Without materials nothing exists. That is a fact. And certainly when it comes to developing new products, the same is true.

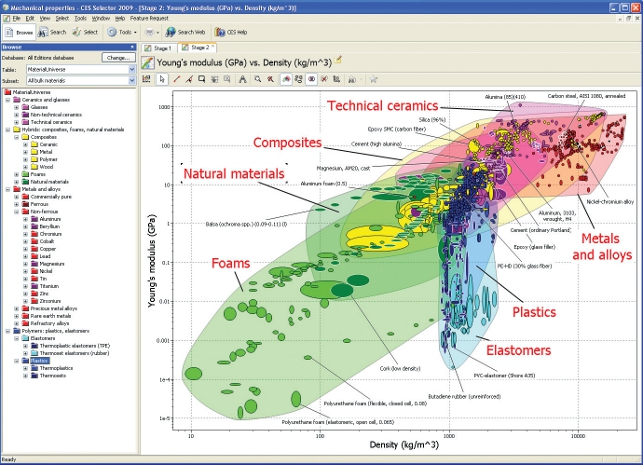

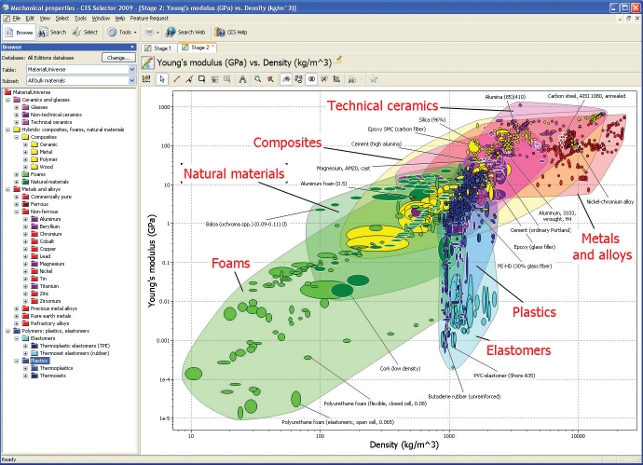

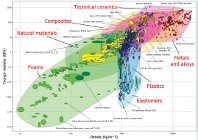

Granta Design’s CES Selector system allows the use of key material properties and performance indices to search and filter materials according to functional needs

But then consider the tools designers and engineers use on a daily basis, particularly the 3D centric systems we concentrate on in DEVELOP3D. Apart from a cursory assignment of material for visualisation purposes, massing studies and simulation, the study and selection of materials rarely gets a look in as part of the digital workflow.

Curious, don’t you think? Granta Design has been at the forefront of digital material selection techniques for over two decades now. For those that studied at one of the hundreds of universities that teach its methods, the names Mike Ashby and David Cebon will be legend. Part of the Cambridge University set, Ashby and Cebon developed a technique called Computer Aided Materials Selection.

This enabled the user to interrogate a database of materials using a combination of cross compared material properties and graphical display techniques, to find the correct material based on a set of selection criteria. Users can filter their selection based on these criteria and apply performance index methods to identify the optimal choice for specific combinations of design objectives.

This Cambridge Engineering Selector methodology (today embodied in the CES Selector software) has become standard fare for many engineering students and its charts will be familiar to many readers I’m sure. The CES Selector application framework soon took off and the pair looked to commercialise their work, founding Granta Design in 1994. Granta Design has since become a powerhouse in materials related technology.

The CES Selector tool broke away from its academic roots and has since grown as an application. The company has also built a reputation and technology that provides the ability to not only select materials, but also for organisations to manage increasingly complex in-house materials data.

The Granta Materials Information (Granta MI) platform provides tools that allow a whole host of different industries to collect their materials information together, rationalising and standardising it. The company is also establishing links with other technology providers in the design and engineering space. There are now live links between Granta MI and Dassault’s Abaqus as well as Pro/Engineer. And, of course, the recently announced project with Autodesk resulting in the Eco Materials Adviser.

Mainstreaming of materials selection

On my first visit to Granta Design’s headquarters in Cambridge in a decade, the burning question was why, after 20 years of educational success and deployment in all manner of aerospace and defence organisations, was the concept of digital materials selection not adopted amongst the mainstream? According to Dave Cebon, Granta’s managing director, the answer is complex. “It’s a lot to do with the users, the size of the company and the user profile,” he says.

“In education, it’s screaming along. It does very well in more innovative consultancies. It does less well in more mainstream engineering because there’s a lot of conservatism built into engineering and the risk averse processes in place. You don’t usually allow the average designer in an aerospace company free rein. You say, ‘This is a set of materials that you’re allowed to use.

They’re approved materials, we’ve already checked them out, we have the numbers, we know how they work. So you can choose from this short list’.” This situation is starting to change. Many organisations that have adopted Granta MI material information management system are now looking at adopting the concept of material selection but to their own inhouse data. “We’re now going full circle,” comments Cebon.

“What we’re finding is that our customers, who have previously been interested in managing that materials data, are now interested in our selection tools to put on top of their own in-house data and make the best decisions. That seems to be the main driver and within that context you get some other interesting dynamics happening within companies. We had one customer that came in and said ‘We spend $6 million a year on raw materials. We want to spend $4 million. Can you help us?’”

This customer had grown by acquisition and found itself with multiple divisions across the globe, each with their own materials specification, suppliers and preferences. Consolidating those discreet efforts into a centralised searchable database will afford them greater purchasing power during procurement and greater control over the whole process.

I was curious to know how this shift in Granta Design’s commercial business opposes the academic roots of CES Selector. “The whole thing has refined a lot,” says Cebon. “We started off with the world of materials and allowed users to select the optimal material from that full set. That’s perfect for education, but not for industry. Industry wants to make the right decisions but using a smaller set of materials.”

Sustainability focus

Of course, today more than ever, you can’t discuss materials without considering sustainability and eco-design. After all, much of the emphasis focuses on the materials used in the design and manufacture of products.

Whether that’s recyclability, the mandated removal of hazardous substances, removing material or switching material to develop ever more light-weight products. Materials are at the core of many sustainability projects.

Granta Design is no newcomer to the sustainability space. Mike Ashby has been working on extending the core materials database to capture environmental factors, not only of the materials but of their associated manufacturing processes too.

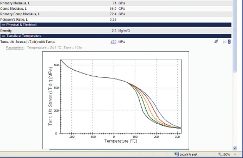

This has resulted in the Eco Audit Tool, built into the CES Selector system, which allows the user to consider the environmental impact of a product concept or iteration across the different phases of a product’s lifecycle – material production, manufacture, transport, use and disposal.

Unlike typical Life Cycle Assessment, these rapid calculations are performed in the early stages of design, allowing environmental impact factors to be integrated into the selection process. “ Mike Ashby ran a project in the university to build our first eco database and that would have been over ten years ago,” says Cebon.

“It was a long project and became the back bone of our eco data long before ‘ecostuff’ was fashionable.” I wondered how the focus on these eco tools had affected Granta Design’s day to day work. “An interesting thing was that the selection of materials to minimise environmental impact fits perfectly with our standard selection methodology,” says Cebon. “Normally what you’re trying to do is get some objective, whether that’s mass or cost, which you’re trying to minimise.”

“That’s your objective function. Sometimes, the best way to reduce the energy in your product is to reduce its mass. So, eco-selection doesn’t mean selecting the materials with the lowest embodied energy, it means selecting the material that gives you the lowest mass,” he adds.

However, there are some applications where the objective is embodied energy, such as civil engineering. “The Built Environment is interesting because the embodied energy is very high, but the use of phase energy is also very high and they trade off.

Whereas in an aircraft, you don’t care about the embodied energy because it’s all about the fuel consumption – that’s everything. The vehicle is burning kerosene for 20 hours a day, 356 days a year. That is its dominant primary impact and anything you can do to reduce it is critical,” explains Cebon.

“The thing about eco-selection is that it’s a direct extension of what we’ve been doing. First we do a selection for minimising mass or heat conduction and then we need to add the embodied energy issues and material process to get all of the different phases of the lifecycle.”

Final thoughts

Materials information and selection is an increasingly complex proposition. Take the use of composites. We now need a greater understanding of how materials perform.

Not only in a generic sense, but down to a manufacturing batch-level. This is something that’s becoming increasingly key in industries such as aerospace and defence.

It’s no longer enough to know the general performance characteristics of a composite. There’s a need to track the properties of that material, broken down by manufacturing batch for both the carbon fibre and the resin, often on a per part basis.

Alongside this, the world of compliance and materials legislation means that much of the design and engineering world is going to start dealing with materials information more routinely and to an incredible depth, down to the chemical composition or the CAS numbers of the chemicals used in a material’s production. Then there’s the push towards more sustainable design, which is about making intelligent choices and finding the most appropriate material for the given use case and geography.

When you combine all these factors, it’s clear that materials are really at the heart of what designers and engineers do. And what Granta Design has in its various product offerings, is a rich and unique set of tools that provide the user with insight into possible new materials, offering perhaps a different choice or a greater chance of innovation.

What I find most interesting is that these tools are finally starting to find their way into the 3D tools we use to define the products. It can only benefit everyone who uses them.

www.grantadesign.com

We visit growing materials information and selection specialists Granta Design