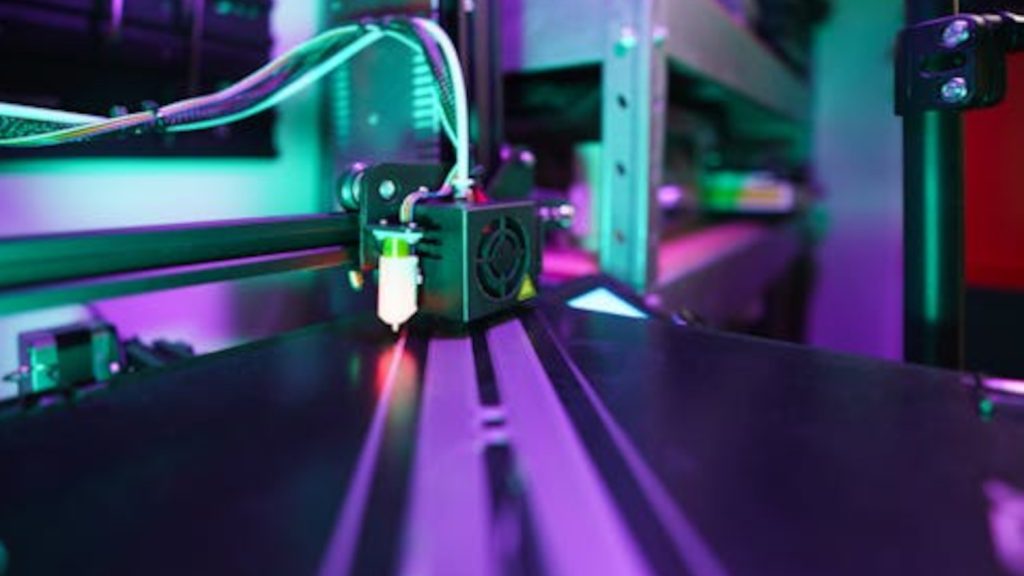

Beam shaping laser technology in 3D printing has much to recommend it, writes columnist SJ, but it complicates how we test samples and we’re probably going to need better software to keep track

Growing up as a small child in a Caribbean household that had more people in it than seats at the dining table, the kitchen was the epicenter of the home in which my large, extended family gathered.

It’s been a long time since I’ve been home and longer still since I’ve tasted traditionally made coconut breads, but I still remember the clouds of flour in the air and my infinite curiosity as I asked my grandmother how we made bread without a recipe card. She would always say to mix the ingredients until it “feels right” or to bake the bread “until it tells you it’s ready”.

I must have spent hours in front of her oven, watching and waiting with a furrow in my brows.

Fast forward 25 years and I’m spending hours in front of a laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) window, watching once again, with a furrow in my brows, and still unable to tell if what I’m baking is ready.

Stirring the pot

In my opinion, laser powder bed fusion (LPBF) isn’t an expensive process. However, the material testing, validation cycles, the building of material allowables, databases and the like – that’s expensive.

One reason is the abundance of samples requiring testing. For example, to build a statistically significant data set for Metallic Materials Properties Development and Standardization (MMPDS), you need at least 100 samples. Of those 100 samples, at least 10 have to come from different lots/heats to establish reliable A-basis and B-basis allowables. For those unfamiliar with the LPBF “oven”, that’s like saying you need to bake 100 loaves of bread with the same brand of flour, but the loaves need to come from at least 10 different ovens.

For those who spent their time during the Covid pandemic perfecting sourdough, that may not sound too intimidating. But for LPBF, we often have to develop the cooking process as well – a complicated design of experiments where we have the ability to alter over 100 processing parameters until we achieve something that “feels right”.

When beam shaping technology hit its first powder bed, our efforts to produce ‘loaves’ that are fluffy on the inside and perfectly crispy on the outside suddenly seemed in peril

Some parameter sets are great for lasing bulk material. Others are optimised for specific features like thin walls, lattices or overhangs. And for each parameter set you use, for each variation in the process – be that laser speed, laser power, layer thickness, hatch distance or scanning strategy – you have to qualify material for that specific set. In short, there’s a lot going on in our kitchen, but I don’t mean to overwhelm you. Many of these parameter sets are well established, especially those supported as defaults by AM machine manufacturers. But in 2025, when beam shaping technology hit its first powder bed, our efforts to produce ‘loaves’ that are fluffy on the inside and perfectly crispy on the outside suddenly seemed in peril.

Frying pan to fire

Most of the research, development and qualification of LPBF and its subsequent parameter sets has been achieved using a standard Gaussian laser beam – a single, focused point of high-intensity energy (anywhere from 500W and 1kW).

But the new beam shaping lasers – or ‘doughnut lasers’ – work differently, spreading energy across a central spot and outer ring. Dynamic beam shaping offers six indices where you can start at the standard Gaussian beam and change the shape of the ‘doughnut’ in the blink of an eye, allowing you to switch quickly from lasing bulk material to fine features. The result is better throughput, higher productivity gains and (theoretically) faster print times, which should drive down per-part costs.

But if I have six indices and multiple parameters per index, does that mean I need 100 samples from 10 different machines for each index for a total of 600 samples minimum?

As an industry, we’re still arguing over the proper qualification path for multilaser systems. How will we ever come to a consensus when it’s now 12 laser systems with each laser having six different indices? The complexity of this problem simply isn’t discussed enough.

I’m concerned that beam shaping will set back manufacturing readiness levels and the perception of technological maturity. I also feel that it could have drastic impacts on qualification frameworks. Does currently available software even support assigning and managing all those new parameters within the print file? And if not, what AI/ ML-powered software will we need to better understand and qualify these build files?

(Thinking about this, if a software evolution brings about the death of the .stl file and the rise of the implicit, then you can count me as being all-in on beam shaping.)

For now, however, the worries keep multiplying as quickly as the parameter sets. The furrow in my brow is as deep as the Grand Canyon.

One thing remains the same: I just want to bake good bread. In other words, I want to make parts using robust, reliable and repeatable processes. Whichever laser produces the best ‘bread’, then I’m all for it.

This article first appeared in DEVELOP3D Magazine

DEVELOP3D is a publication dedicated to product design + development, from concept to manufacture and the technologies behind it all.

To receive the physical publication or digital issue free, as well as exclusive news and offers, subscribe to DEVELOP3D Magazine here