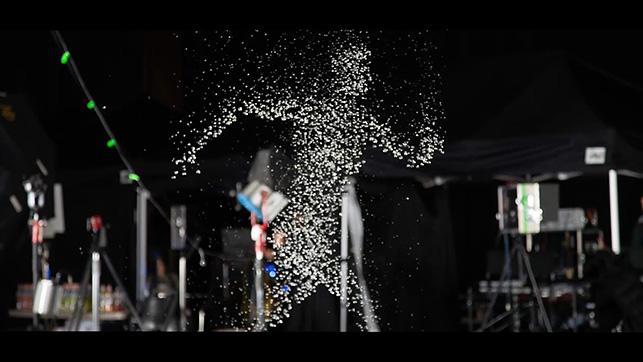

Droplets of the energy drink fall like rain, forming shapes captured by cameras, frame by frame, transforming them with stop motion flash photography into a running, jumping, kickboxing human form.

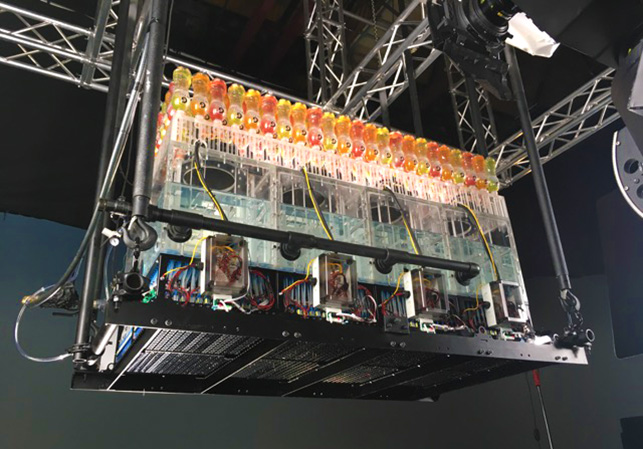

The machine creating the droplets became known as the 3D Liquid Printer – 8 module tanks sat suspended on a rig, firing 2,048 electronically programmed water switches, and built from over 20,000 individual parts and custom- made components.

Machine Shop has been splashing liquids, blowing things up and making all kinds of models and solutions for visual media since 1993, and this example is typical of the unique, one-off projects it undertakes for big-name brands.

“When you see the [special effects in an] advert you think ‘Oh, that’s nice’, or you don’t even think about it,” says Patrick Thursby, project manager of Machine Shop’s Special Projects division.

“You don’t see that, in order to make that ‘swirl of chocolate’ or whatever it might be on screen, you’ve got six motors above it and it’s pouring fluid down a plastic shape in order to get the shot.”

For the Gatorade project, Machine Shop had to achieve the perfect shot literally thousands of times.

Programming Challenge

Working with the London-based production company Unit9, a lot of concept ideas were considered in what was a fairly open brief that began with solving the programming element.

“They provided us with the 3D data for the figure – motion capture applied on to a 3D model – and passed us each frame as a mesh,” says Thursby. “We had to develop some software to then slice that.”

With the help of specialist electronics programmer Will Gallia, the release timings of the slices were processed further, adding a further layer of complexity as the team sought to give the illusion of counteracting gravity.

The figures were divided evenly, layer by layer, in the software, but this left the problem of ‘spread’ to deal with. When the first drops have left the machine and are near the bottom, they’re moving faster than the last drops still at the top.

The release timings of the slices were processed further, adding a further layer of complexity as the team sought to give the illusion of counteracting gravity.

“At that stage, we weren’t working with models, we were just working with maths. ‘Here’s a grid of 1s and 0s’,” says Thursby. “It wasn’t until we got a 3D model and started to try and process that, that we knew it was going to work.”

The physical Liquid Printer was constructed at Machine Shop’s base in West London, a looping layout of workshop spaces set up to cover all angles, from traditional model making and casting skills, to dedicated wood, metal and electrical shops.

The original prototype module from the advertisement sits in the main workbench space, a room adorned with all kinds of models and sculptures from previous television, film and ad work.

The most striking thing about the prototype itself is the amount of wiring involved for a project in which the main focus is liquid.

Each wire connects the controlling computer boards directly to the solenoids managing the precise dropping of liquid two to three times a second from the pressurised tank above. Multiply this module by eight, and the complexity of the build becomes apparent.

Machine Shop – time Pressures

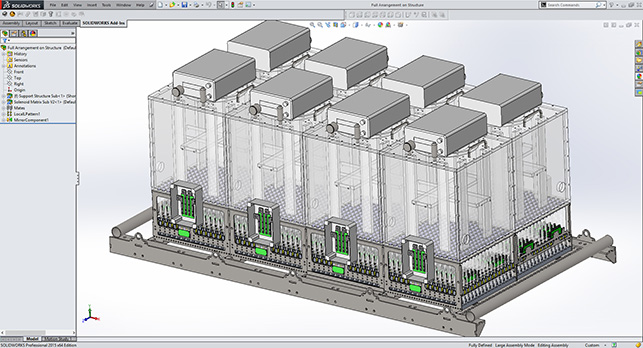

Designed in SolidWorks, a working time constraint of three weeks meant that the CAD model missed out a lot of finer details, with aspects like modelling individual cables abandoned and accounted for by measured gaps.

“We had such little time, as I was out there building it with the guys,” explains Machine Shop project manager Steve Loible, pulling up the models to his workstation screen. “We use it to the best of our advantage, but time’s limited.”

The job reference number 5446 needs to be dug out first, highlighting the pace at which Machine Shop tackles projects: a conservative estimate puts it around 6,000 jobs over the past 25 years, averaging four and a half different jobs per week.

“We couldn’t do any flow calculations or anything like that, or routing electronics. If we’d had a year, I would’ve modelled everything, but this was the detail I could fit in the time, which was all the critical things.”

The CAD model proved essential for the build, giving accurate measurements, data for CNC machining, laser cutting and weights to pre-empt the full water-filled load that would eventually be balanced on the filming rig.

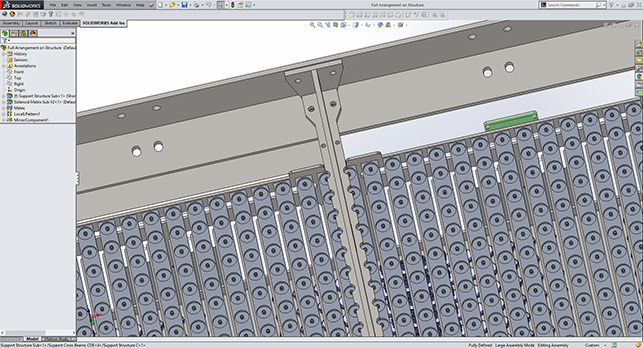

The finished modules are very tightly placed together – consciously designed so that when assembled the gaps between the nozzles was seamless. The joining wall for the modules, meanwhile, was designed as an I-beam with cut-outs at intervals to make sure there were no gaps between the nozzles between modules.

“There were loads of little details when doing it. You just couldn’t do it otherwise, which is the great thing about SolidWorks,” concludes Loible.

The Need For Speed

Placement within the form became a tricky process; elements like finding the right size solenoid became vital to achieving densely packed droplets, yet doing so in such a tight space brought uncertainty over what would happen with the level of magnetism.

“We spent three weeks with one solenoid trying different nozzle sizes, nozzle heights, different flow rates, different fluids,” recounts Thursby.

A local supplier Machine Shop uses for a lot of fine engineering parts was able to provide the different shaped nozzles – rounded edges, sloped edges, different diameters and so on. From there, it was a case of hands-on testing before delivery to the studio.

Machine Shop’s location, in West London’s Park Royal, an industrial pocket of craftsmen and materials suppliers, helps address the urgency of its projects. As Thursby explains: “You can get pretty much everything the same day, which means we can work very, very quickly.”

Speed translates into results for Machine Shop, giving the company the power to make it rain on command – even on the sunniest days.