Extravehicular activity

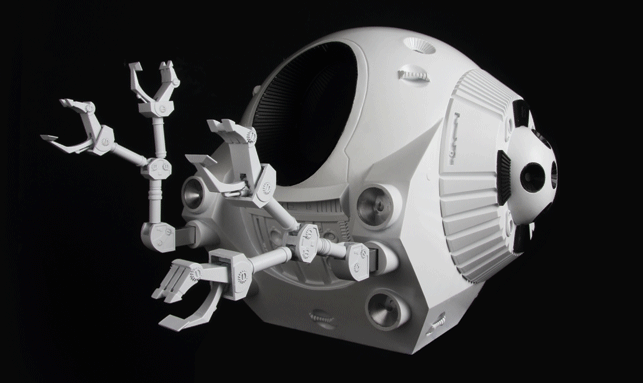

With its poseable arms, clamping claws and LED-lit headlights, Mark Yeo’s EVA Pod model is a replica prop of the original studio-scale model used in the film, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’

In director Stanley Kubrick’s 1968 sci-fi masterpiece, ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’, the three Extravehicular Activity Pods (or EVA Pods) used by the Discovery One’s crew to conduct maintenance tasks outside the main spacecraft all meet with disaster.

Mark Yeo’s model of an EVA Pod fared rather better at the New Blades exhibition for emerging modelmaking talent, held at Holborn Studios in London in June. Yeo took home three awards from the show: Best Use of Laser, the Asylum Creative Prize and Best Product Model.

With its poseable arms, clamping claws and LED-lit headlights, Yeo’s model is a replica prop of the original studio-scale model used in the film. It was commissioned by author Piers Bizony, to use at the launch event for his forthcoming limited-edition book, The Making of Stanley Kubrick’s ‘2001: A Space Odyssey’. Bizony was able to provide Mark Yeo with access to a huge variety of photos and drawings of the original EVA Pod models.

Yeo used Rhino to produce an initial 3D model of the EVA Pod, allowing him to assess how individual sections might be built. The design was split into several main sections as well as a range of detailed components that would be added separately. CNC-milled chemiwood was used for the base of the pod, while moulding and casting was used to duplicate the side panels. A great deal of the front-panel detail, meanwhile, was added using laser-cut acrylic. The black window bevel was 3D-printed on an Ultimaker 2.

The EVA Pod’s moving claws and handles were modelled separately in SolidWorks, where mechanical details were added, before being 3D printed on a Stratasys Objet24, along with its eight rocket thrusters.

“Considering the angles and complex curves in this model, 3D modelling and printing aided the project massively – in the thought process just as much as in the build process,” says Yeo.

cargocollective.com | markyeomodelmaker

Blades of glory

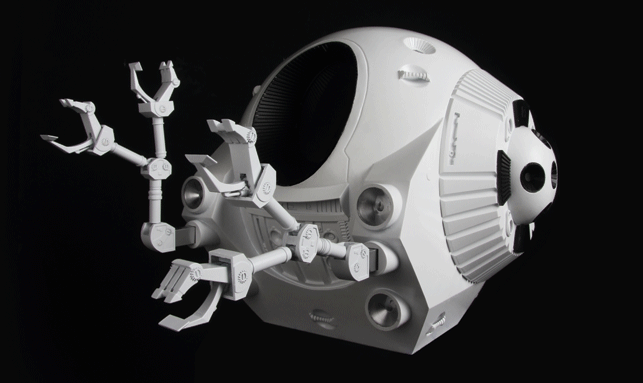

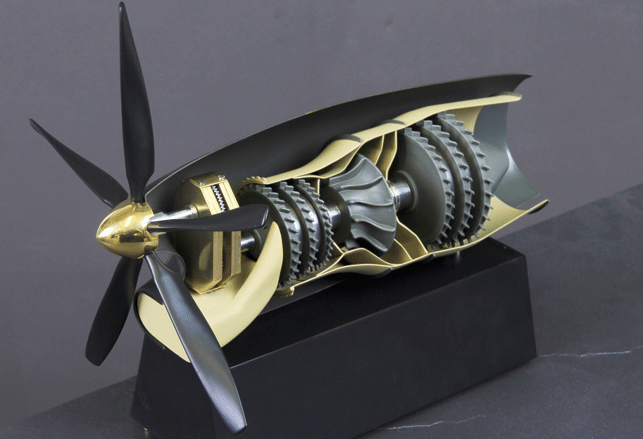

Jack White’s airplane nose cone drew praise from the New Blades 2015 judges for its attention to technically accurate detail

Jack White’s Hartzell Airplane cone stood out at New Blades 2015 for its attention to technically accurate detail. It also scooped its creator the award for Best Use of New Technology.

White’s first aim was to show how pitch is altered within an aircraft nose cone using a digital model. The 3D CAD was fully built, rendered and animated in SolidWorks, showing the mechanism in action with exploded component views.

He then moved on to building a more complex, cutaway physical model of a Pratt & Whitney turboprop engine. From 2D plans and photographs, he created a 3D SolidWorks model, which he adjusted to create a better aesthetic for the model at reduced scale. This was used to help him decide which parts should be printed, using the Stratasys Objet24 printer at Arts University Bournemouth, and which should be hand-crafted.

“The SolidWorks model allowed me to see how the model would look before physically making it. This was particularly successful when making decisions for the internal fins,” says White.

The choice to use 3D printing to make these fins – the grey parts within the internal structure of the engine model – meant that the scooping ‘flick’ of each blade to direct air could be replicated.

jackwhitemodels.weebly.com

Super cool

The traditional British ice cream van is a sight we’ve been hard-wired to recognise from childhood, hence the appeal of Alex Brooker’s creation, made for a stop-motion animation film.

The brief for Alex Brooker’s ice cream van stated that the doors should open, the roof should be removable and the headlights should work

Among the requirements outlined in the brief were that the doors should open, the roof should be removable and the headlights should work. The rest was left up to Brooker’s imagination.

He began work by compiling a collage of classic cars and vans, before combining his ideas in a single sketch. He then worked with Rhino to bring a 3D model to life on screen.

The completed design was split into sectioned components in Rhino, in order to plot the CNC pathways and identify what cutting bits would be required.

Brooker created the model in chemiwood, painting the major sections with cellulose paint and adding exterior and interior details.

Finally, electronics for the headlights were inserted, laser-cut windows added and a full set of tyres applied. The tyres were moulded and cast from a single, 3D printed prototype.

“There’s no denying that 3D printing is having a huge impact on modelmaking – and my digital modelling abilities and ability to clean up 3D prints [are] frequently brought up in conversations now,” says Brooker.

abmodelmaking.com

Three exciting offerings from new modelmakers

Default