How Yves Behar & Herman Miller used an Eco-dematerialised design approach to create the Sayl chair with fewer parts and fewer materials. By Tanya Weaver.

Take one industrial designer renowned for his innovative approach and one manufacturer heralded for its environmental policy and the result is something rather ground breaking – the SAYL office chair. During its design process Yves Behar, founder of San Francisco-based design firm fuseproject, together with the development team at Herman Miller, scrutinised every part of the chair to ensure that it would be the lightest, strongest and most sustainable possible. Certainly its most innovative feature is the full suspension back, which is literally frameless.

Although Herman Miller has been environmentally aware since it was first founded in Michigan in 1905, it was in 2000 that it publicly stated its intention to become a sustainable business. Soon after, the Design for the Environment (DfE) team was established to develop environmentally sensitive design standards for new and existing products. The principles that were to be followed were laid out by Bill McDonough, an environmental designer, and Michael Braungart, an environmental chemist, in their book ‘Cradle to Cradle: Remaking the Way we Make Things’.

The ‘cradle to cradle’ paradigm is modelled on nature where nothing goes to waste; one organism’s waste is another’s food. So, for Herman Miller this meant focusing on using safe materials that can be disassembled and then recycled or composted. “Cradle to Cradle is a simple design protocol. It places a large emphasis on understanding the chemicals that end up in our products,” explains Gabe Wing, Herman Miller’s senior environmental manager. “What we are trying to do is work with our supply chain to dig back and make sure that we have the ability to catalogue every single ingredient that ends up in our products down to one hundred parts per million.”

For Behar, embarking on the SAYL design process, the aim was to create a beautifully designed yet comfortable chair that would not only be sustainable but could also be sold at an attainable price. “Right from the start I looked for ways to reduce the amount of materials and lower the weight. For inspiration to get there I looked at the way suspension bridges are constructed,” explains Behar.

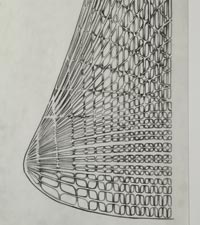

“I started looking at ways that you could have a tower system that could essentially carry loads. This meant creating the main structure for the chair in a much more efficient way than the way it has been built before. That is when I realised that I could use that inspiration to build what is essentially a suspension frameless back for the chair,” he adds.

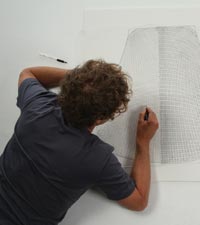

Having examined how people sit and work at their desks, Behar and his design team turned to their pens and sketchbooks and created drawing after drawing. They re-examined everything from the back, seat and controls down to the smallest details and in the process over 1,000 sketches were produced.

“If you want to truly innovate this cannot be done on a computer. It is really a process of experimentation and very much like laboratory work,” argues Behar. “You need to be able to quickly iterate, to try different methods, to fail quickly and that isn’t something that can be done on a computer. With drawings you can quickly explore different ideas – both structural and visual.”

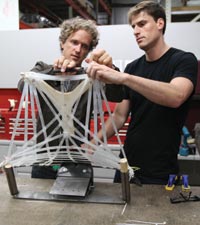

Alongside the sketching over 100 prototypes were built. “A good half of which were done in our design studio to allow us to experiment and try different methodologies. This helped to prove that the suspension worked both structurally and also ergonomically,” says Behar.

So, the design tools used to really invent the chair were sketches and prototypes. Thereafter, once the principles had been decided, CAD was used to model and refine the product. Simulation was carried out both on the computer and in laboratories, or what Behar refers to as torture chambers. “The parts get tested to one million to one million and a half cycles, which is enormous. But we need this kind of cycle testing in order to have the 12 year warranty that Herman Miller wanted for the chair,” says Behar.

The chair is 30% lighter than most other chairs in its category because of this eco-dematerialised approach

Through all this sketching, prototyping and designing, the fuseproject team worked very closely with the development teams at Herman Miller. “The greatest breakthroughs come from great collaborations and partnerships. While we were really experimenting and pushing the bounds of what may be possible to do or to build, Herman Miller trusted us and encouraged us and supported us in the exercise,” he comments. “I think the best work comes from this type of close collaboration and trust. This is really where you can stretch what’s possible.”

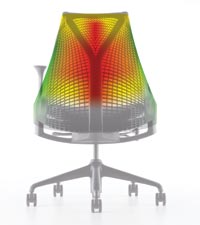

For Behar certainly the most challenging part of the design was creating the structure for the back. This was uncharted territory and required a great deal of hard work and experimentation with different materials. The back is moulded in one piece in polyurethane and, through injection moulding, different degrees of tensions have been infused directly into the material. This innovation, dubbed the 3D intelligent suspension back, enables it to adapt to the user’s shape and movements. With no rigid exterior frame the back suspends and supports, in the same way as a suspension bridge does.

“With the suspension back material we were able to get a lot of what I call 3D intelligent performance out of it because we could build very specific ergonomic responses within the material. You can’t do that with formal mesh or hard plastic but with an injected material we were able to create a completely different type of feel depending on different areas of the back,” explains Behar.

Although that aspect of the design was particularly challenging, Behar admits that the entire process was quite challenging. “Creating a product that was innovative and affordable at the same time was a tremendous challenge,” he says. “All throughout when you are inventing you never know what the road is to get there. For example, there are many different materials and different approaches that can be used and that meant a constant state of flux between things that may work and things that may fail.”

1. Yves Behar, founder of San Francisco-based design firm fuseproject

2. 1,000 sketches were produced in the conceptual design phase

3. Another sketch from the conceptual design phase

4. Over 100 physical prototypes were built

5. Another physical prototype

6. Prototype chair components

7. Finite Element Analysis (FEA) of the 3D intelligent suspension back

8. Inside the test laboratory

9. Sayl chair production line

10. The full suspension back is literally frameless

11. With a price tag of £350 the Sayl chair is attainable as well as sustainable

“I think the key to handling these types of challenges is having a trust and a vision for the final result. Continue to iterate and be comfortable with failing knowing that eventually you will succeed,” he adds.

Upholding the DfE protocol, SAYL is designed so that 93% of the suspension back is recyclable. However, sustainable design is not only about selecting the most environmentally-friendly materials it is more about using the least amount or lightest materials possible. This meant removing any unnecessary components yet still delivering a high level of performance and aesthetics.

“Eco-dematerialised is a concept that we brought to the table and fully applied to the chair,” says Behar. “We looked at every part and built it to be the most efficient relative to the other parts on the chair,” says Behar. “A lot of chairs are made of existing components, which is highly inefficient. We were able to really craft every part of interaction between parts to maximise their combined structural and engineering integrity.”

This process of elimination not only meant using fewer materials but also involved hollowing out a lot of these materials. “The chair is 30% lighter than most other chairs in its category because of this eco-dematerialised approach,” adds Behar.

Throughout this development process Herman Miller also carried out Life Cycle Assessments (LCA) of the product. The software tool it uses to analyse the entire LCA of its products as well as its facilities and processes is GaBi from PE International. “What we have found with most of our products is that over 80% of our impacts are upstream of us. So, in order to really change the way our products impact the planet, we have to ask our material suppliers to not only share their chemical recipes but start adopting sustainable practices too,” says Wing.

“It becomes obvious when you see the amount of input mass it takes to make something like the SAYL chair. So, if the finished product is roughly 16kg there is over 1,000kg of ‘stuff’ that we have to pull out of the ground in order to make it. It’s a real eye opener and it’s not just us – we have a lot of opportunity here to eliminate waste inside our value chain which will ultimately lower cost and reduce impact on the environment,” says Wing.

SAYL chairs are being manufactured in their entirety on three continents. This reduces the CO2 impact associated with transportation and shipping. “All of our global operations are powered through some form of renewable energy. But it’s not just about using green energy, we are also trying to reduce the amount of energy needed for manufacturing,” says Wing.

The SAYL chair was launched in October 2010 with a price tag of £350. Judging by the positive response it has received, it looks as though Behar has achieved his goal of creating an innovative chair that was both sustainable and attainable. So, what advice would he give to designers who also want to tread a more sustainable path? “My advice is to essentially look at the entire offering, the entire experience, the entire manufacturing process. To get really involved in the processes, the distribution systems, manufacturing and the logistics because once you understand these you will find some creative solutions that will make a difference. It will allow a product or an experience to be conceived and received as something that is truly a step forward towards sustainability,” he says.

As for Herman Miller, SAYL is yet another product that demonstrates its sustainable business practices. “We aren’t the sustainable business we want to be and our products aren’t as sustainable as we want them to be but I think we are well on our way,” concludes Wing.

www.hermanmiller.co.uk | www.fuseproject.com

Using an Eco-dematerialised design approach to create the Sayl chair with fewer parts and fewer materials.

No