Donkervoort has a reputation for pushing engineering to the limits in its designs, and its upcoming supercar is no exception, featuring parts more associated with Formula 1 than the public highway, as Stephen Holmes learns

Donkervoort is a Dutch company that prides itself on combining low-volume luxury with exceptional performance, a skill that has seen it achieve world acceleration records and leading Nürburgring lap times.

For the company’s upcoming P24 RS model, which promises to offer the marque’s most extreme performance yet, Donkervoort’s 50 specialist staff have been working closely with suppliers to develop high-performing, super-lightweight components and systems.

The P24 RS also features the first engine developed in-house by Donkervoort, with customer turbochargers built by F1 suppliers Van der Lee. These require a constant supply of the coolest air possible, which is why water charger air coolers (WCACs) were chosen for the P24 RS. Water is cooled through an external radiator and then redirected to chill the intake air before it enters the combustion chamber. The precision with which this happens enables the consistent, high performance delivery expected of a F1 powertrain.

However, Donkervoort soon found that no existing design would fit inside the compact layout of the P24 RS engine bay, so it turned to Conflux, an expert in building heat exchangers using highly optimised 3D printed designs.

After consulting with the car’s engineers, who provided the boundary conditions for the needed parts, along with their desirable requirements and attributes, Conflux shifted from a single- to a dual-WCAC solution.

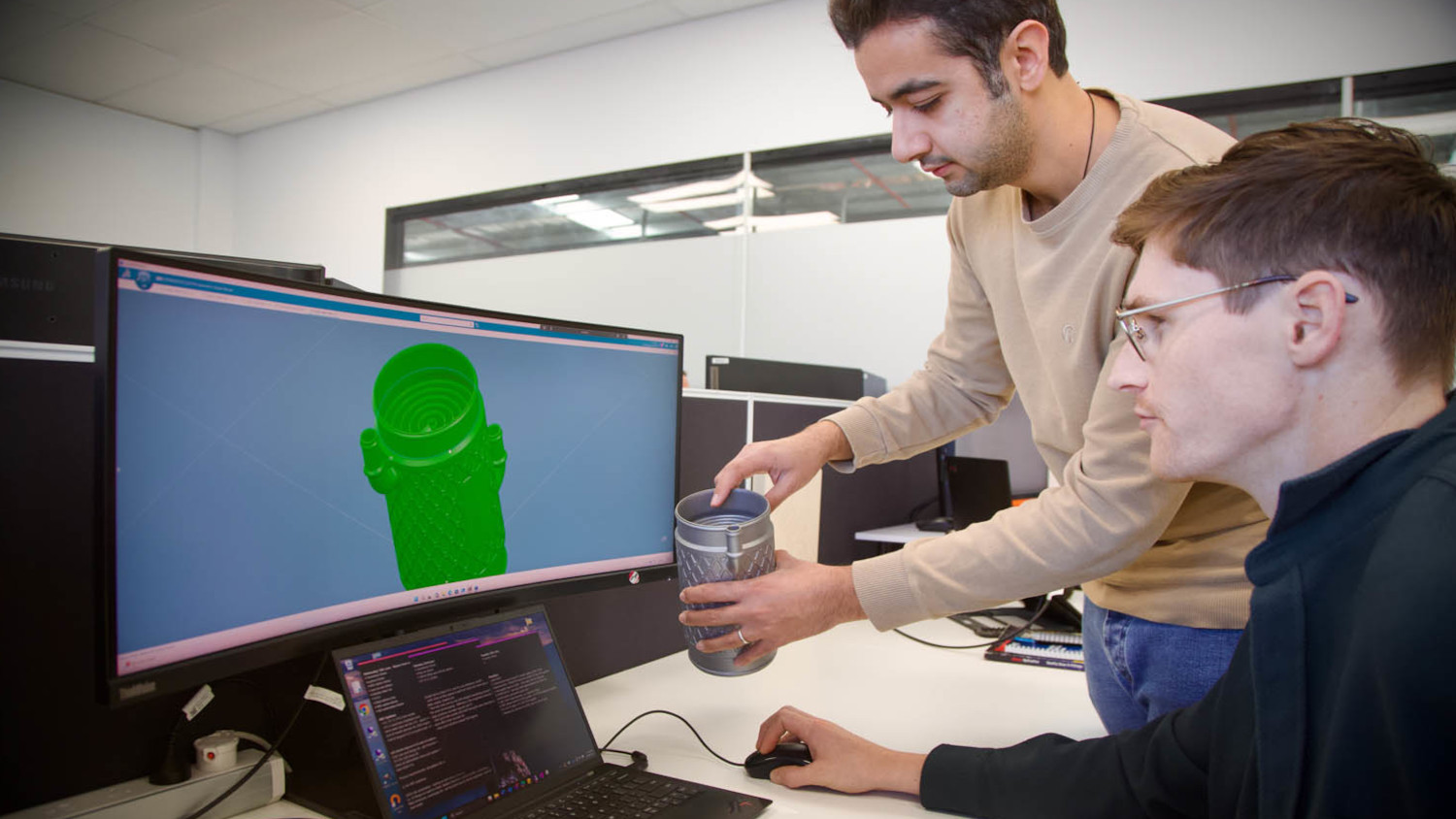

To build the 3D CAD models for the package, its inlets, outlets and heat exchanger design, Conflux’s designers used Dassault Systèmes Catia, before meshing the model to perform in-depth CFD analysis to hone the performance.

Keeping cool

Creating a custom WCAC solution for Donkervoort followed the same pathway as creating any other heat exchanger design, explains Dijon Valentim, engineering manager at Conflux. The crucial questions to ask:

What’s going into the part and what’s going out? What coolant or media are you feeding into it? What condition do you want those media to be in when they exit?

This workflow was handled by Ansys Fluent, along with tools developed in-house that help reduce simulation turnaround time. In addition, the Conflux team leant on its vast libraries of heat exchanger cores that have already bench-marked performance characteristics.

“Simulating is one thing, characterising actual performance is another thing – and the correlation between those is really what helps drive efficiency and drive efficacy of solutions,” says Valentim. “There are a lot of funky things going on in heat exchanges, a lot of physics is happening, and to be able to correlate back to your simulation and have a very high confidence level is what helps us to push the envelope further and further.”

Conflux’s engineers were able to make changes that ensured the design met customer performance targets around pressure drop, weight reduction and heat exchange performance. “Typically, there’s some kind of optimisation between those three levers that we need to read. But in this instance, certainly the key driver was packaging and packaging as a function of that weight save,” explains Valentim.

A big part of what Conflux is able to achieve is due to the company’s understanding of the 3D printing process. “We are a thin wall specialist,” Valentim explains, adding that the greater the surface area is for cooling, the more effective the heat exchanger will be. In the case of a small device like the Donkervoort WCAC, a unit needs to have ultra-fine geometry.

Much of this was defined by the build accuracy of the 3D printers in Conflux’s range of EOS metals systems. Given Conflux’s work for EOS – developing custom heat exchangers for its multi-laser turnkey solutions arm, AMCM – it’s likely that these machines are as custom-tuned as Donkervoorts’s engines.

Typically, Conflux can deliver a gas tight wall a mere 300-microns wide and can create features as tiny as 150 micron-wide cooling fins.

Inside knowledge

Valentim hints that the end-to-end process leverages a number of unnamed softwares, but the industry recognition of tools like Catia and Ansys Fluent in the automotive space helps it build trust with clients.

The rest of the knowledge and tools that Conflux uses are a well-kept secret. The company only shares ‘the box’ with clients, “and not what’s inside,” states Valentim, explaining that the processes and technologies for designing optimised devices and developing fine geometries using AM production methods is so embryonic that protecting this IP – even from close clients – is key.

Once a design has been finalised, it goes into EOS Build for final build processing and smart monitoring. It is then built using AlSi10Mg aluminium alloy, before undergoing an extensive in-house post processing regime, which includes a surface coating to ensure longterm durability and add further corrosion resistance.

In this case, the solution delivered results so effective that Donkervoort’s team was able to downsize the package size even further from their original request, while Conflux’s design added other benefits including better serviceability for maintenance and easier piping from the turbo.

The end result is a pair of aluminium-alloy units weighing just 1.4kg each, compared to 16kg for conventional air-to-air units with similar thermal capacity.

This lightweight package of cutting edge engineering only adds to the expectations around the performance of the P24 RS when it is finally released. One thing’s for sure, though – it’ll be fast.

This article first appeared in DEVELOP3D Magazine

DEVELOP3D is a publication dedicated to product design + development, from concept to manufacture and the technologies behind it all.

To receive the physical publication or digital issue free, as well as exclusive news and offers, subscribe to DEVELOP3D Magazine here