In partnership since 2017, McLaren and Stratasys have been working on 3D printing test and end-use parts to speed up production times and improve performance. To date, the legendary British Formula 1 team says it now 3D prints 9,000 parts a year

Production times for Formula One vehicles are becoming tighter and tighter and so is the budget available to motor racing teams. When time and money are short, adopting AM can be a convenient choice for designers and manufacturers.

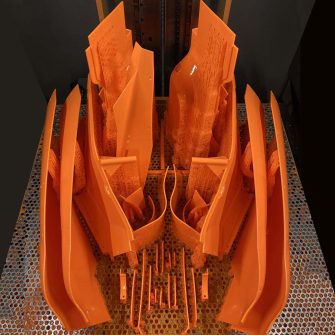

McLaren Racing is responding to time and budget limitations by 3D printing thousands of parts with large next-generation Neo 800 stereolithography 3D printers from Stratasys.

McLaren is producing 9,000 parts per year across numerous front and rear wing programs, as well as large parts of the side bodywork and top-body. The team reports that part production time has been dramatically reduced: certain large parts like scale model top-bodies can now be produced in as little as three days.

It’s also less expensive, says McLaren Racing. It allows the team not only to save money but to meet new the regulations on budget imposed by the Fédération Internationale de l’Automobile (FIA). With the sport facing uncertain times and no income coming in during Covid, the FIA decided to bring the budget cap down from £151 million to £125 million for its first year of operation in 2021, then down to £121 million for 2022, and £117 million in 2023.

At its base in Woking, UK, McLaren can now manufacture all aerodynamic parts using its in-house printers which saves costs on subcontractors and the associated quality assurance QA process. The team says it can also 3D print jigs and templates, and small moulds that would have previously been machined from metal billets.

Not only does the speed of Stratasys Neo800 stereolithography process save considerable time, says McLaren, but it also saves on more costly metal material by not wasting large amounts of waste in the form of swarf removed from machining.

Lower cost, better results

Beyond saving time and money, the team has reported that the new 3D printed parts seem to provide improved aerodynamics during wind tunnel testing due to the higher accuracy of the parts printed in its five Neo800 systems.

“Stereolithography technology and the materials have evolved, changing the way we use it,” explains McLaren head of AM Tim Chapman. “We do not just manufacture prototypes anymore; we now produce many full-scale components and full-size tooling.”

For wind tunnel testing, the team uses 60% scale models to optimise the aerodynamic package and provide more downforce and balance for the front and rear loads on the car.

“Wind tunnel testing is still the gold standard when assessing how every surface works together, either as an assembly or as a complete car,” explains Chapman. “Our Neo series of 3D printers have helped us to dramatically reduce the lead times.”

The right material for the right technology

The resin material selected by the team is Somos, patented by Covestro – itself recently acquired by Stratasys.

The material was developed specifically for wind tunnel models with the end parts looking to be strong and stiff, while being speedy to post process.

“We find the high-definition components from our Neo machines require minimal hand finishing, which allows much faster throughput to the wind tunnel,” continues Chapman. “In addition to speed, we can now produce wind tunnel parts with supreme accuracy, detail and surface finish, which has enabled our team to enhance testing and find innovative new ideas to improve performance.

“I cannot overstate how important these benefits are in Formula One, with super tight deadlines to deliver cars to the next race, and where the smallest design iteration can make all the difference between winning, losing or making up positions on the grid.”

This is exemplified by the 50 or 60 air pressure housings embedded within McLaren’s race cars to enable air pressure readings across various surfaces: the small pressure tapping running through these components is highly intricate and detailed and sit within the car throughout testing and races to allow engineers to continuously monitor and optimise aerodynamic performance.