With the 2024 acquisitions of Ansys and Altair, the simulation technology landscape is shifting again, says Laurence Marks. Mainstream CAD integration may have boosted useability at the sacrifice of true advancement, but there’s still plenty of creativity to be found in a new generation of simulation tools

Growth in simulation, in terms of sales volume – or more interestingly, in terms of models run per year – has in recent years defined the evolution of product engineering.

This growth has been far from uniform across different industry verticals and individual companies, in my opinion. It’s my hunch that much of the growth has come from big increases in spend and model creation at larger organisations, rather than further down the food chain. Either way, it means that the effects of the current market consolidation is felt differently by different groups of users.

It’s not the first time this has happened, although we saw a different picture in the twentieth century, as CAD companies acquired the then big CAE companies.

In the beginning, simulation companies were set up by individuals and small groups, and the customer base they served was similarly small technical groups. The links between CAD and simulation weren’t close, or particularly happy.

PTC went quickly into the game, buying Rasna in the 1990s. Dassault Systèmes purchased HKS and its Abaqus product. Siemens snapped up CD Adapco, LMS and others.

It wasn’t just the CAD companies that caught the acquisition bug. The larger simulation companies started buying smaller players, too, with Ansys buying Fluent and Ansoft, for example, thus widening its offer across physical domains as well as growing ever larger. These software groups eventually created a series of mainstream CAD-integrated products for the wider market, but migration from the CAD simulation space to more traditional simulation tools and activities has been patchy at best. And this evidence alone signposts where the market could be heading.

Limits of consolidation

The process of consolidation in the market has probably gone about as far as it can go now, with Ansys becoming part of Synopsys, Altair joining Siemens, and MSC being bought up by Hexagon a while back.

So, what will the simulation market look like in 2025? Well, one thing is sure: it will look nothing like it did in the 1980s and 1990s, when every new software release really did contain ‘significant enhancements’ and represented a significant move forwards in the art of the possible.

With consolidation, the pace of technical change has relaxed. Or, as the rate of technical change has relaxed, the pace of commercial consolidation has accelerated. I, for one, can’t tell which it is – although I guess both are probably inevitable and interlinked.

Today, we find ourselves in a world where simulation products are mass-market offerings, with customers and developers probably further apart from each other than they’ve ever been. Which is fine, if you want to apply slick integrated products to established

workflows.

If, like most people who work in simulation full-time, the motivation is applying creative simulation techniques to interesting problems and challenging physics, where do you look now? Because, at first glance, you might think that the options are distinctly limited.

While LinkedIn seems to have become a showcase for people who have copied and stolen other people’s work (OK, I mean my work), or who are prematurely showing off an as-yet unmarked student project (please don’t do that), it is still probably the best place to research and observe what could almost be described as a renaissance in the standalone simulation market.

Two distinct camps

The new developments seem to be split into two distinct camps. You want traditional FEA? PrePoMax leads the way and happens to be free. And there are others in the free space, including first-into-the-field Openfoam. I’m not sure that the availability of these products is as significant as some think. They are great for what you pay, but do they stack up in the commercial environment of their users? I’d say that this isn’t clear yet, but sticking my neck out, I would also say that they won’t be replacing paid-for products any time soon.

In the second camp, more critically for the future of simulation, there are many new ‘real’ products on the market. These generally don’t look like the traditional FEA and CFD products of the 1980s and 1990s, or even the mainstream products now sold by the megacorps.

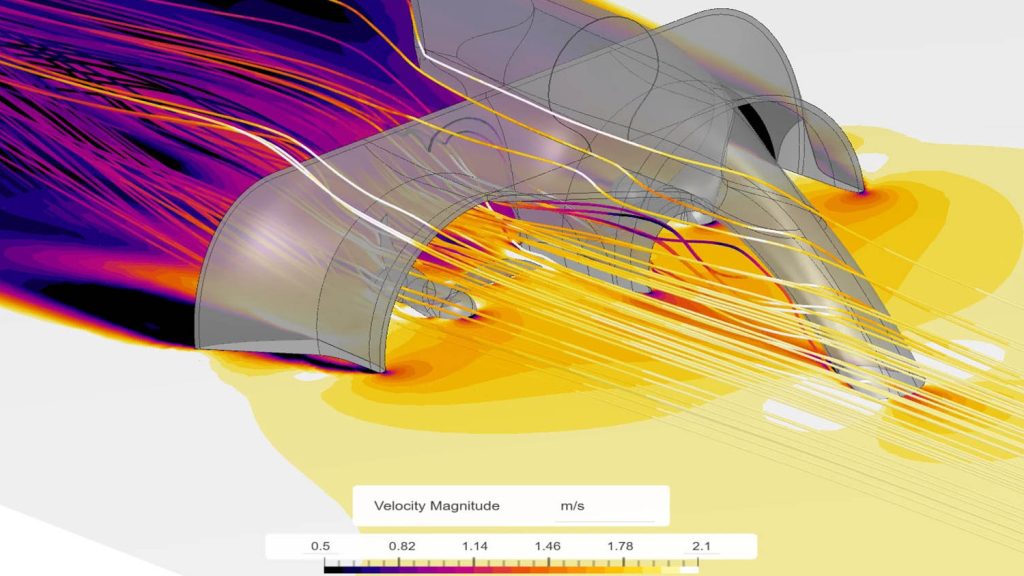

New CFD codes based in Lattice-Boltzmann Method (LBM) technologies, like Pacefish, and new particle-based codes like Dive and ParticleWorks, are carving a niche in the more specialist reaches of the CFD application space.

The hunt for new entrants into the market also uncovers an interesting point. You quickly become aware of the technologies and companies that you already knew existed, but which have kept a low profi le and haven’t yet become some minor division of any IT megacorp.

Here, I’m thinking of products like Converge CFD, which is both established and highly technically competent. There are still significant players in the sim space that haven’t joined the headlong charge into the corporate big time and which still seem to maintain a steady focus on technology.

AI outlook

This leads me on to the topic of what AI means in the simulation space. It’s too big a subject for here and now, largely because I think the CAE companies are sending out messages that could at the very least be called ‘mixed’. I’m not certain what I think the role of AI in simulation is going to be at this stage, but it’s pretty obvious that it isn’t faster CFD runs.

Presenting at the NAFEMS UK conference, I followed the PhysicsX team onstage, and from what I learnt, this is an organisation doing something truly creative using AI in the simulation space, and what’s more, it’s doing so outside of the usual CAE megalith organisation. That company is one to watch, I’d say.

So where does all this get us? Nothing ages as quickly as opinions about the future, but it looks to me like we’ll end up with two CAE streams: one that is integrated into mainstream CAD and CAE in a limited way; and another more fully integrated group. And by loosening the connection, we’ll end up with the rebirth of the ‘point solution’.

Technical products that solve a problem earn their keep by generating and enhancing IP without forming a key part of a slickly integrated whole. The big CAE vendors will still continue to supply the vast chunk of the simulation space, and they will do that effectively, with products that perform at levels we could not have dreamed of years ago. But small teams of simulation and physics specialists will continue to drive creativity, via a new generation of more focused applications.

The winners in this space look likely to be those people who can interact and optimise their work using tools like Python. So rather than mass extinction, we might in fact be looking at a new beginning, driven by consolidation in the wider market. Or perhaps not – but I certainly know which scenario I hope to see.

This article first appeared in DEVELOP3D Magazine

DEVELOP3D is a publication dedicated to product design + development, from concept to manufacture and the technologies behind it all.

To receive the physical publication or digital issue free, as well as exclusive news and offers, subscribe to DEVELOP3D Magazine here