Your additive design might be full of spice, but could it give your customer tummy trouble? Our columnist SJ writes on the importance of striking the right balance between creative flair and customer comfort

It would appear that I’ve grown a second head, sprouted horns and am covered in green scales, for all the open-mouthed gawking my customer is doing. I glance at the computer screen, filled from end to end with my DfAM work. It’s a dramatic swirl of topology optimised structures, supported by lattices that look nothing like conventional block supports. I swallow hard, feeling my imposter syndrome closing in, and ask: “What do you think?”

He hesitates, his face paling. “Well… you’re the expert, SJ. It’s all up to you.” He chokes out the last part, sounding like he might really be sick. “Just looking at it… it doesn’t sit right with me. How do you know it’s going to work? Have you… ever… printed anything like this before?”

Now, I imagine him clutching his stomach to fight off the reaction he’s having to my design. A design he’s clearly not finding easy to swallow.

Oftentimes in AM, we’re pushing the very limits of design to explore new frontiers in terms of materials, performance, even the physics of the build chamber itself. Topology optimisation and generative design allow me to create the most efficient, shape-optimised, lightweight designs.

So, if it’s a shape that wasn’t even manufacturable until this young technology came along, I can’t say with confidence that I know it’s going to work. I could easily tell I was not passing this engineer’s gut check. I see beautiful internal lattice structures – but the customer sees high risk, high costs, a potential need for redesign, and a slipping schedule. So, how do I win over my customer’s stomach (and his confidence) with my rather spicy style of design?

Additive design – tummy medicine

Additive is a disruptive technology. You see the slogan (annoyingly) stickered everywhere on LinkedIn, plastered over webinar screenshots, and slapped on the swelling tide of pamphlets in the mail from businesses looking to “fill your supply chain needs.”

Disruptive is definitely a good way to describe the effect that additive has on the experienced bowels of veteran engineers.

I’ve done DfAM for aerospace engineers who worked during the time of the Challenger mission and were still haunted by the literal life-and-death lessons learned. It’s no surprise they’re hesitant to adopt a technology that could produce a rocket in three months rather than three years.

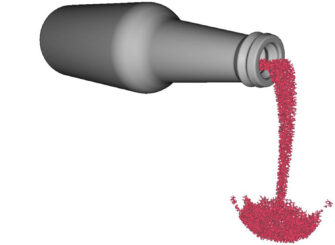

Everything in AM is new and foreign and outside of their regular routine, their comfort zone. I sense excitement in these engineers, but also fear. Topology optimisation is the spicy seasoning to additive design. The Sriracha sauce, if you will.

But as much as I love my build plate with a bit of a kick to it, it won’t mean anything if it gives my customer a massive case of indigestion.

I see the damage a lack of widespread education has on additive’s acceptance into organisations. There’s typically a push from young, hungry, go-getter engineers entering the workforce and another push from additive champions at the top of the organisational food chain.

This creates an uncomfortable pressure on those in the middle, who have spent their entire careers creating parts by conventional means. They already have their superpower, their own secret sauce, and they don’t want to give that up to a technology that’s new, untried, and untested.

I return to my desk, pull up my design, and start ticking through my redesign checklist. I put myself in the customer’s chair and try to see things from their perspective.

Is part function still inherently obvious? Does the design make sense in terms of manufacturability? Did I add recognisable datums to the part for postmachining and clean-up? Is the powder escape plan functional?

I pause at the last question on the list: Have I successfully conveyed the constraints of metal printing to the customer and how I’ve addressed those constraints in each modification to the original design?

I definitely thought I did – but maybe I could have done it better?

Finally, relief

When I next met my customer, he relaxed a bit as he began to see shapes and features that he was more familiar with. For this second round, I pulled back on the optimisation feature, striking a balance between optimised design, the original part, and manufacturability.

With his confidence growing, I explained the design changes I’d made and why each one was necessary to the AM process.

Afterwards, he understood well enough to make his own design suggestions. Providing input and assistance – collaborating on the recipe together – brought down his unease. And I got the green light that this mildly spiced plate would pass with flying colors. Cue the outro music.

As additive adoption grows and new design flavours present themselves, it’s easy to get carried away with the seasoning. Heavy spices like topology optimisation enable limitless complexity and bespoke workflows. The complicated umami of generative design provides an entire deck of solutions – all at once – letting us choose based on any number of factors, be it budget, material consumption, or performance.

Advances in software present designers with unlimited options, but we mustn’t forget the plate we are making isn’t for us – it’s for our customers (and their sensitive stomachs). Additive design is about more than who can pack the most flavour onto a plate. It’s about having highly satisfied customers who remember their initial taste, how it made them feel, and would want to do it again.