The worlds of technology, toys and video games are moving ever closer together. If a few years back it seemed absurd to suggest that a digital character could coexist alongside its physical counterpart, now, technology such as 3D printing is making it possible.

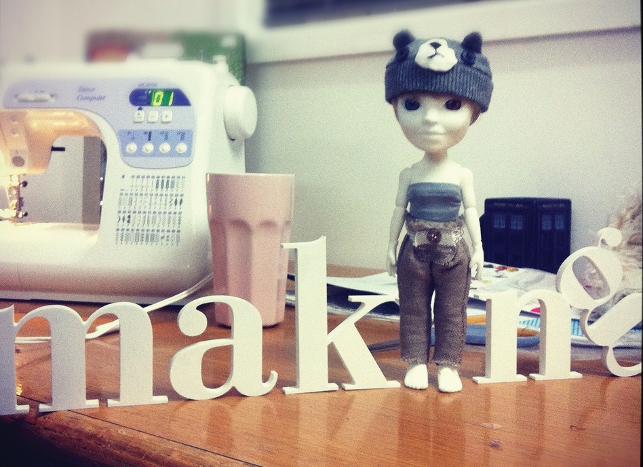

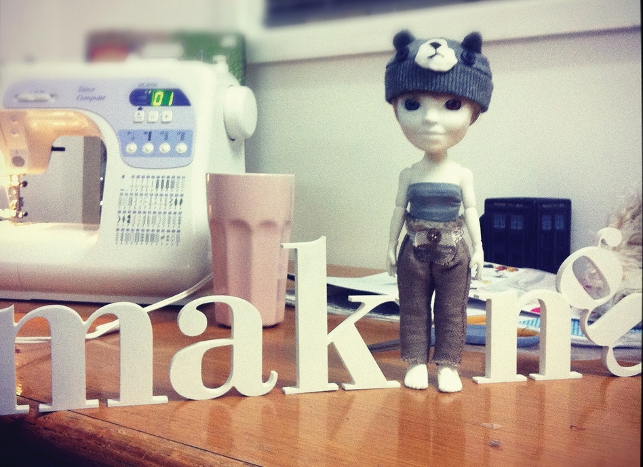

Makielab hosting a ‘Making Day’at the end of last year, inviting local makers to produce new outfits for the prototypes

In April, London start-up Makielab will be launching its first product – a 3D printed doll and associated app for customers to personalise both digitally and physically.

“We are a new toys and games company that is building games using the same 3D model pipeline to create on-screen avatars and also 3D dolls and action figures. So your avatar and doll are basically the same thing,” explains Makielab’s founder, Alice Taylor.

Taylor is no stranger to gaming having been involved in games on and off her whole life. She even experimented with building customisable avatars on the web 12 years ago and although technology and computing devices weren’t advanced enough at that stage to make it viable, the seed had been sown.

In her job roles since, first as the vice president of digital content for BBC Worldwide in Los Angeles and then as the commissioning editor at Channel 4 Education, she spent a great deal of time observing and working with young people who she realised all vary greatly in their tastes and explorations.

“This interests me a great deal and I knew that I wanted to do something next that looked at exploring identity and personality,” she explains.

A seed of an idea

The seed started to germinate when Taylor was struck by the lack of innovation and creativity she found whilst trawling the aisles of the London Toy Fair 2010.

“There is a slow march of innovation in toys, almost a begrudging innovation,” she remarks. “But then on the other hand you have the games industry which is fantastically open and innovating all the time.

In fact the past three years for games have been nothing short of extraordinary. Zynga – a social network game developer – just appeared out of nowhere, and recently got to nine million players for its Adventure World game in just five days.”

What she found at the Toy Fair also substantiated what she had recently read in the ‘The Real Toy Story: Inside the Ruthless Battle for Britain’s Youngest Consumers’ by Eric Clark.

As well as the ‘pink is for girls’ segmentation of many toys, which she abhors, she also saw evidence of the statistic quoted in the book that 95 per cent of the Western toy market is made in the Far East.

“As I was walking around it struck me how a lot of the booths were there to help visitors deal with China offering translation services, logistics services and so on,” says Taylor. “It also made me realise that the number of air and ship miles that toys come with is extraordinary. This bothers me and it inevitably has to change.”

Potential of 3D printing

An emerging technology that caused her seed to sprout was 3D printing and its potential to help reduce these air miles by enabling toys to be manufactured locally, if not by the individual themselves. Taylor experienced this at the Consumer Electronics Show 2010 where Makerbot Industries were printing Lego mini figures in the same ABS plastic used to make Lego.

So, she started exploring the different 3D printing techniques such as FDM, SLS and SLA and also the various service providers, including Shapeways and i.materialise, that print and then deliver 3D prints to the user’s front door.

“3D printing is really interesting because it means that you can manufacture your individual pieces locally. Other pros for me are that it’s a clean technology, bioplastics are coming and it has inbuilt recycling,” says Taylor.

So, she decided to pack in her “cushy job” in early 2011 to pursue her idea for a new kind of future-smashing toy – one that is customisable, 3D printed, locally made and game enabled. “I packed in the job and gave up the salary to sail off into the sunset waving a flag for 3D printed toys that talk to games,” smiles Taylor.

Of course, that may sound romantic but starting a company in a recession is anything but. “I was told that a recession is the best time to start up, if you can survive that you can survive anything,” says Taylor.

She then spent until June 2011 getting some equally passionate co-founders onboard, all bringing their own expertise and experience of game development, social media and global virtual worlds.

Competition winners

Although the four co-founders had a game plan, Makielab wouldn’t have been able to get off the starting block without funding.

This was a challenge and Taylor was putting a great deal of effort into fund pitching, which paid off when it became one of the ten companies to win the Technology Strategy Board’s Tech City Launchpad competition, which aimed at awarding R&D funding to digital projects in the East London area. The start-up was able to secure £100,000 funding, which was match funded.

Having officially launched at the end of June 2011, Makielab also set up a website with a blog to regularly update their progress as well as a twitter account. Unlike traditional toy companies where everything is shrouded in secrecy, they planned to be as open as possible.

This also goes for the dolls themselves, which will be released under a Creative Commons License. “Generally, the ethos is to try do it locally, try do it carefully and with love but always open it up. So

everything we make we’ll release the patterns so people can play and poke about with it,” says Taylor.

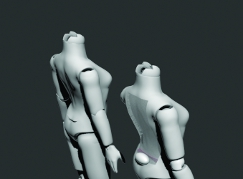

For the next few months Makielab continued with the R&D and model wrangling working on skin colour, eyelashes, eyebrows, better articulation and joints.

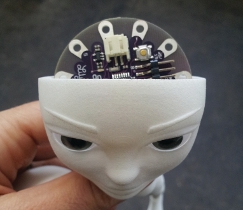

Luke Petre, one of the four co-founders and chief technology officer, was also looking at how to get the physical doll to talk back to the online world in a loop and was working on something called ‘data-freckles’. “So you paint a pattern on the doll’s face which is designed to connect with an online version in-game world.

Essentially these data freckles on the doll act as an organic QR code so you can start using location based stuff plus patent recognition for doll identity,” explains Taylor.

The dolls are designed using a combination of SolidWorks and Autodesk 3ds Max. “Our engineer works in SolidWorks cutting up the mechanical joints and our artist then slips them into 3ds Max,” describes Taylor. “They are a polygon soup at that point and although in microscopic layers it’s probably a bit rough and ready, it doesn’t really matter because it works.”

“This process does involve a bit of back and forth between the two because some of the sizing does lose its CAD level of accuracy but once you’ve got it, you’ve got it. However, I’m sure it will cause pure CAD people to get hairs on the back of their neck looking at the way we do it,” laughs Taylor.

Taylor also spent time becoming more versed in 3D printing by talking to EOS, a German supplier of laser sintering 3D printers, and actually visiting i.materialise in Belgium who undertook Makielab’s first set of prints.

As well as their own personal Makerbot to create prints in-house, Makielab also had 3D prints done by a number of local rapid prototyping service providers including London-based Digits 2 Widgets and Newbury-based 3T RPD. “We are going to be using these bureaux effectively as a distributed manufacturing network who will supply us with the basic printed body parts.

From there we will add finishing, painting, boxing and the whole digital side of the product,” explains Taylor.

Highs and lows

Although Taylor admits to being taken in by the 3D printers when visiting i.materialise – “they were all in the service room humming away like ‘daleks’” – she realises there are challenges to using this manufacturing technique too – the biggest being material.

Although having selected to use SLS (selective laser sintering), the standard white nylon used in this process isn’t as smooth as they would like.

“Although SLS provides lovely detail our biggest challenges with it is that its bone white, goes yellow over time, gets grubby and is porous. But I know that these things are getting better and will change over time,” says Taylor.

Another downside to 3D printing is that it’s not as fast, efficient and cheap as globalised bulk production. Although Makielab will do its utmost to ensure that its products remain affordable, it will no doubt cost more than your average plastic doll, but then it isn’t an average plastic doll.

According to Taylor, they’ve been advised that a toy sold at Christmas shouldn’t cost more than $100. “This is where it gets really interesting because that is received wisdom from a mass manufacturer, a mass marketeer and a mass retailer.

But what we’re doing has no mass marketing, no mass manufacturing and frankly no mass retail. So it may be that all sorts of things are different.

For instance, how much is somebody willing to spend on a product they’ve had a hand in making? Will they look after it more and throw it away less? Anecdotally the answers are all yes but who knows?” questions Taylor.

However, a major upside of using 3D printing is that they won’t have the huge ramp up times of traditional toys. It is not uncommon for a toy to take four years to go from the concept stage, through production, shipping and finally to market. Whereas with 3D printing, the consumer can upload their prototype one day and receive a physical product the next.

“So if someone, say Lady Gaga, has decided to put two demon horns on her forehead, we can replicate that the next day. That kind of rapid response to what’s on TV Saturday night is amazing because the traditional toy industry can’t really do that,” says Taylor.

“Or maybe the user wants their doll to have a little beauty spot in a certain place, or to have their name printed on the inside or even if they wanted it to have centaur feet – they can.”

Been there done that

However, despite the majority of the doll being 3D printed, with accessories such as the eyes, hair and clothes being produced elsewhere, at the end of the day Makielab are still manufacturers and still have the production and logistical challenges that all manufacturers face.

However, Taylor is not too perturbed about these as they aren’t new challenges, they’ve all been dealt with and solved before. “We’ll have the usual challenges of supply vs demand as well as shipping and production time constraints.

I am also fully aware that logistics can be a nightmare but they’re a logistical nightmare not a technical one. A lot of this can be mitigated with software. So as long as we’ve got an incredibly robust and extensive customer ID system, the identity of each part and its matching parts can be built into the product,” says Taylor.

The intention is that the doll will be ‘naked’ in the sense that customers can paint and modify inline with their on-screen avatar. With the clothes, although the intention is for customers to inject their own personalities into their dolls by making their own clothes, the launch product will come with a series of outfits that have all been made using local makers in London.

“The plan is that we’ll release the doll’s vital statistics and supply a pattern book to encourage customers to make their own stuff. They could also use secondary local production by sending it to the makers at Etsy [an e-commerce website focused on handmade items] or similar,” says Taylor.

Of course a vital part of any new product development process is user testing. This helps to ensure that you are on the right track with any suggestions being fed back into the design. So towards the end of last year Makielab hosted two events and invited a range of kids, teens and adults to play and experiment with a selection of games and avatar customisation prototypes.

Although young people were invited to those events, the launch product will be specifically aimed at adults. “We don’t want kids to have to suffer for any reason. Adults are fine, we can torture them,”jokes Taylor.

“So for our first customer we are basically going for forgiving, interested ‘nerdom’. Essentially we’re reaching out to those enthusiasts that want to experiment and play.”

Time to play

Another challenge that Makielab face is making consumers aware of what they are doing especially as they don’t have the enormous marketing budget – or any marketing budget really – that toy companies do.

However, Taylor is hoping that all the current noise around 3D printing will prove beneficial. “There is no doubt that the potential of 3D printing technology is startling and the good thing about all this hype is that it certainly helps to get people’s attention and attention is something that is really hard to get these days,” says Taylor.

So, following a whirlwind year that has involved launching a new company, finding co-founders, researching, prototyping, modelling, testing, tinkering, playing, hiring more people, doing ongoing investment pitching and moving offices, Makielab’s first product – Makies – will be ready for launch in April.

It will essentially be a DIY doll and action figure builder. “The point about doing the open Alpha in April is that there’s a strong argument that this is a very unusual product and people won’t know what to do. We can’t predict either what they are going to do so we’ll see what happens,” says Taylor.

However, she does know that they are onto a good thing and have exciting plans for future development. “From the Makies launch we’ll begin to release a series of digital and physical goods – apps, games, objects, clothes – that build out Makies into something never quite seen before,” concludes a rather coy Taylor.

Alice Taylor will be talking at DEVELOP3D Live about the challenges of building a groundbreaking business centred on customisation and 3D printing. Make sure to come along on 20th March to see her in person.

A start up that’s causing a bit of a stir in 3D printing and mass customisation

Default