BOA Technology’s innovative ratcheting mechanism gives footwear a precise, secure and comfortable fit, and this tough technology relies on a design process that is as agile and demanding as its end customers, as Stephen Holmes discovers

From its origins on the ski slopes of Colorado, the popularity of BOA Technology’s micro-adjustable fastener system has flourished over the past two-plus decades. Today, it frees athletes of many kinds from the struggles associated with shoelaces. They include track stars and trail runners, road bike racers and mountain climbers, fishing fans and golf enthusiasts.

When speed is of the essence, or gloves get in the way of manual dexterity, the BOA Fit System replaces traditional shoelaces with a system of dials and cables that give footwear a more precise, secure and easily adjustable fit. The innovative system been used in work boots, too, as well as in medical bracing.

The system’s core design, meanwhile, has gone through several phases since its debut as a fastener for snowboard boots back in 2001. It has been pared back for lower power applications, such as low-cut athletic footwear, and beefed up for use in more extreme environments. It has also been reconfigured for use in different apparel categories, including bike helmets and fishing gloves.

For the BOA Technology design team, there’s huge value in understanding different end uses and in bringing specific needs into the iteration loop, according to director of engineering Clay Corbett.

“It’s not just making a little ratcheting mechanism,” he explains. “It’s also [figuring out] how you make it perform when it’s packed with dirt and sand, or when it’s working at really high tensions, like in an alpine ski boot.

The team is now in a phase in which it’s primarily focused on introducing further innovation in categories where the BOA Fit System is already well-established, he continues.

“We’re doing that by asking, ‘How do we make things more integrated? How do we improve the user experience with the product? How do we make it more sustainable and use less plastic along the way?’”

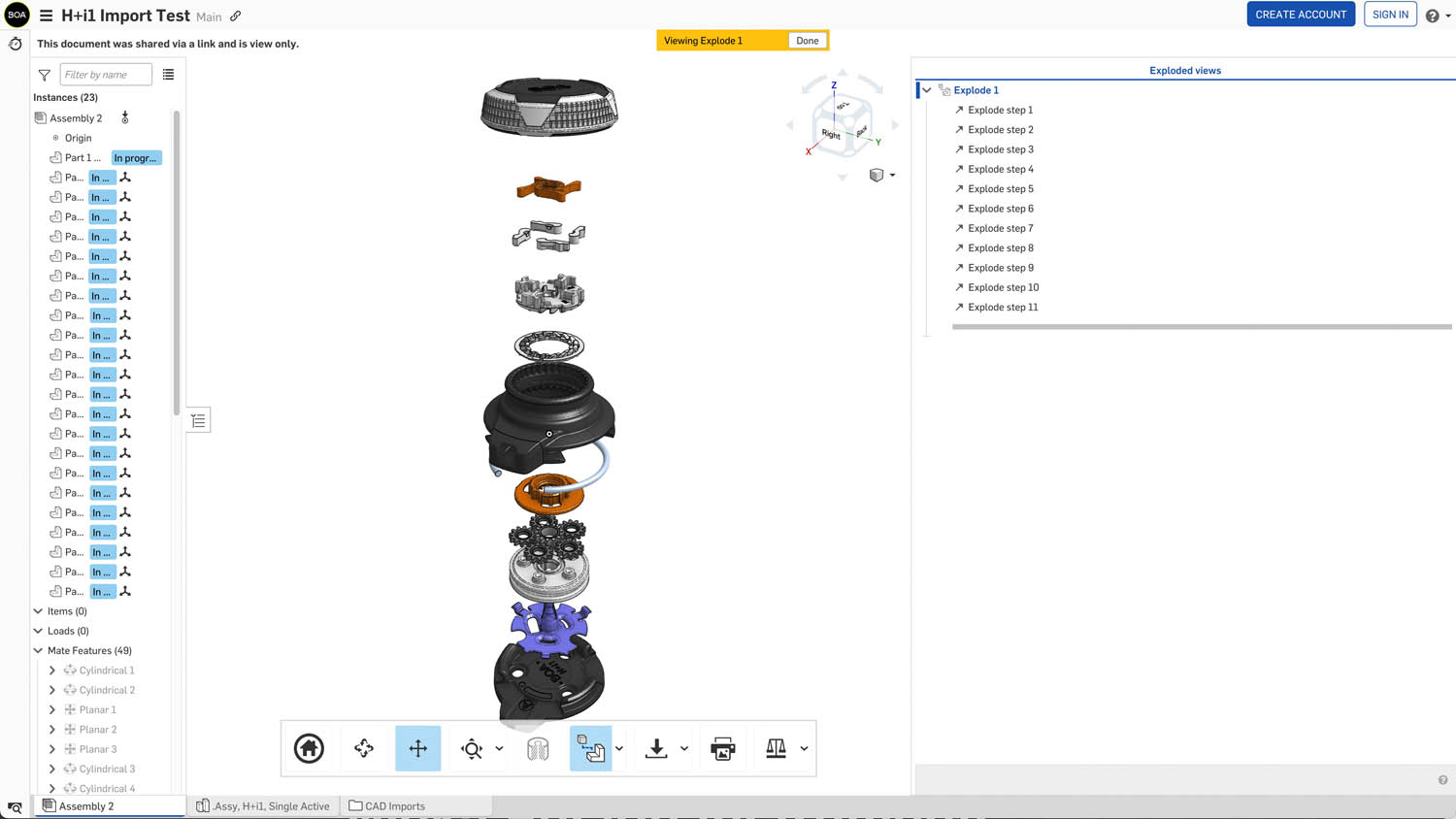

This requires intensive design and engineering activity. Take, for example, BOA Technology’s most recent design for an alpine ski boot fastener; its development forced the team to consider punishing levels of forces and tensions, while simultaneously maintaining the familiarity and simplicity of its user interface. In response, the company developed a compact new planetary gear system within the ruggedised device housing and designed new wire guides to better fasten the boot.

Much of this work, says Corbett, depends on members of the team taking their current experience with the system and applying it in entirely new ways, leaning on the latest technologies to help them build and test their ideas as quickly as possible.

Get dialled in

BOA Technology designs and engineers the whole Fit System in-house: the iconic dial and its internal gearing; the textile or stainless-steel cables that provide the lacing; and the low-friction guides that replace traditional shoe eyelets.

But developing each individual product is far more than simply attaching a standardised system to a shoe, Corbett emphasises. When you see a BOA product on a piece of footwear, he points out, it’s been designed to work specifically with that piece of footwear.

As a supplier to some of the world’s largest sports and outdoors brands – including Adidas, Fizik, Timberland, Salomon and Fox Racing – the choice and placement of BOA Fit System components is critical to performance and often leads to entirely new designs.

At present, BOA has developed ratchet and lacing systems for four power levels: low, mid, high, and a more extreme level such as is seen in alpine ski boots. These levels enable the company not only to deliver the necessary degree of lace tension but also vary the size of components and how the system looks when fitted to a particular product.

A lot of work goes into creating a configuration that is super-low friction and creates an even pressure that comfortably closes the fastening, Corbett explains, pointing out that running a cable system through the tight bends of existing shoe eyelets simply wouldn’t achieve this goal.

Much of the guidance on where best to position the system comes from BOA’s in-house biomechanics lab, where designers and engineers validate configurations and different fits. This brings a great deal of practical insight to the process as well as highlighting potential benefits of different approaches.

At the same time, the company works closely with its partner brands from the outset. In fact, while the product development team focuses on developing new products, an application team works directly with these footwear companies and their designers and factories in order to ensure that everything is installed correctly.

Making a switch

For much of its history, employees at BOA Technology have relied on 3D CAD as the place where design work starts. In the past, they used Dassault Systèmes’ Solidworks to model and test CAD models. More recently, they have switched to PTC Onshape. The shift didn’t happen before some thorough evaluations were carried out to determine whether the Onshape feature set was a good fit for BOA’s demanding design process. Having seen that it was, the team began to explore some of the benefits they might experience from a cloud-native CAD system like Onshape.

“One thing that was really great was just some of the branching and merging stuff within the data management, just so that our team could really experiment a bit more along the way,” says Corbett.

“It made it a lot easier for people to just try out ideas, get things down, merge things back in if they made sense, or just leave them if they didn’t. I think the overhead in the traditional PDM system of doing that kind of stuff prevented a lot of it from ever really happening.”

Having previously worked as an applications engineer at a Solidworks reseller, Corbett knew that system inside-out, but says he was impressed by what Onshape was able to offer. “I think the big benefits we saw when looking at Onshape were, first of all, just the stability. Everyone can fire it up and start working, and we don’t have to worry about so many of the hardware issues or software crashing,” he says.

“Working with Solidworks all those years, I had to learn a lot about how Windows works under the hood and stuff like that. That’s not really doing CAD work! That was a really big issue for us, and we were at a spot where it was getting difficult.”

The ability to more easily collaborate on CAD models and across PDM is another benefit. Previously, BOA stored everything in a PDM vault that all the design and engineering team needed to access. But accessing this via a VPN proved troublesome for off -site staff and there were further challenges around checking files in and out. “If someone goes on vacation and forgets to check something back in, that kind of thing [can be problematic],” says Corbett, grimacing at the recollection.

For the most part, the product development team is based in the same office. “They can just yell back and forth with each other and walk across the room,” laughs Corbett. But with a growing group, and members of the brand-facing applications team scattered around the globe, BOA Technology is starting to see more collaboration using the CAD software’s features, like sending Onshape links back and forth.

Including the knowledge of the applications team – many of them experts in pattern cutting and shoe construction – increases the potential for the product team to design better products. Already, a set of rules has been developed to help designers understand the shoe manufacturing process: what processes a shoe will need to go through, the dimensions it will need to fit, the type of sewing used to apply the BOA Fit System to a shoe. While BOA products are designed to be tough in the great outdoors, says Corbett, the manufacturing process “is another demanding environment that our products need to be able to survive.”

Testing times

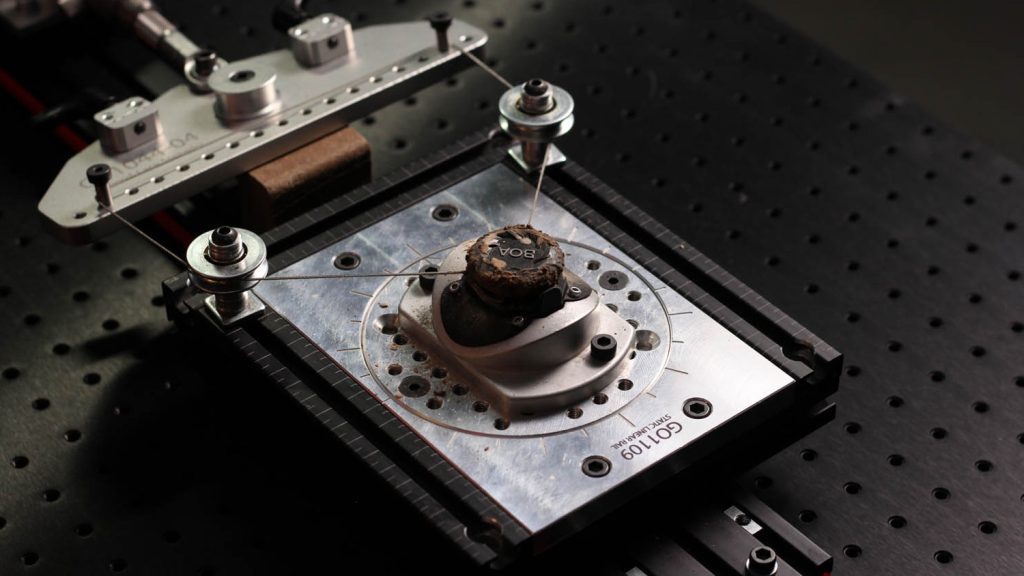

Heavy testing of BOA’s products has been critical from the very early days of the company. In fact, methods have evolved only slightly from the early ‘make it to break it’ trips performed on the ski slopes of the Rocky Mountains.

While the team runs CAD models through a handful of FEA simulations, these typically act as a ‘gut check’ to make sure a design makes sense before heading to physical prototyping. All results from physical testing are looped back into the FEA model to check it correlates as a design progresses.

But it’s physical testing that plays a more critical role, with BOA’s well-stocked workshop offering a range of 3D printers and CNC machines to build prototypes.

As Corbett explains: “We use the right prototyping process for the stage of the prototype that we’re in. We’ve got some 3D printers that are fast and easy to use, that’ll just give us a good gut feel on size, whether something looks about right integration-wise, and on basic function.”

From there, the process becomes more specific, edging closer to identifying what the ideal production material and product performance should look like, and narrowing these down with each iteration.

The goal, Corbett explains, is to establish a test loop that is as specific as possible for a particular product. To do this, BOA builds tests to mimic the environments where the product will have to perform under the toughest conditions.

Many prototypes are built using 3D printers from 3D Systems, including its Figure Four and MultiJet Printing (MJP) technologies, which use resins to create high-resolution, plastic parts.

The MJP technology is used heavily for fast iteration, says Corbett. While parts produced in this way are not quite as durable for testing, this technology is fast and easy to use when members of the design team want to move fast and print a few rounds of prototypes within a day.

The Figure 4 technology, meanwhile, supports wider material options, including Figure 4 PRO-BLK 10 – a tough, rigid plastic. This makes the technology perfect for more functional prototypes that give an accurate idea of how a part will sit on a garment.

This aspect of testing requires dials to be sewn directly into fabric without moulded holes. Finding conventional plastics that can be stitched is hard enough, let alone finding a UV-cured 3D-printed material that will perform without cracking.

Getting prototypes onto the shoe for early testing and interaction is a big plus point for BOA’s design team, even for concepts that don’t make it to production.

Putting iterations through real-world use and abuse helps designers gather more design and performance data that provides firm indications of what works and what doesn’t.

For final test models, BOA uses CNC-machined prototypes to get as close as possible to the materials used in the end part, giving team members a chance to send products out to the test lab where they’re subjected to load and tensile tests, and into the hands of almost 350 field testers out in the real world.

“We have a pretty robust field-testing program with the real diehards who are out every day on this gear – people who are putting in over 100 days a year on skis or similar,” says Corbett.

“And then, honestly, for the catch-all, sometimes we just take things out to the parking lot and kick it against the brick, really hard,” he laughs. “That helps us find really unexpected stuff!”

Always firmly in mind is the fact that BOA Technology’s products are used to fasten critical gear, with significant implications for sporting results or even the health and safety of the wearer. Conquering the unexpected is part and parcel of what the product development team does. By combining cutting edge technology with good old-fashioned brute force, BOA Technology ensures that its products remain dialled-in, regardless of punishing usage and harsh external conditions.