The PiCycle is a new breed of electric bicycle. Designed and manufactured in California

When you see the PiCycle for the first time, you can’t help doing a double take.

With its arched aluminium tube it bears some resemblance to a bicycle, but not like one you’ve ever seen before.

In fact, it’s an electric bicycle offering pedal, motor or hybrid propulsion – a melding of the best of both a bicycle and motorcycle.

“I love that PiCycle elicits strong feelings including bad ones,” says PiMobility’s founder and CEO, Marcus Hays.

Hays set up PiMobility in Sausalito, California, in 2000. His aim was to create an electric hybrid bicycle that would be all about efficiency, not only of structure but also of purpose.

He felt frustrated that the only country where electric bicycles could be made cost effectively was China. He wanted to engineer a simpler structure that would achieve economies of scale without the need for cheap labour.

“My aim was to organise all of the otherwise disparate parts that comprise an electric bicycle and human powered propulsion into an integrated whole, eliminating plastic whenever possible and solving critical battery reliability issues,” explains Hays.

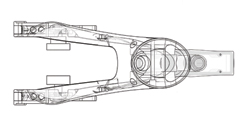

The question was: how would he efficiently connect two wheels with a motor, batteries and electronics? The most straightforward answer was inside the object itself. The arch ensued – a clear case of form following function.

Hays believed that this arch design would offer many benefits over conventional layouts. “The arch provides a number of opportunities to solve a long list of problems relating to electric hybrid bicycles that the double diamond simply can’t and wasn’t intended to,” he says.

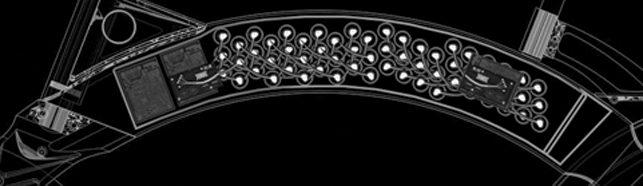

Most importantly the interior of the arch offers a great amount of unobstructed space. This meant that Hays could do away with the plastic battery enclosures that he has such a gripe with and, instead house the batteries securely inside the arch itself.

As well as providing strength, the arch also provides cooling and heat dissipation for this power source, with air moving through the arch and over the battery length as the bike is ridden.

The arc angel

Hays made his first rudimentary sketch of the arch-based PiCycle in Spring 2000. Although he says several prominent engineers tried to talk him out of the project early on, he relentlessly pursued.

From pencil sketches, he jumped directly to the real thing and commissioned a commercial building firm to roll a four-inch tube from an off-the-shelf extrusion. Although this process took six months, when he received the tube he knew that he was onto something special. “When I saw my first finished tube it was simply beautiful to gaze upon,” he proudly boasts.

Committed to the arch, he then worked on making the design simpler. This involved, amongst others, subtracting tubes, reducing the wheelbase, implementing a rubber belt drive and embedding WiFi diagnostics. But it was by no means a smooth development process as many obstacles and challenges arose.

Finding the right machine technology proved highly challenging, as did sourcing the appropriate tubes that weren’t dented or twisted.

“The lack of any straight edges also made for some mind-bending challenges during otherwise straightforward processes such as welding fixture construction,” recalls Hays.

Sustainability drive

Throughout the development Hays remained loyal to his vision of creating a truly sustainable transport solution. “Green design and manufacturing processes require deep commitment as the temptation when finances are being challenged is to round off the corners,” he explains.

“I encourage all to resist the temptation of implementing low cost, antiquated, and otherwise failed methodologies because the end product and experience for all concerned – including employees, customers and management – is so much better when the aim remains true.”

Sourcing the right sustainable material for the arch itself was a key consideration. Hays chose recycled aluminium, as it requires just one-thirteenth the amount of electricity to produce when compared to virgin aluminium, further reducing environmental impact. “After factoring in life cycle the evidence supports down-cycled aluminium being the cleanest possible material for motor vehicle platforms,” confirms Hays.

Although the current PiCycles are made from this material, he says that he will keep looking at new materials and will replace it if something better and more sustainable comes along.

Hays wants to utilise as many green manufacturing processes as possible and although the PiCycle has fewer welded intersections than a double diamond construction, his objective is to minimise the amount of welding necessary and possibly even replace it. He feels it’s rather time consuming and the objective is to make the PiCycle as efficient a structure as possible.

Hays has also carried out a life cycle assessment of the bike. “We estimate that a PiCycle frame offers a 50-year lifecycle,” he explains. “Combine this with the fact PiCycle is ‘battery agnostic’.

This means that the tube interior invites virtually any battery configuration or chemistry so when the time comes in roughly 15,000 miles to replace the batteries, PiCycle will not be outmoded by battery pack issues.”

The life of Pi

The PiCycle project has been many years in the making and has required a great deal of patience on Hays’ part. As he puts it, “Human power is a very fickle energy source.”

Apart from a lack of any outside funding, one of the main reasons for the slow development process is that with it being a completely new design, he had to invest a great deal of time in ensuring it was ergonomically sound. “Aligning PiCycle’s ergonomics perfectly with the rest of the machine required several generational evolutions (four to be exact),” he says.

However, the project was given a real boost when in 2009 PiMobility became an Autodesk Clean Tech Partner. This program supports emerging clean technology companies in North America and Europe by providing them with up to five licenses of Autodesk design and engineering software. “It was at this juncture I was able finally to integrate all of my ideas into a single CAD file,” says Hays.

“The Autodesk support also opened doors to engineers previously beyond my price range. This revolutionised Pi’s workflow and in 2010 we undertook what was literally an ‘axles-up’ redesign such that while the shape of PiCycle appears relatively unchanged for 2011, it is a completely new product,” he adds.

Hays and his team were able to use each of the Autodesk programs – Inventor, Vault, Alias, Showcase and Publisher – via Parallels desktop for Macs, which allows for Windows applications to be run on a Mac.

“As a latecomer to this technology my discovery that Inventor incorporated relatively intuitive tool sets with Mac compatibility to boot made what otherwise would have been an especially difficult technology transition into something much less difficult and in some cases even enjoyable,” comments Hays.

Whilst Inventor has been used for 3D modelling, Alias with its conceptual design tools and Showcase 3D visualisation software is turning out to be especially valuable for the website ‘configurator’ that the PiMobility team are currently erecting on picycle.com.

Autodesk Vault data management software is also proving to be very useful considering that PiMobility’s supply chain consists of some 36 individual suppliers scattered from Louisiana to China. “The intuitive quality of all the Autodesk software products we are using makes it possible for all our teams (engineering, design, communications, technical manual and writing teams) to integrate and interface very efficiently and economically,” says Hays.

Within just a couple of months of using Inventor, the team made some valuable discoveries. For instance, they realised that by simply increasing the tube diameter from 4 to 4.5 inches they could alter the design of the battery pack shaving $360,000 in cost over 1,000 units.

“This change not only impacted the battery pack for the better but relieved several areas where tolerances were especially tight including the phase-change based material that houses the battery and electronic components within the tube,” explains Hays.

“This alteration also made it possible to relocate the charger to the tube’s interior eliminating the need to lug external battery chargers around in a backpack or messenger bag.”

It wasn’t just the frame that was modelled in Inventor but all the components too. “We were having so much fun with the software Autodesk granted that we went mad modelling everything on our shelves – tyres too,” smiles Hays.

Although Inventor is a digital prototyping solution PiMobility still opted to make physical prototypes of the PiCycle. “With Inventor we no longer have to make prototypes but we do anyway,” says Hays. “Mostly because we’re a bunch of kids when it comes to riding anything new, which makes it impossible for anyone here to wait for production.”

Local support

Hays has tried to source components as locally as possible but with most bicycle parts made in China, Taiwan and Malaysia he can’t help having a global supply chain.

They do however source PiCycle’s down-cycled aluminium extrusions from mills located within a few hours of PiMobility’s headquarters.

This aluminium is then bent in-house with the use of a mandrel bender. “We have a machine that bends each tube in approximately 30 seconds,” explains Hays. “And because the fork is forged we can manufacture a PiCycle in approximately one hour.”

As a result of the less labour-intensive design and rapid manufacturing process the company is able to maintain production in-house and still be profitable. All fabrication and welding assembly is carried out in PiMobility’s 5,000 sq ft factory. “Quality is initially a priority over pure dollars and cents,” comments Hays. “We find that by doing most things internally we have more control over quality, resulting in happier customers and ultimately, we believe, more profit.”

Additionally, producing the PiCycles locally means that much of the transportation carbon that often affects even environmentally sustainable goods can be eliminated.

“We’re constantly tweaking our logistics to enhance fuel efficiencies but despite these various imperfections we estimate that every PiCycle embeds roughly 200lbs of carbon dioxide per vehicle during manufacturing,” admits Hays.

More than a decade on from his first sketch, the PiCycle is now in serial production. There are 1,000 units currently being manufactured and these will be available from April. One of these models will set you back $2,995.99 (£1,880).

“The price of a PiCycle is governed more by LiION battery costs than any other component and unfortunately it’s something we have little to no control of,” explains Hays.

“Battery development and scaling trends do however point to a near term horizon of significantly lower prices mated to significantly higher capacity. Savings that we will most certainly pass on to our customers as they occur,” he adds.

In his opinion, the PiCycle offers far more than conventional hybrid electric bicycles.

“Ride a PiCycle at 35mph down a San Francisco-grade slope and the differences are immediately apparent,” he comments. “From PiCycle’s braking spec to its steering geometry, wheelbase and balance, there’s no other electric bicycle I’ve ridden (yet) that instills an equivalent degree of confidence.”

So, ten years later and Hays is a happy man.

His journey may have been tough and painfully slow at times but in the end certainly worthwhile.

With the imminent launch of the 2011 model, there are many more designs in the pipeline. “Practicality without dullness is our mantra and in keeping with this philosophy we’re introducing a tandem. ‘PiCycle Too’ not only adds the benefit of a second pedalling position but it offers ergonomics compatible with an eight year old child.

“I know because I have an eight year old godson who has been assisting in PiCycle’s development since he was four. His assistance ranged early on in the form of child carriers then evolved into tag along bikes, trailers and now that he’s taller he wants to help pedal to school and back…the future is bright indeed.”

www.picycle.com

A new electric bicycle designed as a truly sustainable transport solution